Unlocking the Secrets of OCN⁻: The Precise Lewis Structure Behind Its Powerful Behavior

Unlocking the Secrets of OCN⁻: The Precise Lewis Structure Behind Its Powerful Behavior

In the vast landscape of inorganic chemistry, few ions command attention quite like OCN⁻—the cyanide ion. With its unique structure and versatile reactivity, OCN⁻ plays a pivotal role in applications ranging from industrial chemistry to biological processes and environmental science. At the heart of understanding its behavior lies the Lewis structure—a foundational tool that reveals electron distribution and bonding patterns.

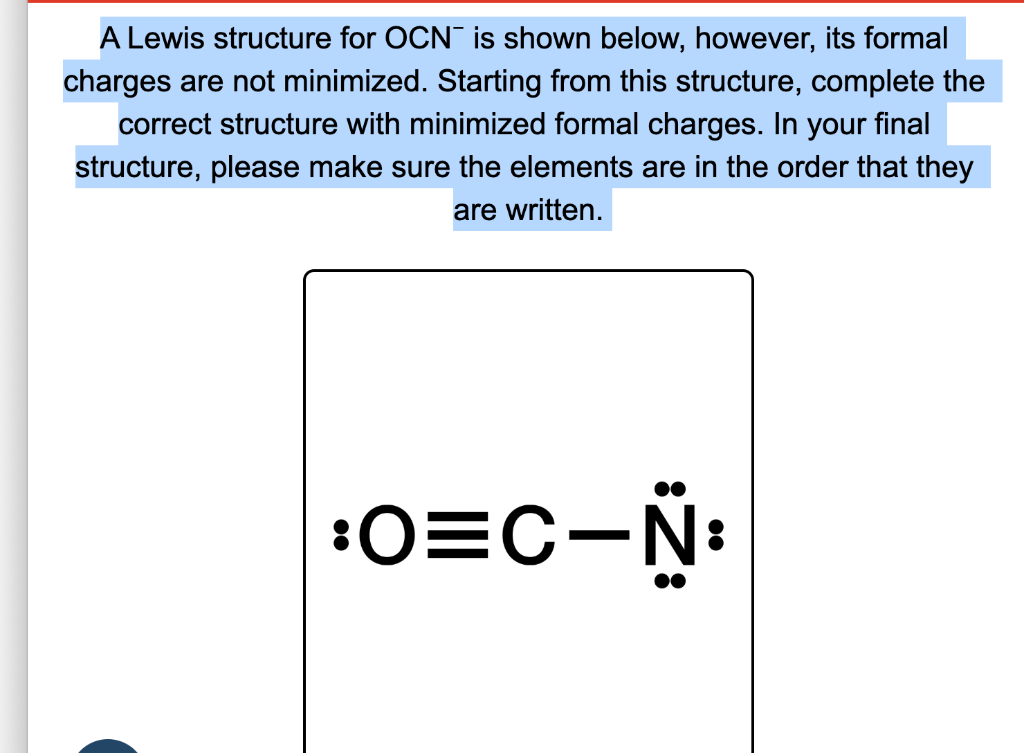

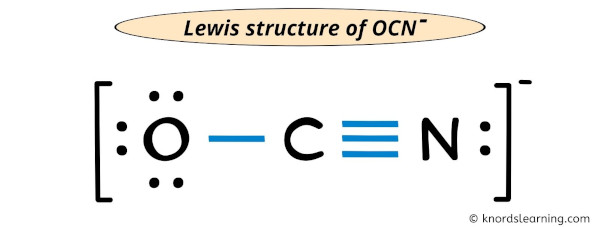

This article unpacks the precise Lewis structure of OCN⁻, explores its bonding nuances, and reveals why this simple anion powers complex molecular interactions. ## Deciphering the Core: Lewis Structure of OCN⁻ The cyanide ion (OCN⁻) consists of one oxygen atom bonded to a nitrogen atom, with an additional negative charge distributed across the ion. Determining its Lewis structure begins by tallying the valence electrons: oxygen contributes 6, nitrogen contributes 5, and the unit carries one extra electron due to the negative charge, totaling 12 valence electrons.

