What Does Prohibition Mean—and Why It Still Shapes History and Society

What Does Prohibition Mean—and Why It Still Shapes History and Society

Prohibition is more than a historical footnote—it represents a deliberate societal experiment to ban alcohol, reshaping laws, cultures, and economies. At its core, “What Does Prohibition Mean?” refers to the legal restrictions imposed on the manufacture, sale, and distribution of alcoholic beverages, typically at the national or state level. From its most famous era in the United States during the 1920s to modern-day bans in Middle Eastern nations, prohibition reflects deep tensions between morality, public health, governance, and individual freedom.

Defining Prohibition: Legal Restriction of Alcohol Prohibition denotes a formal, government-enforced ban on alcohol. Historically, it emerged from social movements advocating temperance, often rooted in religious morality or fear of societal decay. When the U.S.

enacted nationwide Prohibition via the 18th Amendment (1920–1933), it criminalized liquor production and trade, enforced by the Volstead Act. This weren’t organic war on alcohol but a legislative overhaul: “The manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors” became illegal, violating personal autonomy while promoting public welfare. Similar policies today remain in countries like Saudi Arabia and parts of Iran, where religious doctrine informs law.

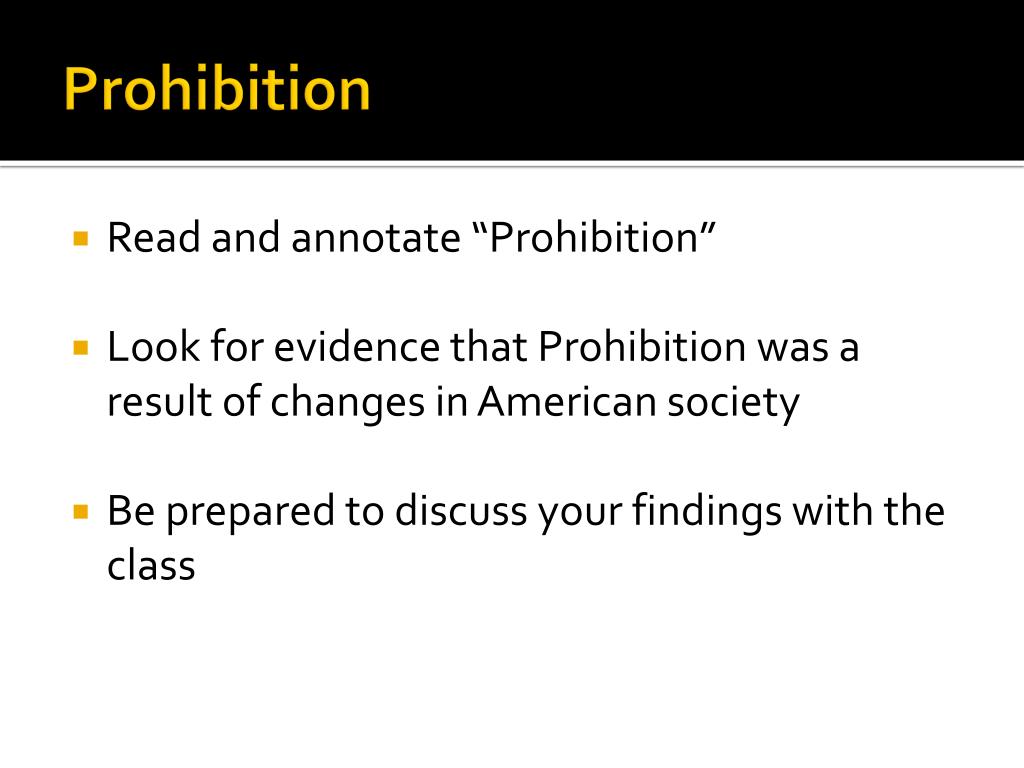

The Societal Catalysts Behind Prohibition Movements The push for Prohibition was fueled by multiple forces converging in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Urbanization and industrialization disrupted traditional community structures, amplifying fears that alcohol bred poverty, domestic violence, and crime. The temperance movement, led by groups like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, argued that banning alcohol would uplift families and communities.

As historian W.J.R. Allen noted, “Prohibition was as much about social control as it was about morality—targeting immigrants, urban ethnics, and working-class life.” Religious convictions also played a role, with many Protestant denominations viewing alcohol as a corrupting force incompatible with godly living. These alliances of reformers, women’s rights advocates, and moral crusaders turned local bans into national laws.

