Unlocking Carbon’s Symphony: How the Bohr Model Illuminates Atomic Structure

Unlocking Carbon’s Symphony: How the Bohr Model Illuminates Atomic Structure

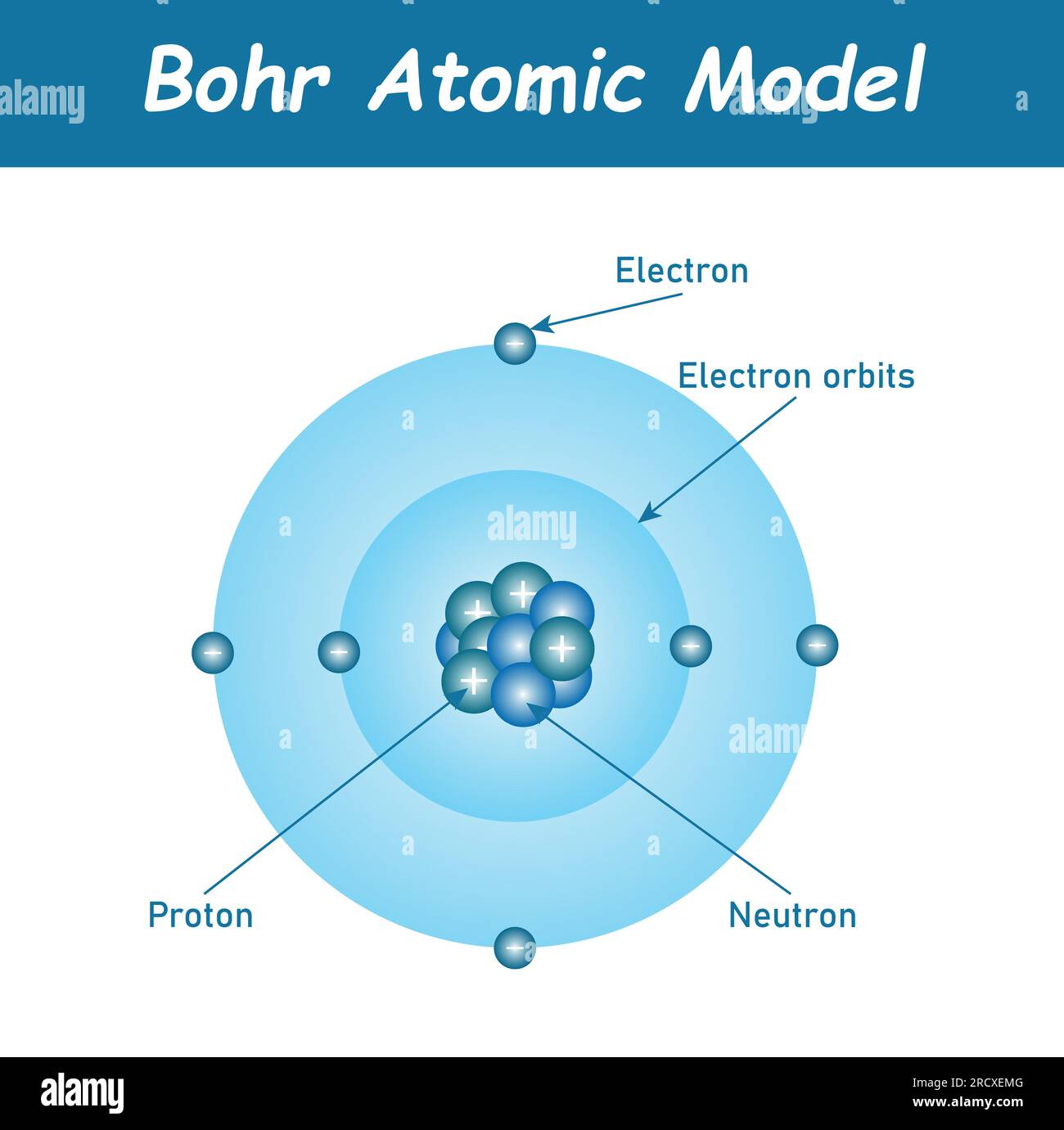

At the heart of carbon’s unique chemistry lies its electron architecture—a story unfolding through the elegant framework of the Bohr Model. This foundational theory, though simplified, provides critical insight into how carbon’s electrons are arranged, stabilizing this element as the cornerstone of organic life and modern materials science. By visualizing electrons in discrete energy levels, the Bohr Model helps explain why carbon exhibits such remarkable versatility in bonding and reactivity.

