Unlocking the Secrets of Water: The Lewis Structure Behind H₂O and Its Molecular Pulse

Unlocking the Secrets of Water: The Lewis Structure Behind H₂O and Its Molecular Pulse

In the endless dance of atoms and bonds, water—H₂O—stands as a humble yet extraordinary molecule, fundamental to life on Earth. Its simple molecular formula belies a complex, elegantly precision-engineered structure governed by valence electron arrangements, culminating in a bent geometry that shapes water’s unique physical and chemical properties. At the heart of understanding water’s behavior lies the Lewis structure—a foundational tool that reveals how electrons are shared, delocalized, or localized, offering profound insights into molecular geometry, polarity, and reactivity.

This article explores how the Lewis structure of H₂O not only maps its atomic architecture but also underpins the very phenomena that define water’s role in nature.

Central to water’s structure is the central oxygen atom, which possesses six valence electrons—two paired and four available for bonding. Each hydrogen atom contributes one valence electron, resulting in a total of eight shared electrons between oxygen and hydrogen.

According to Gilbert N. Lewis’s pioneering electron-pair theory, water forms through two covalent bonds—oxygen sharing electrons with two hydrogen atoms—leaving two lone pairs occupying separate electron domains. These shared pairs anchor the molecule in a tetrahedral electron geometry, which, due to lone pair repulsion, compresses the hydrogen atoms into a bent, V-shaped molecular geometry.

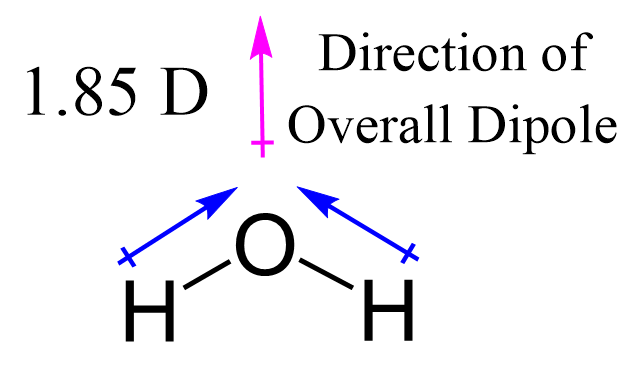

The resulting angle between oxygen-hydrogen bonds is approximately 104.5 degrees, a subtle but critical detail influencing water’s dipole moment and hydrogen bonding capacity. As pioneering chemist Linus Pauling noted, “The bent structure of water is fundamental to its polar nature and ability to dissolve and stabilize biological systems.”

