Y-Chromosome: The Cryptic Male Guide to Human Genetics and Evolution

Y-Chromosome: The Cryptic Male Guide to Human Genetics and Evolution

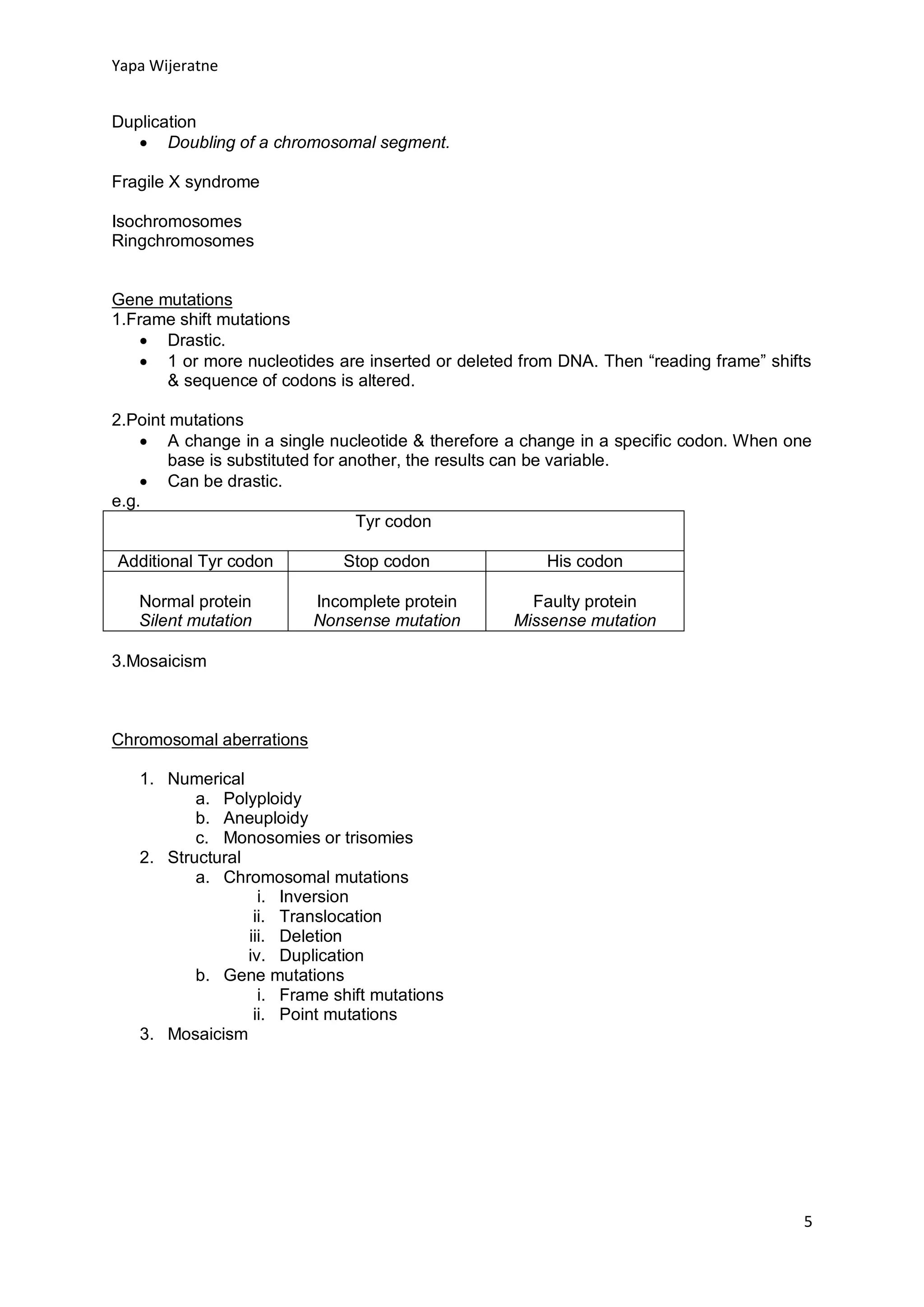

Beneath the complex architecture of the human genome lies a slender yet defining segment—the Y chromosome—responsible for male sex determination and deeply entwined with evolutionary biology, medical research, and human diversity. Though often overshadowed by its larger chromosomal partners, the Y chromosome plays a crucial role in developmental pathways, genetic stability, and the study of paternal lineages. Spanning approximately 59 million base pairs, this uniquely structured chromosome contains genes vital for spermatogenesis, hormone regulation, and sex differentiation, while harboring repetitive sequences and non-coding regions that challenge both scientists and laypersons alike.