The Bohr Model: A Foundational Lens on Carbon’s Electron Configuration

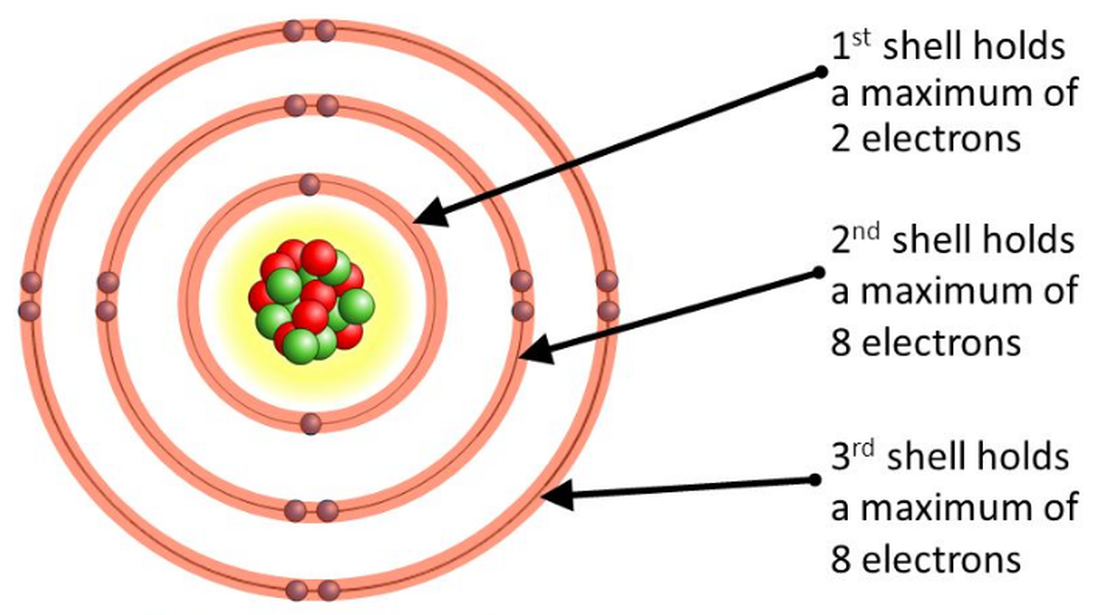

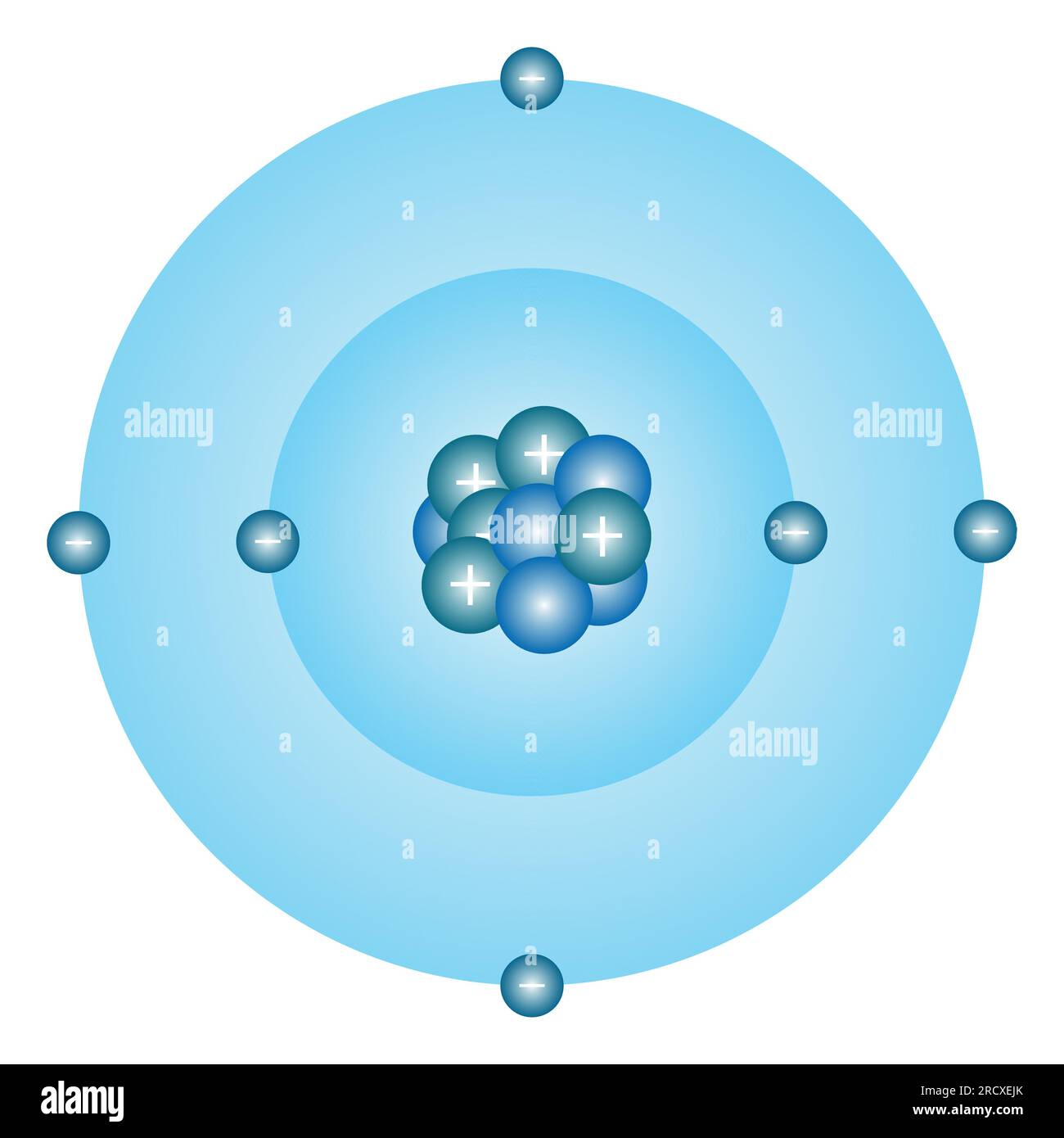

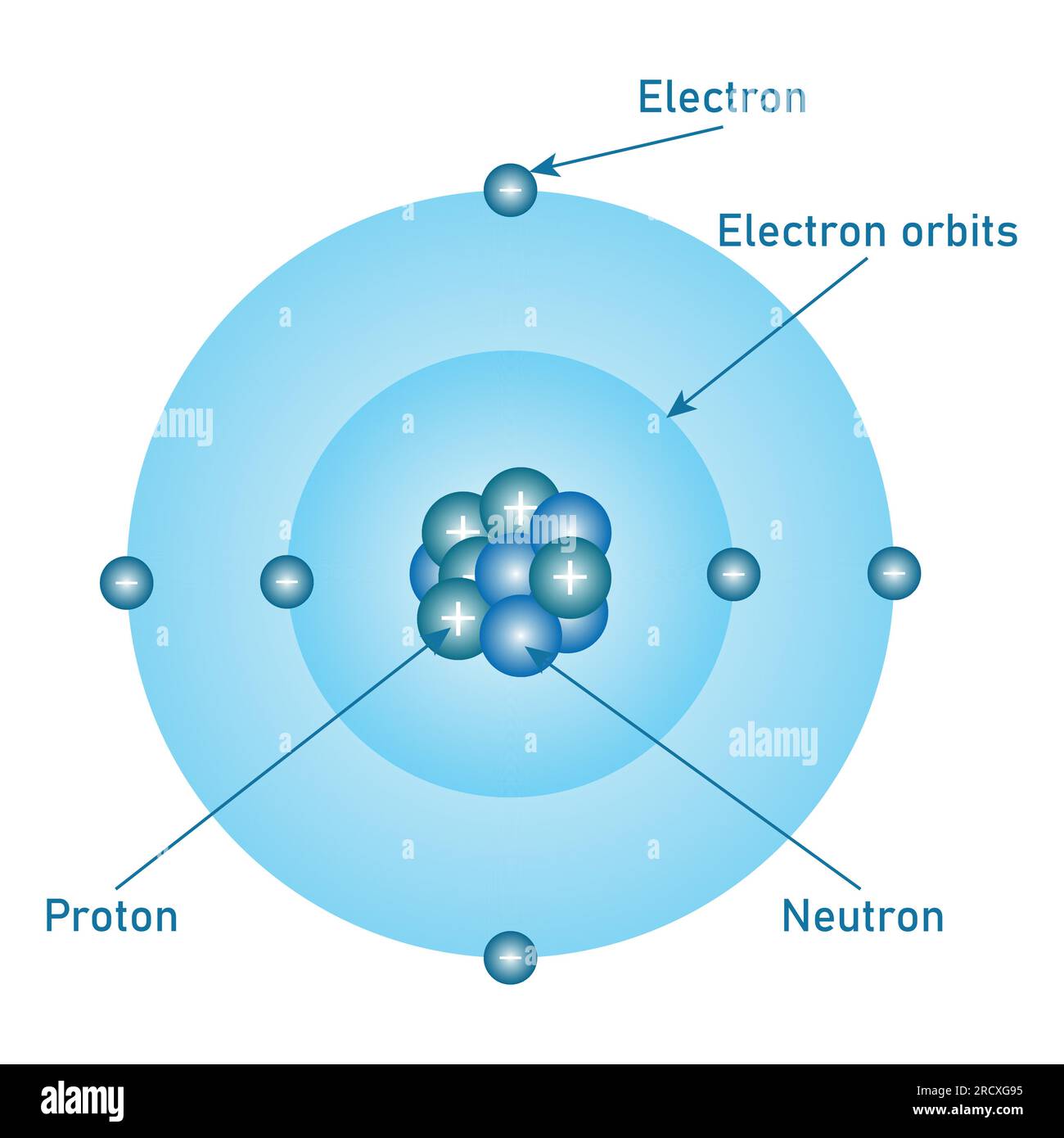

Though Max Bohr’s model emerged in 1913 as a quantum stepping stone, it remains indispensable for grasping carbon’s electron behavior. The model depicts electrons orbiting a nucleus in fixed, quantized orbits, each corresponding to a specific energy level. For carbon—atomic number 6 with six electrons—this arrangement reveals how electrons occupy inner and outer shells, dictating chemical behavior.- **Energy Levels and Electron Shells**: Carbon’s first energy level holds up to 2 electrons in the 1s orbital. The second level contains four electrons, distributed across 2s and 2p orbitals: two in 2s and two evenly in two 2p orbitals (each holding one electron, per Hund’s rule). This configuration—1s² 2s² 2p²—explains carbon’s four valence electrons, the key to its bonding prowess.

- **Quantization and Stability**: Unlike the continuous energy assumption in classical physics, Bohr’s model introduces discrete energy states. Electrons absorb or emit photons only when jumping between levels, ensuring stability when in lower-energy configurations. This quantization underpins carbon’s capacity to form strong covalent bonds without degrading.