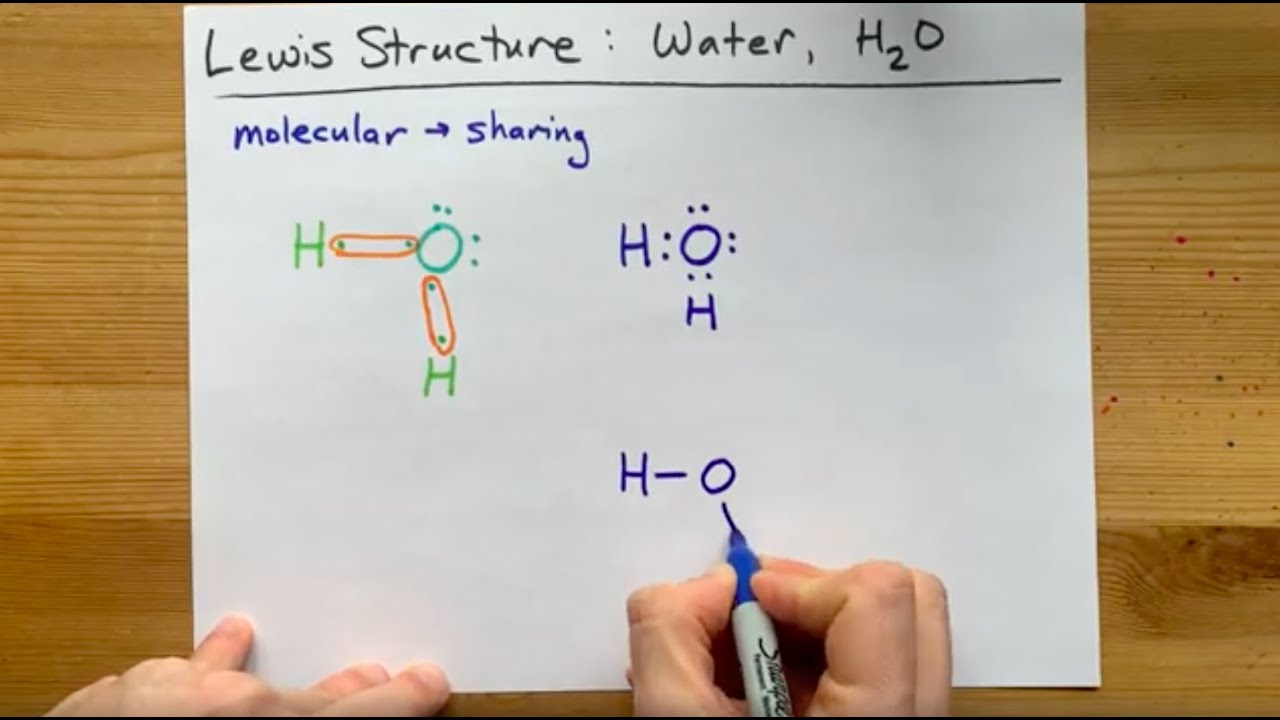

The Lewis Structure: Atomic Arrangement and Electron Distribution The Lewis structure of H₂O formally depicts structure as:

- One oxygen atom at the center, bonded via two single covalent bonds to two hydrogen atoms

- The oxygen atom bears two lone pairs of electrons not involved in bonding

- Each H–O bond consists of two shared electrons (a sigma bond)

“The presence of lone pairs introduces asymmetry, generating a net dipole: oxygen’s electronegativity pulls electron density toward itself, creating a partial negative charge, while the hydrogen ends carry partial positive charges.” Furthermore, the spatial orientation of electron domains explains water’s bent profile—bond angles forced below the ideal tetrahedral 109.5° due to lone pair repulsion, as described by VSEPR (Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion) theory. This distortion is not trivial: it enables hydrogen bonding across water molecules by leaving accessible hydrogen atoms available to electrostatic attraction with oxygen lone pairs of neighboring molecules. The Lewis structure thus lays the groundwork for understanding water’s high cohesion, surface tension, and anomalous density behavior—traits essential to aquatic ecosystems and climate regulation.

Water’s bonding, dictated by its Lewis framework, underpins its role as the universal solvent. The polar nature derived from unequal electron distribution allows water to surround and solvate ions and polar compounds, facilitating biochemical reactions, nutrient transport, and temperature buffering in living organisms. “Without the precise electron pairing shown in the Lewis structure, water’s solvent capabilities—and by extension, most life processes—would be drastically diminished,” remarks Dr.

Rajiv Mehta, a structural biologist. “The arrangement isn’t just visual—it’s functional, parsed in real time by molecular interactions.

The molecule’s resilience and versatility also stem indirectly from its structure’s symmetry and polarity. For example, water’s ability to participate in hydrogen bonding networks—where one molecule’s hydrogen forms a bridge to another’s oxygen—relies directly on the directional alignment dictated by the Lewis diagram.

Each molecule can act as both donor and acceptor, a duality made possible by local charge separation. This dynamic bonding supports water’s high heat capacity, a key factor in stabilizing Earth’s climate and biological systems. “Hydrogen bonds form and break continuously,” says environmental chemist Dr.

Naomi Clarke, “and their formation and strength are rooted in the electron distribution we visualize in the Lewis structure.”

