Where Tectonic Giants Collide: The Landscapes and Risks of Continental Continental Convergent Plate Boundaries

Where Tectonic Giants Collide: The Landscapes and Risks of Continental Continental Convergent Plate Boundaries

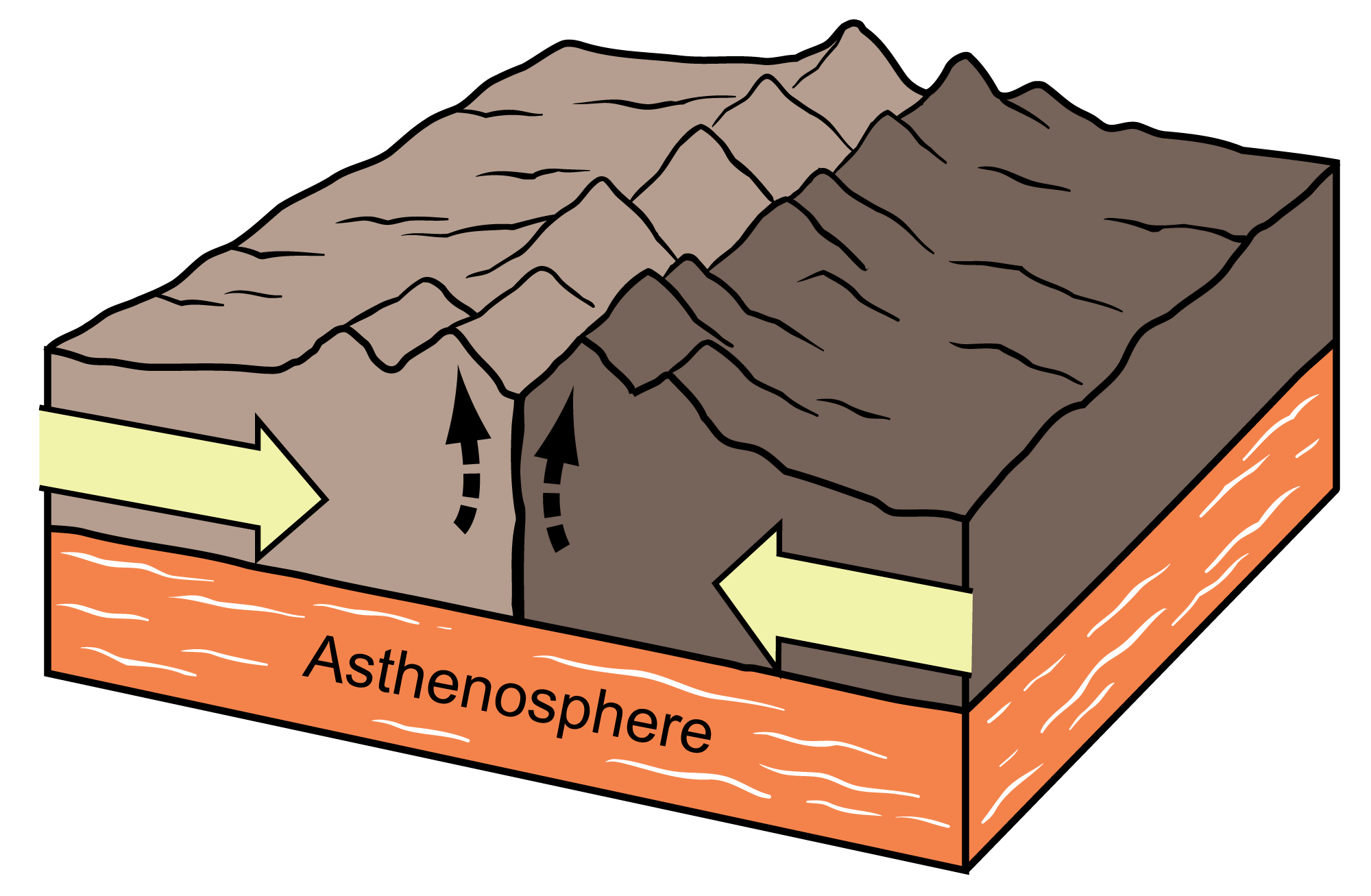

emerging at the heart of Earth’s dynamic geology, continental continental convergent plate boundaries represent some of the most powerful and transformative forces shaping the planet’s surface. Unlike oceanic-continental or oceanic-oceanic convergence, where one plate slips beneath another, continental-continental convergence occurs when two massive landmasses collide, resisting subduction and instead forcing crustal thickening, mountain building, and seismic upheaval. This colossal interaction drives the creation of vast mountain ranges and alters climate patterns, while posing significant hazards to millions living near these unstable zones.

