Unlocking Oral Function: The Critical Role of Vomerine Teeth in Human Dental Architecture

Unlocking Oral Function: The Critical Role of Vomerine Teeth in Human Dental Architecture

The human mouth harbors intricate dental adaptations that extend far beyond the visible molars and incisors. Among the lesser-discussed yet profoundly significant structures are the vomerine teeth—small, vestigial buds embedded within the palate’s midline. Though hidden from view, these anatomical features play a nuanced yet vital role in shaping oral function, development, and even evolutionary history.

Understanding their function reveals hidden layers of biology that influence chewing efficiency, speech articulation, and craniofacial stability.

Vomerine teeth are derived from the vomer, a facial bone that contributes to the nasal septum. In adult humans, these structures appear as rudimentary dental navicular-shaped eminences—tenuous relics of a time when our ancestors possessed a more complex dentition.

Modern human jaws typically contain no full-sized vomerine teeth, but microscopic remnants persist in the submucosal tissue of the hard palate, particularly near the midline just behind the alveolar ridge. Though non-eruptive and non-functional in active mastication, their presence suggests deep evolutionary roots tied to ancestral diets requiring specialized palatal processing.

The Hidden Architecture: Anatomical Position and Development

The vomerine teeth sites are located on the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone, forming part of the bony palate that separates the nasal cavity from the oral cavity. Developmentally, these structures arise during embryogenesis alongside the primary and secondary palate, embedded within the mesenchymal tissue that shapes palatal ridges.

While they fail to mineralize into functional crowns or roots in most individuals, histological studies show that residual odontogenic labels persist—evidence of genetic programming that once supported them in primordial forms.

Key anatomical facts include:

- Located midline on the hard palate, approximately 5–10 mm posterior to the maxillary incisors

- Matters are not true teeth but epithelial-to-mesenchymal aggregations resembling buried bud formations

- Permanent presence varies widely; up to 30% of adults exhibit some vestigial remnants, often asymptomatic

- Micro-CT imaging reveals subtle mineralized nodules, indicating latent developmental potential

Unlike the vestigial vomerine teeth in other mammals—such as certain ungulates that use them for grinding fibrous plant matter, this structure’s role in humans is clearly non-eruptive. Their genetic expression persists, linked to broader craniofacial patterning but not to masticatory function.

Functional Significance: Beyond Teeth Sedgment Mini-Duties

Though non-functional in contemporary dentition, vomerine teeth sites exert subtle influences on vital oral mechanics. The palate’s midline is a dynamic interface during chewing, swallowing, and speech—processes dependent on stable skeletal and mucosal architecture.

The vomerine tooth regions contribute to this triad in three key ways:

- Muscular Anchoring Point: Instruments of the palatoglossus and palatopharyngeal muscles anchor near the palatal midline, and the submucosal vomerine sites may enhance soft-tissue stability during force transmission between tongue and hard palate.

- Palatal Rim Integrity: The bony surface where vomerine remnants lie helps maintain the transverse width and vertical contour of the palate—a structure integral to efficient bolus formation during mastication.

- Developmental Resonance: Genetic pathways activating these regions overlap with those governing tooth patterning in primary and secondary dentition, suggesting coordinated embryological signaling that maintains cranial midline coherence.

Functionally, these structures do not assist grinding or tearing. Yet, their spatial presence contributes to biomechanical harmony—preventing localized stress concentrations and supporting palatal elasticity. In resource-limited paleontological contexts, remnants like these hint at adaptive responses to dietary shifts over millennia.

“The palate is not just bone and muscle—it’s a scaffold of evolutionary memory,” observes Dr. Elena Marquez, a craniofacial biologist specializing in developmental dental anatomy.

Clinical Insights: When Hidden Bones Speak

While usually clinically silent, vomerine tooth sites occasionally manifest in diagnostic or surgical contexts. Radiographic imaging, particularly panoramic X-rays and CBCT scans, may reveal these subtle nodules, prompting clinicians to differentiate them from odontogenic tumors or retained primary teeth.

Though often asymptomatic, localized inflammation or infection in the palatal mucosa near these sites can mimic sinusitis or gingival pathology, leading to diagnostic challenges.

Notable case reports indicate:

- Occasional misidentification as impacted mesoperiosteal teeth during orthodontic evaluations

- Rare emergence of benign odontogenic epulis-like growths at midline palatal sites

- Association with palatal cleft anomalies, where disrupted midline development obscures anatomical landmarks

Dentists and oral surgeons emphasize precise imaging and histological analysis when evaluating unanticipated midline lesions. “Vomerine remnants teach us that absence of function does not imply biological irrelevance,” notes Dr. Rajiv Nair, oral pathologist at the Institute of Craniofacial Research.

“Understanding these structures refines diagnostic accuracy and guides targeted treatment.”

Evolutionary Perspective: Echoes of a Primate Past

The vomerine teeth in modern humans are evolutionary echoes—fossil traces of ancestral dentition adapted for powers far beyond our current chewing needs. In early primates and early hominins, more robust palatal dental complexes supported forces from fibrous, tough plant materials. As human diets transitioned toward softer, processed foods, these redundant midline structures diminished in size and functionality.

