Unlocking Aluminum’s Potential: The Lewis Dot Structure Behind Its Atomic Architecture

Unlocking Aluminum’s Potential: The Lewis Dot Structure Behind Its Atomic Architecture

At the heart of aluminum’s widespread industrial use lies a fundamental yet often overlooked pillar: its Lewis dot structure. This molecular blueprint—though abstract—holds the key to understanding how aluminum’s atomic arrangement enables its remarkable properties: lightness, conductivity, malleability, and corrosion resistance. By examining Lewis dot structures specific to aluminum, engineers, chemists, and materials scientists reveal how this simple metal’s electron configuration drove its versatility in modern technology.

Far more than a static diagram, the Lewis dot configuration illuminates aluminum’s chemical behavior, bonding tendencies, and role in everything from aerospace alloys to everyday packaging.

Visualizing Aluminum’s Electron Distribution

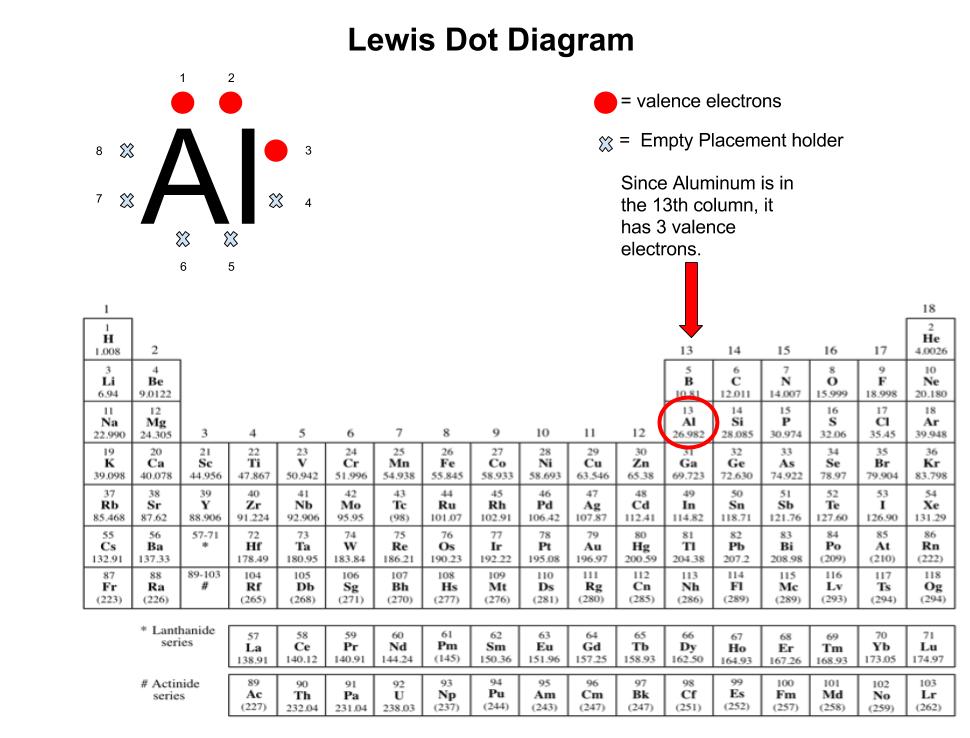

Aluminum, with atomic number 13, possesses three electrons in its outermost shell—positions 2, 3, and 4 on the periodic table. In its pure, elemental form, the electron configuration is 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p¹, meaning aluminum’s valence shell contains exactly three electrons with one unpaired p-electron in the 3p orbital.This solitary p-electron defines the metal’s characteristic reactivity and bonding capacity. Using Lewis dot notation, aluminum’s valence electrons are represented as pairs and lone dots: ··· 3s² ;··· → 3s² ··· (Left orbital) ··· 3p¹ This configuration implies aluminum readily donates its single 3p electron to form metallic or ionic bonds—a hallmark of its role in cationic compounds and crystalline alloys. The absence of fully paired electrons in the outermost shell increases aluminum’s electron mobility, a key factor behind its excellent electrical conductivity.

Unlike inner-shell electrons, which bind tightly and resist movement, the lone p-electron floats freely, facilitating charge transfer across the lattice. <Dot Representations and Bonding Behavior

A crucial insight from Lewis dot structures is how they map bonding patterns. In metallic bonding, aluminum atoms share their valence electrons in a “sea” of delocalized electrons.

Each aluminum atom contributes its single 3p electron to form a collective electron cloud, while the vacant atomic orbitals hold residual positive charge. This electron sharing—though delocalized—stabilizes the lattice and allows free motion, explaining aluminum’s malleability and thermal conductivity. For alumi-Umvlaide or aluminum-based alloys, Lewis structures incorporate transition metals like magnesium or copper, where electrons are partly shared or displaced.

For instance, in Al–Mg alloys, dot diagrams illustrate variable electron donation from magnesium into the aluminum matrix, strengthening the metal without sacrificing lightweight attributes. The structure also shows termination points: - Each dot represents one electron. - Lines indicate shared electron pairs (covalent bonds).

- Unpaired dots reflect emerging cationic sites. These visual cues enable precise predictions about reactivity. Aluminum’s single available electron in the 3p orbital is highly kinetically active, making it prone to oxidation, yet also enabling rapid surface healing—oxidization forms a stable Al₂O₃ layer that prevents further corrosion, a trait central to its long-term durability.

<Beyond the Atom: Engineering Applications Driven by Electron Insight

The power of aluminum’s Lewis dot structure extends beyond theory into material science innovation. In aerospace, where weight savings are critical, engineers exploit aluminum’s electron mobility to design lightweight yet conductive structural components. The structure’s implication—that free electrons traverse the metal lattice with minimal resistance—directly supports applications such as heat-shield substrates and electromagnetic shielding layers.

In electronics, aluminum’s dot structure explains why it excels in circuit boards and interconnects. Its ability to sustain continuous electron flow minimizes signal loss, while oxide layer stability ensures reliable junctions at high frequencies. Lithium-ion batteries, too, leverage aluminum’s valence electron behavior in current collectors, enabling fast electron transfer and prolonged cycle life.

Crafting alloys like 6061-T6 aluminum involves deliberate manipulation of Lewis dot patterns. By introducing magnesium and silicon, metallurgists tailor the distribution of valence electrons, optimizing strength and weldability. “The Lewis dot framework lets us pre-configure how electrons reorganize under stress and heat, predicting how the alloy will perform before fabrication,” explains Dr.

Elena Torres, senior materials scientist at MetalTech Research Institute. Furthermore, the dot notation clarifies why aluminum resists galvanic corrosion less drastically than less noble metals. While reactive, its surface electrons quickly reorganize when exposed to moisture or electrolytes, forming passively protective oxide layers.

“This self-healing mechanism isn’t magic—it’s chemistry written in dots,” says Torres. <

Whether in a smartphone casing, an aircraft wing, or a solar panel frame, every application rests on aluminum’s atomic configuration: a precise, mobile electron shell ready to bond, conduct, and endure. Recognizing this structure is not just an academic exercise—it is the cornerstone of harnessing aluminum’s full potential in a high-tech world.

Related Post

Unraveling the Spousal Condition of Peggy Rea: A Deep Dive into Her Private Life

David Segal New York Times Bio Wiki Age Wife Salary and Net Worth

A Pennsylvania Tragedy Unraveled: Budd Dwyers’ Final Press Conference Exposes a Fatal Day in the Heart of the Keystone State