These boundaries are not just geological features—they are engines of Earth’s ever-evolving structure, bearing witness to millions of years of crustal drama. The mechanics of continental collision begin when tectonic plates driven by mantle convection converge, deafeningly slow yet relentless in their movement—often just centimeters per year. As the continents meet, neither plate yields easily; instead, their rigid crust compresses, folds, and fractures.

This resistance triggers intense crustal shortening, uplift, and deep-seated deformation, all hallmarks of orogenic (mountain-building) processes. “The Himalayas are the ultimate testament to this process,” notes Dr. Elena Marquez, a structural geologist at the University of Geneva.

“Formed by the collision of India and Eurasia, this mountainous spine rose incrementally over tens of millions of years, driven by forces deep within the lithosphere.” This slow but unyielding collision creates some of the highest and most geologically active terrain on Earth. Characteristics of continental-continental convergent boundaries are distinct and marked by dramatic surface expressions. Unlike subduction zones, no oceanic trench forms—what remains is a zone of intense deformation, thickened crust, and widespread metamorphism.

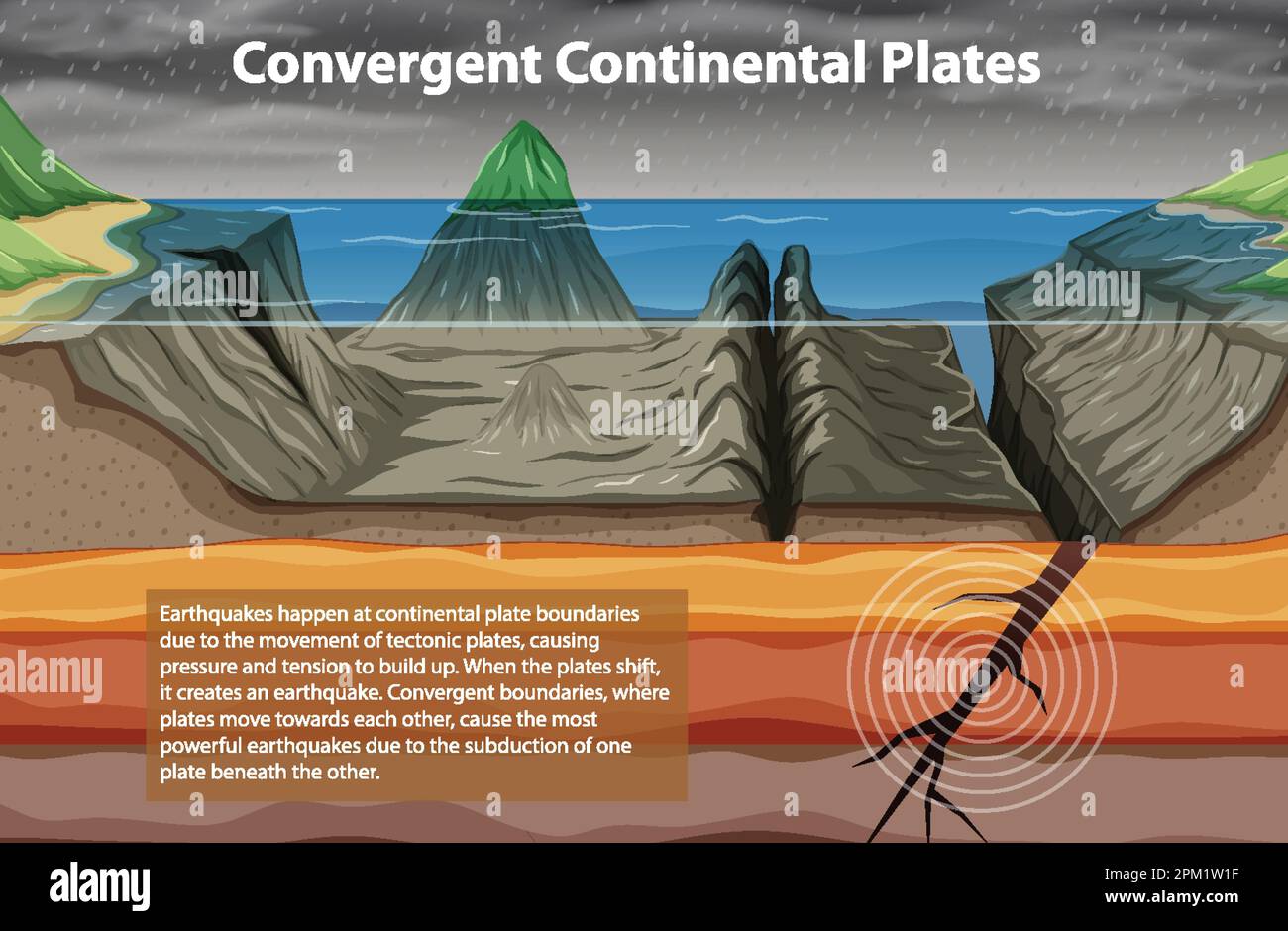

The crust beneath these boundaries can grow hundreds of kilometers thick, far exceeding natural limits, and is frequently marked by high-grade metamorphic rocks and deep-seated fault systems. Seismic activity is common but varies: shallow, powerful earthquakes rupture near the surface, while deeper quakes reflect ongoing stress in the subducted or deeply buried crust. geographically, several key zones exemplify these powerful interactions.

