Trigonal Pyramidal vs. Trigonal Planar: The Electron-Push Wars Shaping Molecular Geometry

Trigonal Pyramidal vs. Trigonal Planar: The Electron-Push Wars Shaping Molecular Geometry

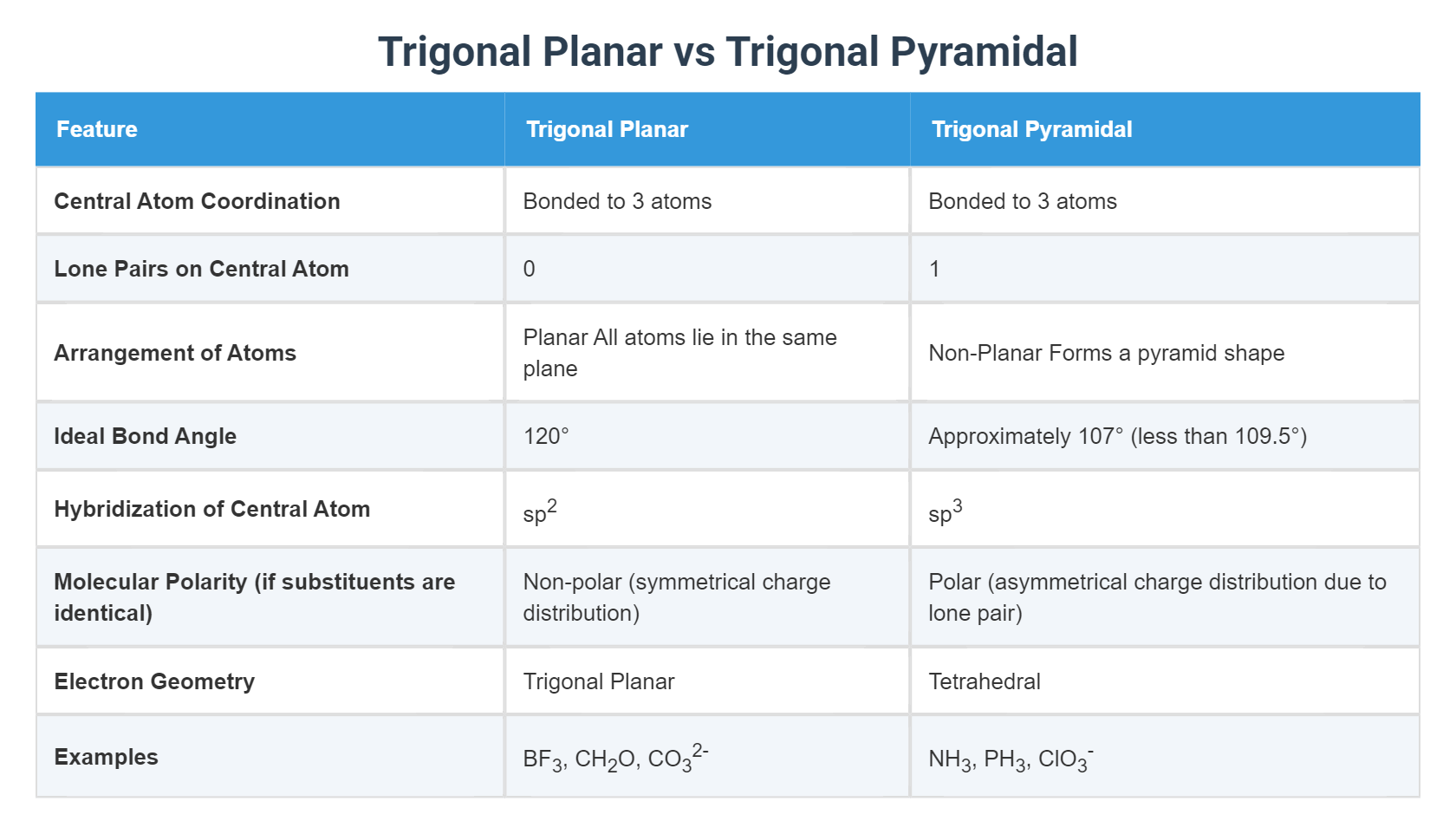

At the heart of chemical structure lies molecular geometry—dictated by how atoms arrange around central elements. Two critical configurations—trigonal pyramidal and trigonal planar—exemplify how electron pairing and repulsion dictate form and function. While both share a central atom bonded to three surrounding atoms (and one or more lone pairs), their distinct spatial orientations arise from fundamentally different electron-electron repulsions.

Understanding these geometries is not just academic; it determines reactivity, polarity, and biological activity in countless compounds. From ammonia’s lonesome rise to methane’s balanced symmetry, the subtle dance of electrons defines molecular destiny.

The Molecular Chessboard: Central Atoms and Lone Pair Dynamics

At the core of trigonal pyramidal and trigonal planar geometries is the central atom’s electronic environment. In trigonal planar systems, the central atom has no lone electron pairs—only three bonding pairs arranged 120 degrees apart in a flat, trigonal plane.