- **Resonance and Valence Versatility**: The 2p² arrangement allows carbon to participate in resonance, spreading electron density across adjacent atoms. This delocalization, rooted in orbital overlap, is central to organic chemistry—from carbohydrates to proteins, where carbon’s hybridization enables diverse molecular arrangements.

From Bohr to Today: Carbon’s Ch sexo in Organic Chemistry

Modern understanding of carbon goes beyond Bohr’s circles, integrating quantum mechanics and hybridization theories.Yet the model’s core insights—fixed shells, orbital filling, and electron mobility—remain vital. The 2s orbital, lower in energy and greater in probability near the nucleus, confers stability to core electrons. Meanwhile, the higher-energy, bean-shaped 2p orbitals facilitate bonding.

Carbon’s ability to form four strong covalent bonds arises from combining one electron from 2s and three from 2p, a direct consequence of orbital geometry predicted by extended Bohr-inspired models.

The Role of Hybridization in Carbon’s Bonding Patterns

While not part of Bohr’s original model, the concept of hybridization builds upon its shell theory to explain carbon’s versatility. In organic molecules, carbon frequently undergoes sp³, sp², or sp hybridization—mixing 2s and 2p orbitals to form orbitals optimal for bonding.- **sp³ Hybridization**: In methane (CH₄), carbon’s 2s electron promotes one electron to a 2p orbital, forming four equivalent sp³ hybrids. These orbitals point toward tetrahedral angles (~109.5°), enabling methane’s symmetrical structure. - **sp² Hybridization**: In ethene (C₂H₄), carbon uses sp² hybrids for sigma bonds and retains one unhybridized 2p orbital for π-bonding, forming double bonds—key to reactive unsaturation.

- **sp Hybridization**: In ethyne (C₂H₂), one s and one p orbital combine into two sp hybrids for sigma bonds, while two 2p orbitals form two perpendicular π bonds, producing linear geometry and high bond strength.

From Quantum Foundations to Real-World Applications

The Bohr Model’s legacy extends beyond theoretical diagrams; it underpins technologies relying on carbon’s unique properties. Silicon and graphene—central to microelectronics and advanced materials—derive their functionality from carbon’s bonding framework.Diamond’s hardness and graphene’s conductivity stem from network covalent structures governed by orbital interactions first visualized through level-based electron models. Even in drug design, understanding carbon’s electron positioning enables precise molecular targeting and stability. “Carbon’s beauty lies not just in its abundance,” says Dr.

Elena Rios, a quantum chemist at MIT, “but in how its quantum structure—first sketched by Bohr and refined by generations—enables life’s complexity and modern innovation.” Carbon’s alternating single and double bonds, its ability to form long chains and rings, and its role as a central node in biomolecules all trace back to electron arrangements first conceptualized through quantized orbits. This foundational insight continues to drive discovery in nanotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and sustainable materials.

The Enduring Legacy of the Bohr Model in Carbon Science

Though superseded by sophisticated quantum mechanical models, Bohr’s representation endures as a conceptual anchor.It offers intuitive clarity to electron configurations, bonding, and energy transitions—essential for students, researchers, and engineers alike. Carbon, with its 1s² 2s² 2p² electron count and versatile orbital hybridization, exemplifies how fundamental quantum principles manifest in chemistry’s most vital element. As scientists probe deeper into quantum materials and synthetic biology, the Bohr Model reminds us that simplicity—when rooted in accuracy—can illuminate the most intricate systems in nature.

Related Post

Andre Reed Redskins Bio Wiki Age Family Wife Son Jersey Salary and Net Worth

What Was She As A Child

Est Zone Now: Revolutionizing Real-Time Sports Insights with Cutting-Edge Analytics

Fond Du Lac Obits: Legacies Lost, Loves Forgotten, Lives Found Again in the Echoes of Memory