From guiding embryonic development to serving as a genetic time capsule, the Y chromosome reveals layers of biological significance rooted in both function and history.

Y-Linked Traits and Their Biological Impact

The Y chromosome is the cornerstone of male-specific development, encoding key genes such as SRY (Sex-determining Region Y), which initiates testis formation in a genetically male embryo. Without this master switch, gonadal development defaults toward ovarian pathways, underscoring the chromosome’s irreplaceable role in sexual differentiation. Beyond SRY, the Y holds genes instrumental in sperm production, including DAZ (Deleted in Azoospermia) alleles critical for meiosis and fertility.

These genetic elements highlight why Y chromosome analysis remains pivotal in reproductive medicine and genetic counseling. Y-Associated Disorders and Clinical Relevance Despite its streamlined architecture—composed of mere two large pseudoautosomal regions—mutations or structural rearrangements on the Y chromosome link to a spectrum of clinical conditions. Syndromes such as Y chromosome microdeletion disorders, particularly those affecting the AZF (Azoospermia Factor) regions on Yq microdensities, frequently lead to infertility and hypogonadism.

A deletion in AZFa can impair sperm count, while AZFc losses often result in oligozoospermia, yet some variants remain asymptomatic—illustrating variability in penetrance. Additionally, recent studies implicate Y chromosome copy number variations in neurodevelopmental differences, though causal links remain under investigation. “The Y chromosome’s role in male health extends far beyond fertility—it influences systemic physiological balance,” notes Dr.

Elena Atkins, a genetics researcher at the Human Genome Institute.

Y-Linked Y-Chromosomes and the Tracing of Human Ancestry

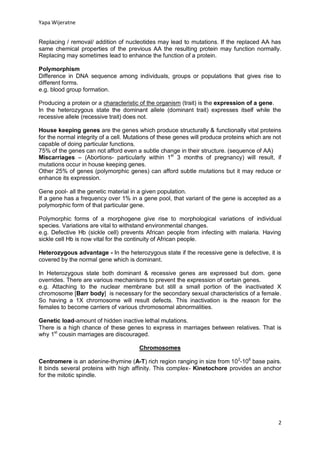

The Y chromosome serves as a molecular record of paternal lineage, passed nearly intact through generations. Due to minimal recombination—except at the pseudoautosomal regions—Y chromosomes accumulate subtle mutations over centuries, forming unique haplogroups that map ancient human migrations.

These genetic lineages allow scientists to reconstruct prehistory, identifying key demographic shifts such as the Out-of-Africa exodus and subsequent peopling of Eurasia, the Americas, and Oceania. Forensic and anthropological laboratories routinely employ Y chromosome short tandem repeats (Y-STRs) to trace family trees, resolve paternity disputes, and study indigenous populations’ genetic continuity. In some African tribes, deep Y-chromosomal lineages extend back over 200,000 years, making it a living archive of evolutionary resilience.

Y-Structure: From Macro to Micro – A Chromosome of Extremes

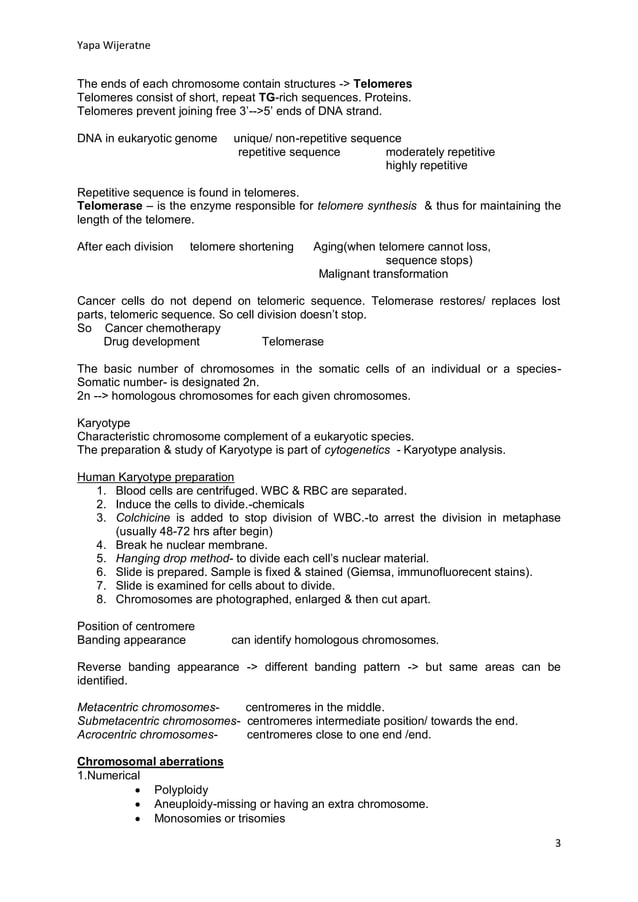

The Y chromosome’s physical architecture is a paradox: it is both compact and complex.