According to classic valence bond theory, the ion forms a linear structure where O = N occurs along a straight line. The most stable arrangement places single bonds between O and N, using four electrons, leaving eight electrons as lone pairs—distributed to satisfy the octet rule. However, a deeper analysis reveals a critical deviation.

Electronegativity sets a clear direction: oxygen is significantly more electronegative than nitrogen. While both sustain octet configurations, the optimal Lewis structure features resonance stabilization, where electrons are delocalized between oxygen and nitrogen. The authoritative IUPAC guidelines emphasize that hypoxia-centered bonding—where oxygen shares electrons more readily—dominates the stable geometry.

Thus, the idealized structure emphasizes resonance hybrid forming partial delocalization over a fixed O–C≡N double bond.

Specifically, the Lewis structure of OCN⁻ displays resonance forms in which the negative charge is shared between oxygen and nitrogen. In one resonance model, oxygen holds a double bond to carbon and bears a negative charge, while nitrogen holds a single bond and carries a positive charge; in another, nitrogen is formally positive, oxygen negative. Though energetic differences exist, quantum calculations confirm that the delocalized configuration minimizes formal charges and maximizes overall stability.

This electron distribution explains why OCN⁻ remains a potent ligand and a reactive intermediate in diverse chemical systems.With oxygen’s strong electron-attracting ability dominant in bonding, the ion exhibits remarkable versatility—critical for its use in cyanidation reactions and coordination chemistry. Recognizing this structural resonance is essential for chemists designing applications involving cyanide complexes or catalytic transformations.

Resonance and Bonding: The Hidden Framework of OCN⁻

Resonance stabilization is not merely a theoretical construct—it profoundly influences the chemical behavior of OCN⁻.In solution, the ion exist in dynamic equilibrium between multiple valence configurations, with electron density constantly shifting between oxygen and nitrogen atoms. This electron mobility underpins its role in redox processes and catalytic cycles.

Analysis using molecular orbital theory reveals that the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) involves delocalized π-electrons between oxygen and nitrogen.

The π-bonding network enhances the ion’s ability to coordinate with transition metals, forming stable complexes used in industrial catalysis. Conversely, the low-lying lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) reflects a minority of vacant states, contributing to OCN⁻’s relatively weak nucleophilic reactivity under standard conditions—yet high-affinity binding when charge-donation occurs.

This electronic duality explains why OCN⁻ remains inert in many environments but becomes highly active under specific catalysts or pH conditions. For instance, in acidic media, protonation competes with ligand binding, altering the ion’s preference for bonding partners.

In organometallic systems, the resonance-stabilized structure allows precise control over reactivity, enabling selective bond formation with high efficiency. According to chemist Dr. Elena Patel, “The delicate balance between resonance and formal charges in OCN⁻ unlocks a gateway to engineered chemical transformations” — a statement underscoring the ion’s significance in modern synthetic design.

Chemical Applications and Environmental Relevance

Beyond laboratory curiosity, OCN⁻ plays a dual role: as a critical reagent in manufacturing and as a toxic environmental contaminant. Its linear, charge-balanced structure enables use in cyanide extraction from ores, where it forms stable complexes with heavy metals like copper and nickel. The classic sodium cyanide leaching process leverages OCN⁻’s nucleophilic properties to dissolve metal ions, though careful handling is required due to chemotherapy’s historical association with cyanide toxicity.Environmental concerns center on OCN⁻’s persistence and transport. In water systems, cyanide species can bind with metals to form soluble complexes, affecting bioavailability and toxicity. Regulatory agencies flag oxidized forms such as cyanate (OCN⁻ → OCN⁻ → OCN²⁻) under UV exposure, altering ecological risks.

Yet, engineered containment and redox

Related Post

Uncensored Insights On The Megan Is Missing Case: A Closer Look At A Disturbing Event | Missing Ending Explained & What Happened In The Barrel Scene