When Did the Fall of Banten Really Collapse? Unraveling the Sultanate’s Final Days

When Did the Fall of Banten Really Collapse? Unraveling the Sultanate’s Final Days

When the curtain fell on the once-mighty Sultanate of Banten, the endgame of a centuries-old Javanese power unfolded through a confluence of internal fractures and external pressures. The question “When did the Sultanate collapse?” reveals a complex timeline anchored in political betrayal, shifting trade dynamics, and the relentless expansion of Dutch colonial forces. Far from a sudden downfall, the collapse of Banten unfolded over several decades, marked by key turning points that eroded its autonomy and sovereignty.

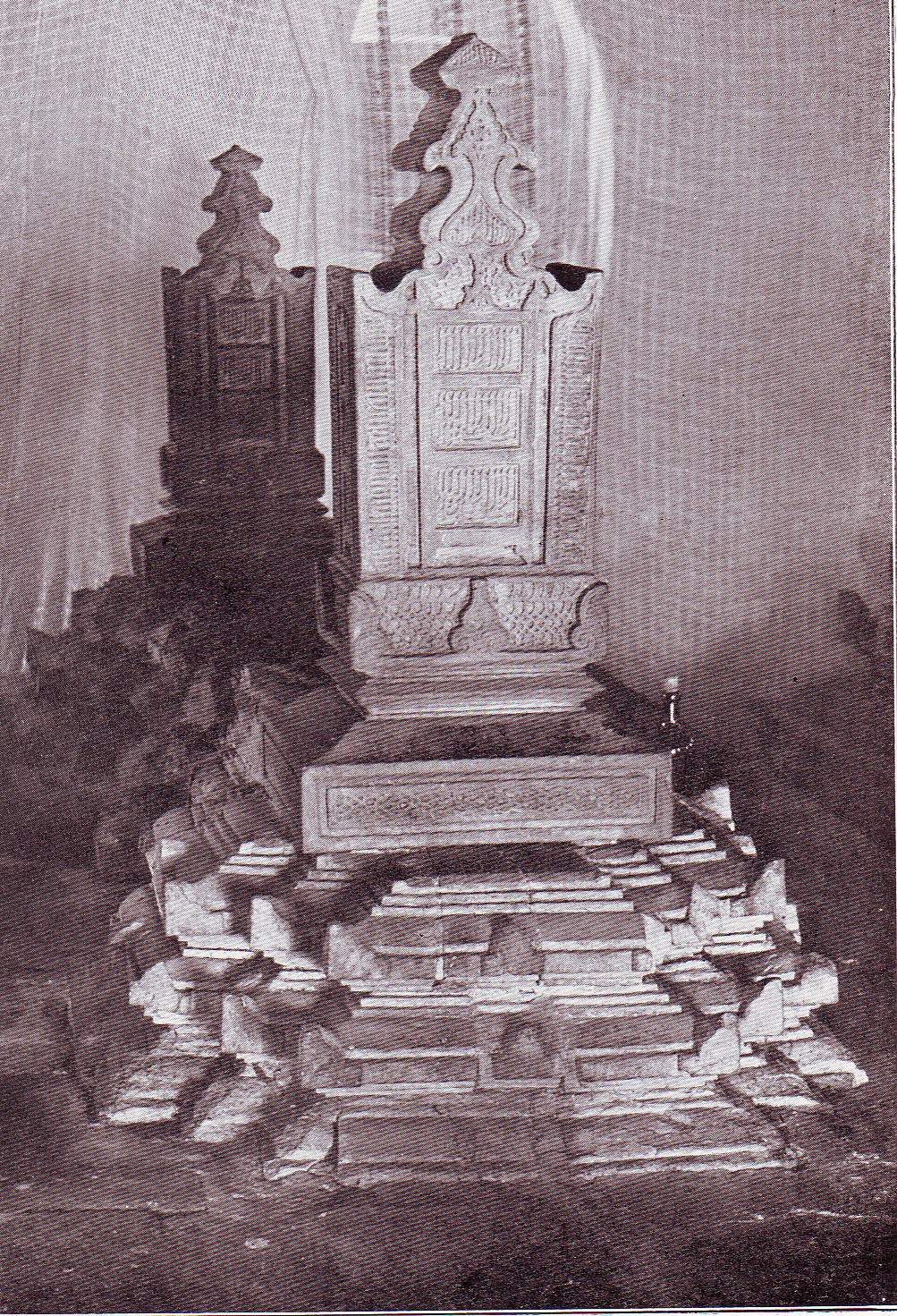

By examining these stages, one uncovers not just a date, but a nuanced trajectory of decline rooted in both structural weakness and acute crises. The formal disintegration of the Sultanate is generally pinpointed to 1813, but its dissolution began much earlier, revealing layers of vulnerability that had long been ignored. Banten, once a dominant maritime polity controlling vital trade routes in western Java, had enjoyed golden ages in the 16th and 17th centuries, flourishing as a center of spice and textile commerce.

However, by the early 18th century, diminished royal authority and rising rivalries set the stage for instability. Internal discord—particularly succession disputes and factionalism within the ruling elite—fractured unity at a critical time. A 1699 civil war, triggered by a contested succession, fatally weakened central power, leaving the sultanate exposed to both internal dissent and foreign encroachment.

External pressures intensified throughout the 1700s, with the Dutch East India Company (VOC) relentlessly expanding control over Java’s western coast. The VOC exploited Banten’s growing instability by forging alliances with regional rivals and securing exclusive trade concessions—a strategy that gradually eroded Banten’s economic base. By the late 1700s, Dutch military incursions and political manipulation increasingly undermined the sultan’s ability to govern.