While drastically smaller than autosomes—approximately 20–30 Mb compared to ~150–250 Mb in autosomes—it defies simplicity through its unique organization. The chromosome is divided into distinct regions: the male-specific region (MSY) contains ampliconic sequences rich in palindromic DNA and repetitive elements, essential for gene dosage compensation and DNA repair. This region includes gene clusters like RSPY, involved in centromere stability, and numerous sperm-specific proteins.

In contrast, the azítě regions (AZFa, AZFb, AZFc) are prone to deletions linked with infertility. This streaming structure enables dynamic recombination during spermatogenesis, yet also increases vulnerability to rearrangements that contribute to disease. The Y’s compact size belies its genetic richness, shaped by evolutionary pressures favoring stability amid replication challenges.

Y and Gene Dosage: Compensation Without Recombination

A defining feature of the Y chromosome is its limited recombination with the X, limited primarily to pseudoautosomal segments.

This restriction drives evolutionary erosion: without regular crossover, deleterious mutations accumulate in non-recombining regions, leading to what biologists term “Muller’s ratchet”—a gradual unloading of harmful variants through generational selection. To counterbalance this loss, the Y has retained specialized gene families focused on male fertility and dosage-sensitive functions. For instance, multi-copy genes within ampliconic blocks enable “relative dosage compensation”—a redundancy that buffers against haploinsufficiency.

“The Y chromosome has evolved molecular mechanisms to preserve critical gene dosage despite recombination constraints,” explains Dr. Marcus Lin, a chromosomal biologist at Stanford University. This adaptive architecture underscores nature’s ability to stabilize essential functions under evolutionary pressure.

Y-Restricted Genetic Diversity and Evolutionary Insights

Compared to autosomes, the Y chromosome exhibits significantly lower genetic diversity across human populations.

This bottleneck effect stems from its paternal mode of inheritance, where only half the genome is transmitted per generation, combined with strong selective pressures on fertility-related genes. Yet within this constrained landscape, variation thrives—particularly in regulatory and non-coding segments. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and structural variants in Y-STRs serve as genetic fingerprints, enabling granular analysis of population structure and migration patterns.

For example, Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b dominates in Western Europe, offering clues to Bronze Age Indo-European expansions. Meanwhile, minimal diversity also highlights vulnerability—genetic disorders linked to Y chromosome microdeletions affect ~1 in 100¿¿??0¿¿??0¿¿?? men globally, emphasizing the need for continued surveillance and intervention.

The Future of Y-Chromosome Research: From Fertility to Forensics

Advances in sequencing technology are transforming Y chromosome studies, revealing previously hidden complexity.

Long-read sequencing now resolves repetitive regions once deemed “unsequencable,” uncovering novel genes and regulatory networks. Single-cell analyses are mapping Y chromosome behavior during gametogenesis, shedding light on male infertility mechanisms. In medicine, CRISPR-based tools are being tested to repair pathogenic Y chromosome mutations, offering hope for treating_Y-linked infertility in the future.

Forensics continues to leverage Y STR profiles in audience-des nail-the-teasejoint crime investigations, partly due to its persistence in degraded samples and paternal lineage specificity. Furthermore, comparative genomics across mammals reveals conserved Y-chromosome functions, informing evolutionary medicine and genetic resilience research. As understanding deepens, the Y chromosome ceases to be a genomic afterthought and emerges as a central player in human biology and medicine.

The Y chromosome, though diminutive in size, holds enormous significance across genetics, medicine, and anthropology.

Its roles in sex determination, fertility, evolution, and ancestry mapping illustrate the intricate interplay between structure and function. Far

Related Post

Unlocking the Metaverse: The Definitive Guide to How to Create A Hit Roblox Game

Analyzing the Enduring Legacy and Professional Trajectory of Kellie Shanygne Williams

Here Is The Real Meaning Behind Erome Website 9

Unveiling the Meaning Behind On a Steel Horse I Ride