Yet their genomic imprint endures, preserving developmental pathways tied to palatal form and function.

Comparative anatomy reveals analogous vestigial palatal remnants in other mammals, such as the small molar-like buds in welfare cattle or certain primates. But in humans, these features are unique in their cryptic persistence amid profound dietary and behavioral shifts. They stand as molecular fossils of adaptive trade-offs, illuminating how biological systems retain latent potential even when repurposed or reduced.

Practical Implications: What Dental Professionals Should Know

For clinicians, recognizing vomerine tooth sites enhances diagnostic precision and informs preventive care strategy.

While not routinely palpable, subtle imaging features demand informed interpretation—especially in complex palatal pathologies. Tools like high-resolution cone-beam computed tomography improve visualization, enabling differentiation between normal anatomy and pathological mass.

Key professional takeaways:

- Maintain awareness of midline palatal sites during comprehensive oral assessments

- Interpret incidental mandatory imaging findings with an understanding of vestigial tympanum patterns

- Consider evolutionary biology as a lens for appreciating subtle anatomical variation

Whether viewed through the

Related Post

Estate Sales Abilene Heating Up—Fast-Moving Fast-Sale Events Begin September 8, 2025

Police Car 1970: The Iconic Voice of Law Enforcement on American Roads

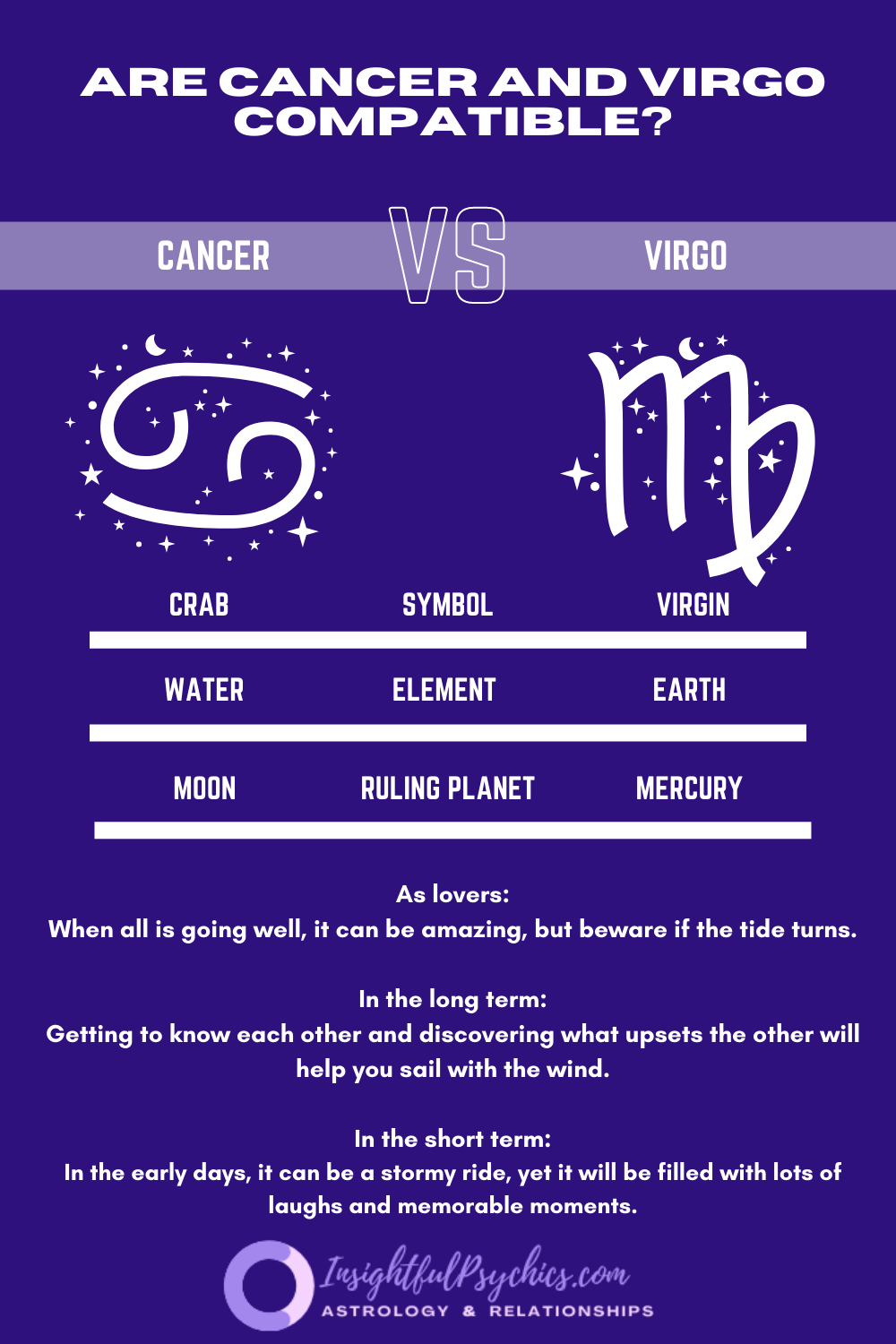

Virgo And Cancer Compatibility: A Celestial Bond Unlocking the Secrets of Love