The sultanate’s last vestiges of autonomy were crushed when, in 1813, British intermediaries backed by Dutch forces ousted the ruling sultan, formally abolishing the independent state. This marked not a sudden collapse, but the culmination of decades of cumulative decline. Understanding the exact “when” requires acknowledging both immediate and systemic factors.

While 1813 is the traditional endpoint, scholars emphasize that the sultanate’s functional collapse occurred earlier—perhaps as early as the 1750s, when royal authority faded and Dutch influence became inescapable. Political fragmentation, loss of trade supremacy, and military defeats cumulatively hollowed out Banten’s independence long before formal instruments of dissolution were signed. The fall ended an era defined by regional autonomy and cultural pride.

The collapse was less a single moment and more a gradual erosion punctuated by decisive losses. Historical records stress that the Sultanate of Banten began its irreversible decline not with a battlefield defeat, but with the fracturing of its internal cohesion—a cautionary tale of how even powerful states can unravel when governance falters and external forces tighten their grip. In the end, the story of Banten’s fall is not merely one of dates and treaties, but of a society caught between tradition and transformation.

Its collapse underscores the fragility of political power amid shifting economic and military realities, leaving behind a legacy that continues to shape Java’s historical memory and identity.

Internal Fractures: Succession Wars and Royal Infighting

Built on shaky dynastic foundations, the Sultanate of Banten faced mounting internal challenges that undermined its resilience from within. The most immediate catalyst for decline was the spiraling instability following contested successions.The traditional principle of hereditary rule, while intended to preserve continuity, instead became a hotbed of conflict. After the death of Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa in 1683, a succession crisis erupted, igniting a nine-year civil war that pitted rival royal claimants against one another. Though the sultan ultimately triumphed, the damage was done—legitimacy was weakened, and noble factions carved out power bases that would later resist centralized control.

This pattern repeated across subsequent reigns. Weak or young rulers often provoked disputes among powerful princes and court factions, diverting attention from state affairs and sapping unified governance. By the early 18th century, the sultanate’s ruling elite had splintered into competing interest groups, each vying for influence.

The erosion of trust within the royal court meant that unified responses to external threats—such as rising Dutch interventions—became increasingly improbable. As historian Wisigneur R. Surya put it: *"The internal battles over succession turned Banten’s political heart from a strong engine into a fractured machine—each rival pushing its own agenda, weakening the state from within."* These internal rifts constrained military mobilization and economic reforms, leaving the sultanate fragmented and vulnerable when worsening external pressures mounted.

Economic Decline: From Trade Mastery to Economic Subjugation

Banten’s wealth had long flowed from its strategic position controlling critical spice and textile routes across the Strait of Sunda. For centuries, the port served as a key entrepôt linking Java with global markets, enriching the sultanate and financing its administration and military. Yet by the 17th century, this economic advantage began to erode.The rise of Dutch naval dominance disrupted traditional trade networks, while Banten’s inability to adapt to changing commerce patterns left it increasingly marginalized. The shift in global trade dynamics—from regional Javanese networks to increasingly direct Dutch maritime monopolies—deprived Banten of its revenue base. Dutch interlopers negotiated exclusive trading rights with compliant local leaders, bypassing Banten’s merchants and siphoning wealth to the VOC’s coffers.

This economic marginalization weakened royal coffers, limiting investment in infrastructure, defense, and administration. Moreover, Dutch pressure escalated with the 1660s–1800s, as they imposed tribute demands and favorable trade policies that further hollowed out Banten’s economic sovereignty. Even when nominally independent, the sultanate existed in a precarious ripple of Dutch control, dependent on foreign approval for legitimacy.

As one colonial-era document put it, *"Banten’s riches once fueled its power; by the late 1700s, those same riches funded its subjugation."*

External Pressures: The Dutch Conquest and Colonial Domination

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) and its successor states played a decisive role in Banten’s collapse, applying sustained military, political, and economic pressure from the late 17th century onward. Through calculated diplomacy, territorial seizures, and repeated military campaigns, Dutch forces progressively eroded Banten’s sovereignty, culminating in formal annexation by 1813. The VOC exploited Banten’s internal divisions early, forging alliances with rival princes and coastal communities eager to weaken the sultan’s hold.The 1699 civil war marked a turning point—Dutch support for certain factions ensured the sultanate’s inability to reassert unity even after military consolidation. This pattern repeated with increasing intensity over the 18th century: Dutch forces imposed unequal treaties, captured strategic ports such as Serang and Pangkalan Dua, and installed compliant administrators to manage local affairs. By the early 19th century, Banten was effectively a Client State, stripped of autonomous decision-making and increasingly dependent on Dutch military and financial support.

When events in 1813 unfolded—a coordinated invasion backed by British forces and local collaborators—the sultanate lacked the military strength or legitimacy to resist. Instead of a heroic last stand, Banten’s collapse unfolded as a predictable culmination of decades under Dutch suzerainty. The official end date thus reflects not only a military takeover but the systematic dismantling of self-governance.

Timing the Collapse: 1750s–1813—a Phased Decline

Whilst the definitive fall occurred in 1813, scholarly consensus identifies a gradual disintegration stretching from the mid-18th century to the early 19th century as the true trajectory of Banten’s collapse. The 1750s marked a critical inflection point: internal succession crises, combined with early Dutch encroachments, began dismantling royal authority. By the 1770s, economic subordination deepened as trade monopolies tightened, and foreign interference grew more overt.In the early 1800s, weak sultans struggled to command loyalty amid rising fractures, and the outbreak of the Anglo-Dutch wars in the region amplified pressure on Banten’s failing state. By 1813, the formal abolition of the sultanate was less a sudden event than a decisive coronation of decline

Related Post

The Evolution and Impact of News In Gujarati Language

California I-485 Processing Times: What You Need To Know

Bumpy Johnson: The Kingpin Who Redefined Organized Crime in Post-War America