The Zamindars of AP World History: Power, Privilege, and Colonial Intrigue

The Zamindars of AP World History: Power, Privilege, and Colonial Intrigue

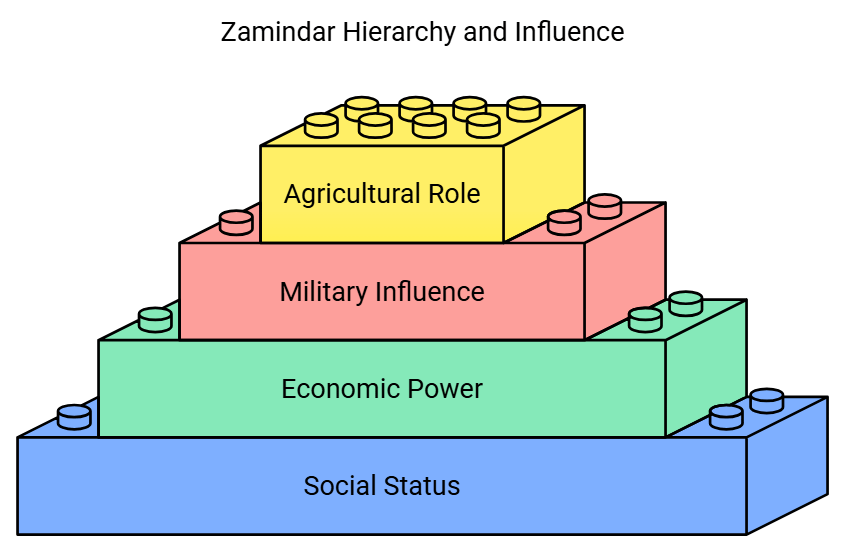

Agents of control and custodians of wealth, the zamindars of British India represent one of history’s most intricate and influential social strata—blending feudal legacy with colonial adaptation during the 18th to early 20th centuries. As key intermediaries between the British Crown and the rural majority, zamindars wielded immense political authority, economic influence, and cultural presence across regions like Bengal, Bihar, and Madras. Their role reshaped land systems, social hierarchies, and imperial governance, leaving an indelible mark on South Asian history.

Understanding the zamindars through the lens of *AP World History* reveals how local power structures were co-opted, redefined, and sustained under colonial rule. The zamindari system emerged from a centuries-old land tenure structure, evolving significantly under Mughal administration before British formalization in the late 18th century. Initially, zamindars collected land revenue on behalf of the empire, functioning as feudal seigneurs with hereditary rights.

However, the British East India Company transformed the system through land revenue settlements—most notably the Permanent Settlement of 1793 in Bengal—where zamindars were legally recognized as proprietors of vast tracts if they met revenue quotas. This shift redefined their role from revenue collectors to landlords with legal title, incentivizing income maximization but often at the expense of peasants.

Under the Permanent Settlement, zamindars became legal proprietors of land, charged with collecting rent from cultivators and paying fixed annual revenues to the state.

Though this system secured short-term revenue for the colonial government, it entrenched a caste of landowning elites bound by rigid profit motives rather than equitable stewardship.

Zamindars accumulated wealth through rising rents and tenant exploitations, yet their power rested precariously on colonial approval.When revenue demands exceeded repayment capacity, farmers faced eviction, transforming zamindars into landlords more interested in profit than rural stability. British reforms like the Ryotwari and Mahalwari systems further complicated their status, yet zamindars retained a unique positioning—legally recognized elites with deep roots in local communities.

Economically, zamindars operated as pivotal nodes in agrarian economies.

Their ability to extract surplus shaped rural class dynamics, deepening the divide between landlord and peasant.

In Bengal, Zamindars controlled massive estates—often spanning thousands of acres—where tenants worked land as rent-payers, vulnerable to arbitrary price hikes and forced le들의. While some zamindars invested in infrastructure—roads, irrigation, schools—these efforts were uneven and primarily self-serving, aimed at maximizing yield and remuneration rather than equitable development. Their wealth reinforced social hierarchies: landownership became a symbol of status, linked to caste identity and regional influence, embedding zamindars firmly within pre-colonial social orders even as colonial law altered their legal standing.

Socially, zamindars cultivated a public persona intertwined with patronage and cultural leadership.

Many funded temples, festivals, and educational institutions, aligning their interests with local traditions to legitimize authority.

Members of zamindar families often served as patrons of art, literature, and nationalist discourse—some even participating in early Bengali Renaissance movements—while maintaining strict social control over their domains.

Yet this cultural engagement coexisted with systemic exploitation. Their household hierarchies relied on a complex network of servants, intermediaries, and tenant overseers, reinforcing a stratified society where mobility for non-zamindars remained extremely limited. Colonial policies, by recognizing zamindars as class-based elites, perpetuated inequality under the guise of tradition.By the early 20th century, zamindars found themselves navigating rising anti-colonial sentiment and reformist agitation.

The abolitionist movements in India increasingly criticized zamindari as a feudal relic, demanding land redistribution and tenant rights. Several provinces, including Bengal and Assam, introduced tenancy reforms curved to limit abuses and expand cultivator protections, curbing zamindars’ economic dominance. Despite these challenges, zamindars maintained substantial political influence, leveraging land wealth to enter colonial legislative councils and shape agrarian policies behind closed doors. Their ability to adapt—balancing collaboration with the Crown against cautious accommodation of reform—ensured their survival as a critical, if contested, social class. The zamindars’ legacy in *AP World History* transcends regional boundaries, illustrating how colonial powers restructured indigenous governance systems to serve imperial economic ends.

Their evolution from Mughal-era revenue agents to colonial intermediaries underscores the resilience and malleability of local elites under foreign rule. Yet their history is also one of contradiction: patrons of culture and reform, yet enforcers of cultivator oppression. Today, the zamindars stand as a powerful case study in the interplay of power, legacy, and change—reminders that history is not shaped solely by empires, but by the local actors who navigate, resist, and redefine them.

Related Post

Mugshot: Diana Lovejoy Arrested for Murdering Her Husband | Where Is She Now?

Chelsea’s Italian Managers: The Tactical Revolution That Redefined a Club

Shannon Miller NBC’s CT: The Identity Behind the Husband That Captured Public Attention

Parker Schnabel Gold Rush Bio Wiki Age Height Girlfriend and Net Worth