The Himalayan-Tibetan orogen stands as the most prominent, formed by the northward drift of the Indian plate crashing into Eurasia. Stretching over 2,400 kilometers, it includes the Himalayas—the world’s tallest range—and the Tibetan Plateau, the planet’s largest and highest elevated region. This area remains seismically active, with devastating quakes like the 2015 Nepal earthquake underscoring the ongoing threat.

Another major zone lies along the southern margin of Eurasia, particularly in the Alpide Belt, where the African plate converges with Eurasia, creating the Alps, the Hindu Kush, and the Zagros Mountains. Here, the collision of Africa with southern Europe has sculpted some of Europe’s most iconic peak systems through complex folding and thrust faulting. At the core of continental-continental convergence is crustal thickening—a process that reshapes the lithosphere over geologic time. As two continental masses collide, their roots bury deeper into the mantle, displacing dense mantle material and elevating the crust through isostatic rebound. This thickening generates immense uplift, capable of raising mountains several kilometers high within tens of millions of years—a pace imperceptible in human terms but profound in geological epochs. Crustal deformation occurs across a network of thrust faults, where slices of crust are pushed over one another, stacking rock layers like tectonic puzzle pieces. This process, known as nappe formation, creates layered mountain belts with complex internal structures. Metamorphic transformations also occur under intense pressure and heat, converting sedimentary and igneous rocks into schists, gneisses, and migmatites—fragile yet resilient signatures of deep crustal activity. The energy released during these collusions is immense. The Indian-Eurasian collision, continuing to this day, thickens crust by up to 70 kilometers beneath the Himalayas, increasing elevation at an average rate of 5 millimeters per year. “Each year, the Himalayas grow a fraction—but the total over millions of years is staggering,” explains Dr. Marquez. “This is not just building mountains; it’s rewriting the Earth’s surface weather and climate systems.” This crustal thickening feeds volcanic activity in peripheral regions, though unlike subduction zones, it rarely produces explosive volcanism directly within the collision zone. Instead, magmatism often migrates toward the plate margins or complicates the base of the mountain belts, adding further complexity to the geologic picture. Despite the absence of oceanic trenches, continental-continental convergent boundaries pose serious seismic threats. While earthquakes here are typically less frequent than in subduction zones, they can be profoundly destructive due to shallow focus and proximity to populated areas. The locked crust along these zones accumulates elastic strain over centuries, releasing suddenly in events that rupture wide zones. “Many of these systems host ‘silent earthquakes’—slow slip events that build stress without triggering major surface shocks,” notes Dr. Marquez. “This creates a deceptive sense of stability, lulling communities into underestimating their earthquake risk.” Recent studies using GPS and satellite radar interferometry reveal ongoing crustal deformation across these belts, highlighting active fault segments still storing energy. The 2015 Nepal quake, a devastating M7.8 event, exemplified how hidden thrust faults promise sudden release. Its rupture extended over 100 kilometers along the Main Himalayan Thrust, triggering landslides and valley-wide devastation. Moreover, the thickened crust itself contributes to subsidence in adjacent basins, creating foreland fold-and-thrust belts that trap sediments and influence river systems. This interplay fuels long-term geomorphic evolution, demonstrating the profound interconnectedness of tectonic forces. Continental-continental convergent zones birth some of Earth’s most spectacular landscapes. The Himalayas rise to extremes, housing Everest and K2 while encompassing diverse ecosystems—from subtropical foothills to alpine tundras. The Tibetan Plateau, elevated to over 4,500 meters, functions as both a climatic driver and a geological icon, altering atmospheric circulation and intensifying Asian monsoons. The geomorphic signature of theseThe Process of Crustal Thickening and Mountain Building

Seismic Risks and Hidden Hazards Beneath the Surface

Landscapes Shaped by Collision: From Peaks to Plateaus

Related Post

Ashleigh Merchant Unlocks Agriculture’s Future: How Precision Farming Is Revolutionizing Sustainable Food Production

Jeff Hardy Making New Willow Mask For Possible WWE Debut

Unveiling The Mystery: Rick Ness’s Transformed Nose

Pedal the Wild: Explore the Grand Teton Bike Path from Jackson to Moose with One Unmatched Trail Experience