The absence of lone pairs eliminates additional repulsive forces, allowing optimal spacing. In contrast, trigonal pyramidal geometry emerges when a central atom bears one lone pair and three bonding pairs. The lone pair, exerting stronger electron-electron repulsion than bonding pairs, pushes adjacent atoms closer, creating a pyramid-like ascent.

This difference in lone pair count fundamentally alters spatial layout.

With three bonding pairs and zero lone pairs, trigonal planar molecules—exemplified by boron trifluoride (BF₃)—achieve perfect symmetry and equal bond lengths. But when one electron pairs up—say, in ammonia (NH₃)—the lone pair compresses bond angles to approximately 107°, deviating from the ideal 120°. The result is a lopsided, pyramidal form where geometry dictates molecular behavior.

Electron Repulsion Theory: From VSEPR to Real Structure

The Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory provides the framework for understanding these geometries.

According to VSEPR, electron pairs (bonding and non-bonding) repel one another, arranging themselves to minimize energy. Each bond and lone pair occupies a region of electron density, with bonding pairs generally exerting weaker repulsion than lone pairs. In trigonal planar systems, bond-bond repulsions dominate, stabilizing equidistant placement.

When a lone pair enters—trigonal pyramidal—the stronger repulsion from the lone pair distorts the ideal planar structure, shortening bond lengths and increasing molecular asymmetry.

The impact of lone pairs extends beyond mere shape. In ammonia (NH₃), the lone pair generates a region of concentrated electron density above the plane, influencing polarity and hydrogen bonding capacity. Meanwhile, BF₃’s symmetrical, flat structure contributes to its role as a Lewis acid, readily accepting electron pairs.

These functional consequences underscore how geometry is inseparable from chemistry.

Molecular Examples and Electronic Signatures

Numerous molecules illustrate these principles with striking clarity. Trigonal planar systems are epitomized by beryllium trifluoride (BeF₂) and formaldehyde (CH₂O). In BeF₂, beryllium bonds to two fluorine atoms with no lone pairs, producing a rigid, symmetric plane ideal for π-conjugation in materials science and spectroscopy.

Formaldehyde, with a central carbon double-bonded to oxygen and single-bonded to two hydrogens, achieves planarity due to sp² hybridization and minimal lone pair repulsion, a configuration central to organic chemistry and metabolism.

Trigonal pyramidal molecules, by contrast, include ammonia and trimethylamine (CH₃NH₂). In NH₃, the nitrogen atom shares three hydrogen bonds and hosts a lone pair, forcing bond angles below ideal 120°. This distortion enhances NH₃’s basicity—lone pair availability makes it a prime proton acceptor in biological systems, such as in enzyme active sites and neurotransmitter function.

The structural deviation directly enables key chemical roles.

Functional Consequences: Reactivity, Polarity, and Beyond

The geometrical distinctions between these configurations directly shape molecular behavior. In trigonal planar systems like BF₃, symmetry confers electrical neutrality and subtle reactivity; BF₃ readily accepts electrons due to its electron-deficient central atom. Conversely, the pyramidal BF₃ base forms stable adducts, illustrating how shape governs interaction.

Trigonal pyramidal molecules, with their asymmetric electron distributions, often exhibit greater polarity. Ammonia’s lone pair creates a permanent dipole, enhancing solubility in water and participation in hydrogen bonding—critical for its biological roles. Similarly, in phosphine (PH₃), the pyramidal geometry contributes to weaker basicity and distinct reactivity compared to NH₃, highlighting how lone pair environment modulates function.

Beyond polarity, geometry impacts structural stability and function in materials. Trigonal planar conjugated systems, such as in aromatic ring analogs or transition metal complexes like B(C₆H₅)₃, leverage symmetry for electronic delocalization and catalytic activity. Meanwhile, pyramidal NH₃ serves as a springboard for nitrogen-based chemical transformations, including reduction reactions and coordination chemistry.

The Definitive Divide: Geometry as a Molecular Blueprint

Trigonal pyramidal and trigonal planar geometries represent two extremes of electron pair influence—acting as blueprints for molecular identity.

Trigonal planar, defined by symmetry and absence of lone pair compression, delivers stability and electronic delocalization ideal for ligands, catalysts, and strong bases. Trigonal pyramidal, shaped by lone repulsion, introduces polarity and nucleophilic character essential for biological and synthetic processes. The choice between planarity and pyramidal form is not arbitrary; it is a consequence of electron count and the relentless push of repulsion.

From the simplicity of BF₃ to the complexity of NH₃, these shapes illustrate a universal principle: molecular form follows electron behavior. Understanding this interplay transforms abstract concepts into predictive power, guiding drug design, materials innovation, and chemical synthesis with precision. In chemistry’s quiet language, these geometries speak volumes—each bond angle, each lone pair, a silent architect of function.

Related Post

Freeway Closures In Phoenix This Weekend Map: Beat the Traffic Horror as Key Corridors Shut Down

Hisashi Ouchi: The Human Mirror of Radiation’s Lethal Power