What Is a Base? Unlocking the Foundation of Chemistry and Geology

What Is a Base? Unlocking the Foundation of Chemistry and Geology

A base is far more than a classroom formula—it is a foundational concept woven into the fabric of chemistry, geology, and everyday life. At its core, a base is a substance that donates hydroxide ions (OH⁻) in aqueous solutions or accepts protons (H⁺) in acid-base chemistry, but its significance extends beyond laboratory definitions. In nature, bases shape soil fertility, regulate pH in natural waters, and drive critical industrial processes.

Recognizing what qualifies as a base—and how it functions—unlocks vital insights into both molecular behavior and macroscopic phenomena.

Chemical definitions of a base begin with the Brønsted-Lowry model, which describes bases as proton acceptors. When ammonia (NH₃) reacts with water, it accepts a proton to form ammonium (NH₄⁺) and hydroxide ions: NH₃ + H₂O ⇌ NH₄⁺ + OH⁻ This ability to accept protons underpins how bases neutralize acids, raise pH levels, and participate in buffering systems essential for biological function.

Equally important is the Lewis definition, which expands the concept beyond protons: a base is any species that donates an electron pair. A classic example is sodium hydroxide (NaOH), which, when dissolved, releases hydroxide ions to react with acids, while metal ions like magnesium (Mg²⁺) in water act as Lewis bases by donating electron pairs to stabilize surrounding molecules.

Beyond theory, bases are categorized by strength—strong and weak—based on their tendency to fully or partially dissociate in solution.

- Strong basesWeak bases Because they do not fully ionize, their effects are more subtle, influencing enzyme activity in biology and environmental chemistry in slower, more controlled ways. The role of bases extends deep into geology, where they shape Earth’s surface and subsurface processes. Weathering reactions—critical to soil formation—often involve base-driven dissolution. For instance, when carbon dioxide (dissolved in rainwater) forms weak carbonic acid, it reacts with calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) in limestone, generating calcium ions, bicarbonate, and CO₂ gas: CO₂ + H₂O + CaCO₃ → Ca(HCO₃)₂ Here, weak bases like bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) act as byproducts, driving long-term changes in rock composition and contributing to karst landscape development—caves, sinkholes, and limestone pavements. Soil science further highlights bases’ ecological importance. Soil pH, dictated in part by base content, influences nutrient availability. Alkaline soils rich in base compounds (calcium carbonate, magnesium hydroxide) support specific crops, while acidic soils may require lime treatment—calcium oxide (CaO) or calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂)—to raise pH and boost plant uptake of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Indirectly, bases underpin countless industrial and technological advances. In water treatment, chemically processed bases neutralize acidic waste, preventing environmental damage while adjusting pH for safe reuse. In manufacturing, bases act as catalysts in soap synthesis (saponification), where triglycerides react with NaOH to form glycerol and fatty acid salts—molecular transformation driven by base chemistry. In biological systems, bases are indispensable. Enzyme function relies heavily on precise pH, regulated largely by base buffers like bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) in blood. The bicarbonate buffer system—H₂CO₃ ⇌ HCO₃⁻ + H⁺—maintains blood pH within a narrow, life-sustaining range of 7.35–7.45. Without this delicate acid-base equilibrium, metabolic processes would collapse, underscoring bases’ role as silent life maintainers. Beyond nature and biology, bases are pivotal in modern materials and energy. Ceramic glazes achieve their signature smoothness and brightness through base oxides like silica (SiO₂) and alumina (Al₂O₃), whose ionic and covalent bonding defines performance. In battery technology, alkaline batteries—powering devices from flashlights to digital cameras—use potassium hydroxide (KOH) as the electrolyte, enabling efficient ion transfer and sustained energy output. Emerging technologies, such as solid-state electrolytes and advanced fuel cells, continue to adopt base-based chemistries for improved conductivity and stability, demonstrating how foundational concepts evolve into cutting-edge innovation. Understanding what qualifies as a base—beyond mere hydroxide release—reveals a unifying principle across scales: bases stabilize environments, accelerate reactions, and sustain life. From dissolving in water to sculpting continents and regulating biology, their influence is both immediate and profound. As science deepens its grasp of base chemistry, so too does humanity’s capacity to harness these forces—engineered solutions for clean water, efficient manufacturing, and resilient infrastructure. A base is not merely a chemical category; it is a cornerstone of stability, transformation, and progress.

Related Post

Analyzing the Journey of Fofo Marquez: The Exhaustive Survey

Why WWE Evolution Had Such A ScaledDown Set

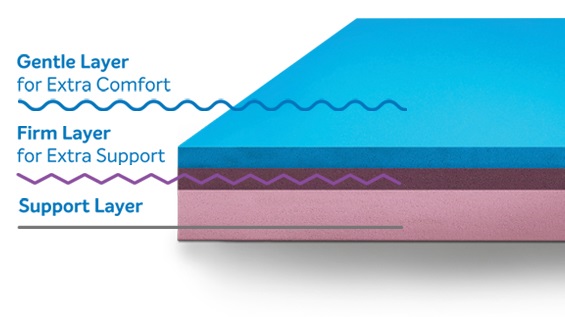

Sleepwell vs. Sleep Well: Which Mattress Dominates in 2024?