Comparing water with other simple molecular compounds highlights its uniqueness. Unlike linear CO₂, where symmetry dampens polarity, or the tetrahedral methane (CH₄), where symmetry cancels out dipoles, water’s individual bond polarity combined with bent geometry creates a strong dipole moment. In contrast, ammonia (NH₃) shares structural similarities—lone pairs and trigonal pyramidal shape—but differs in electron count and bond angle, resulting in a weaker net dipole.

These comparisons reinforce water’s distinctiveness, driven by the precise electron pairing and geometry captured in its Lewis structure.

What emerges from this molecular scrutiny is a molecule of profound scientific and ecological significance. The Lewis structure of H₂O is not merely a static diagram; it is a dynamic map of electron behavior that governs molecular interactions.

It reveals how electron sharing, lone pairs, and spatial orientation conspire to produce water’s polarity, geometry, and solvent prowess—features indispensable to life and planetary balance.

Understanding water through its Lewis structure transcends academic curiosity: it offers a lens to appreciate biochemistry, environmental science, and materials chemistry. Each bond, each lone pair, each bond angle carries function. Water’s story, written in electrons and geometry, reminds us that even the simplest molecules hold complexities capable of sustaining entire ecosystems.

In exploring H₂O’s structure, we uncover not just chemistry—but the very pulse of life.

Related Post

Msnbc Anchors Whos Who: The influential voices shaping the network’s identity

Unveiled: The Staggering Reality of Tim Robbins's Height Detailed

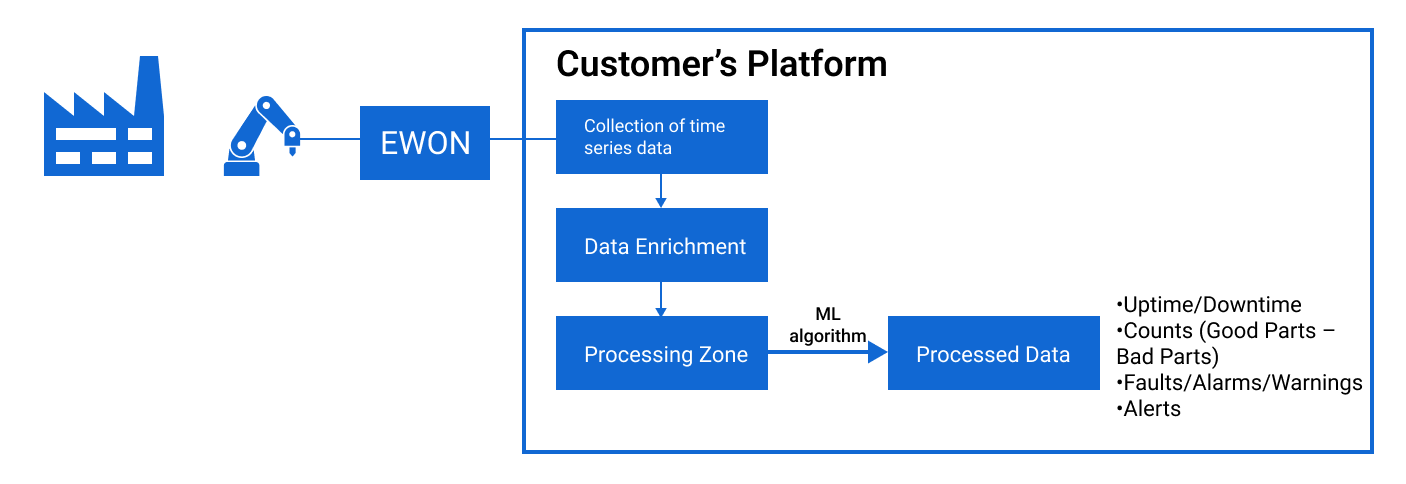

Rmax Site Revolutionizes Industrial Performance Analytics with Real-Time Precision

Putin’s Murmansk Speech: A Deep Dive into Russia’s Arctic Ambitions and Geopolitical Messaging