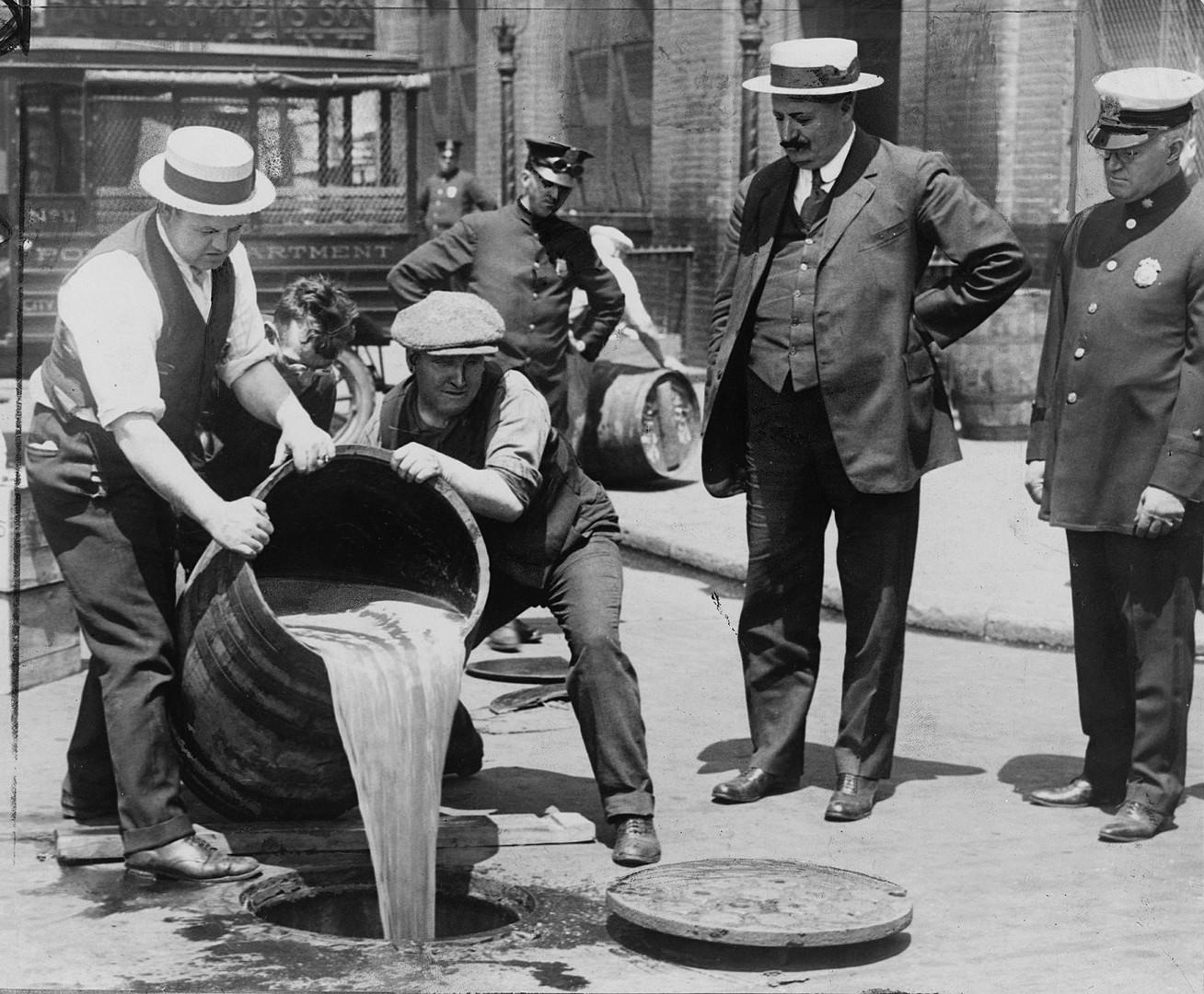

Unintended Consequences: The Rise of Illegal Markets Rather than curbing alcohol use, Prohibition often ignited widespread defiance. With legal supply abruptly cut, a vast black market flourished, controlled by organized crime syndicates adept at smuggling and production. The 1920s in the U.S.

exemplify this paradox: while supporters hoped a dry nation would emerge, gangsters like Al Capone built empires making and selling bootleg liquor worth millions. As historian David Farber observes, “Prohibition turned alcohol into a commodity more dangerous than ever, feeding corruption, violence, and public distrust.” Speakeasies—illicit bars hidden behind ordinary facades—became cultural hubs, blurring class and ethnic lines while fostering widespread disregard for the law. Far from eliminating alcohol, Prohibition reshaped it into a symbol of rebellion, forever changing public attitudes.

Economic Fallout and Fiscal Crisis The financial toll of Prohibition was staggering. Governments lost billions in tax revenue from legal alcohol sales—a critical blow during the Great Depression, when federal funds were desperately needed. Tax revenues from beer, wine, and spirits had once supported schools, infrastructure, and public services.

With Prohibition, local economies dependent on breweries, vineyards, and saloons collapsed, exacerbating unemployment. Moreover, law enforcement resources—constantly stretched thin—struggled to police widespread violations, leading to wasteful spending with minimal results. The economic paradox is clear: by banning alcohol, states not only lost income but also empowered criminal networks that drained broader society.

The Repeal Experiment: Unintended Lessons in Policy Failure The reversal came swiftly with the 21st Amendment (1933), the only U.S. constitutional amendment repealing a constitutional ban. Public sentiment shifted as Prohibition’s failure grew undeniable: crime surged, trust in government eroded, and the black market thrived.

Repeal restored regulated legal alcohol trade, generating new tax income—some $300 million in its first year—funding recovery efforts in the Depression era. Economists and policymakers noted a key lesson: banning deeply embedded behaviors rarely succeeds without parallel social consensus and enforcement capacity. As the reversal proved, Prohibition’s legacy is not merely historical but cautionary—one that informs modern debates over drug policy, censorship, and state control.

Modern Prohibition: Global and Regional Variations Though the U.S. repealed national Prohibition, restrictions on alcohol persist globally. In nations like Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Brunei, alcohol remains banned under religious or legal codes, enforced through strict penalties.

Even in liberal democracies, limited Prohibition persists: Finland restricted drinking for decades (1917–1960s), and South Sudan enforces state-level bans. These varied approaches reveal Prohibition as a fluid tool, shaped by culture, faith,

Related Post

Joe Perry: The Musical Maestro Who Defined Aerosmith’s Fit.

Indian Cinema’s Titan Stars: How Bollywood’s Legendary Actors Redefined Film History

1960s Hairstyles for Guys: The Bold, Poised Revolution That Denebs Modern Grooming Trends

Pat McAfee Nominated For Pro Football Hall Of Fame