The Visionary Who Calculated the Future: Charles Babbage and the Birth of Mechanical Computing

The Visionary Who Calculated the Future: Charles Babbage and the Birth of Mechanical Computing

Charles Babbage, often hailed as the father of the computer, was decades ahead of his era in conceiving machines capable of automated calculation—machines that laid the foundational principles of modern computing. Though best known for his unfinished analytical engines, Babbage’s journey reveals a relentless pursuit of precision, logic, and mechanical efficiency that reshaped the landscape of mathematics and engineering. His inventions were not mere inventions; they were radical assertions that numbers could be processed without human error—if only the machines were built.

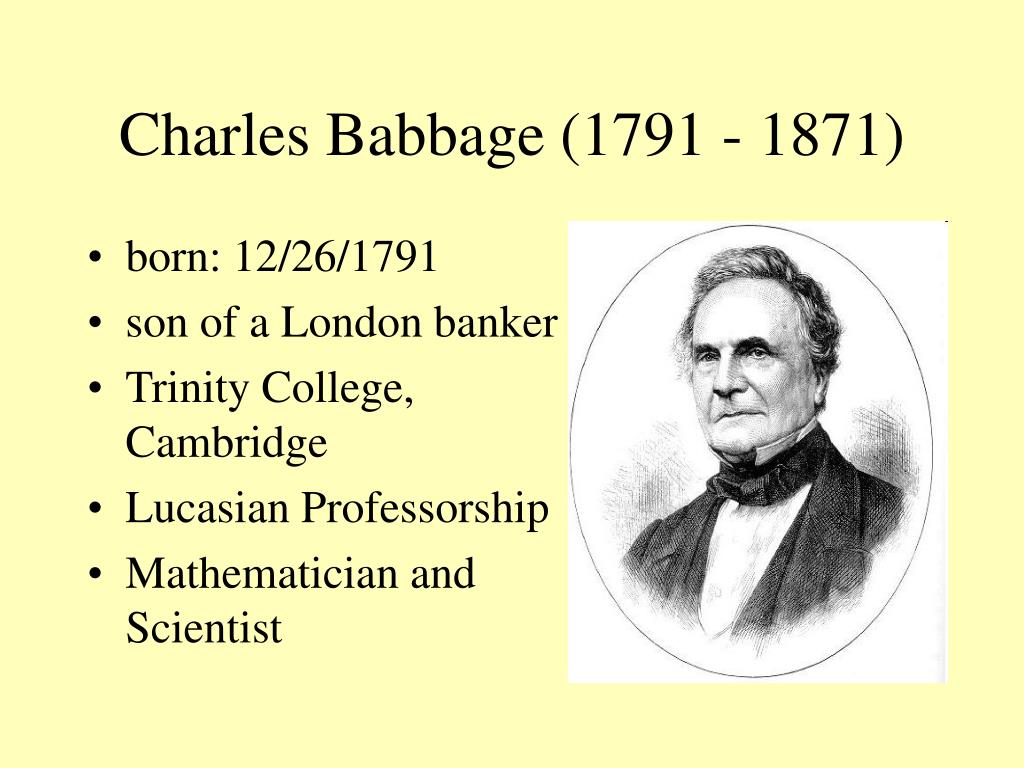

Born in 1791 in London, Babbage’s early fascination with mathematics and machines set him on a path that would challenge the limits of 19th-century technology. His academic training at Trinity College Cambridge exposed him to the chaotic inconsistencies in mathematical tables, fueling his resolve to create machines that would eliminate human fallibility. As he famously stated: “We may be tempted to regard calculation simply as a mechanical operation, but its true essence demands accuracy, consistency, and reliability—qualities no hand-operated system could fully deliver.”

Babbage’s first major project, the Difference Engine, was conceived in 1822 as a mechanical contraption designed to compute polynomial functions automatically and eliminate errors in naval and scientific tables.

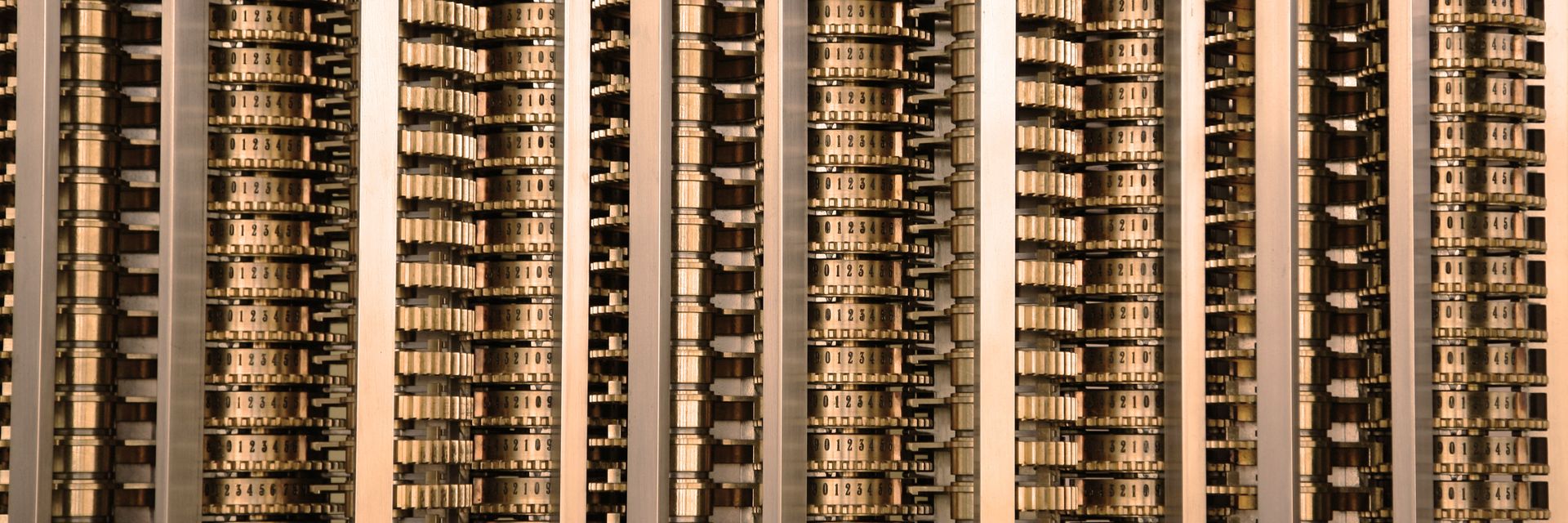

Using a system of interlocking gears and a treadle-powered engine, the Difference Engine aimed to perform indexed calculations through repeated addition—a concept that, while rudimentary by today’s standards, introduced the revolutionary idea of a machine executing pre-programmed computations. The machine’s architecture relied on binary ratios in gear ratios to generate results, a sophisticated approach for the time. Cryptographer and historian Doron Swade notes: “Babbage saw the Difference Engine not just as a calculator, but as a blueprint for automation—an early forecast of how machines might think.”

Despite securing initial government funding, the Difference Engine was never completed in Babbage’s lifetime.

Technical challenges, precision tolerances beyond contemporary manufacturing, and political indifference stalled construction. Yet the blueprint itself became a milestone—a detailed manifesto of engineering ambition. The reconstructed version built at London’s Science Museum in the 1990s confirmed that Babbage’s design was mechanically sound, validating his foresight and technical rigor over 180 years ago.

Building upon the Difference Engine’s incomplete promise, Babbage developed an even more sweeping design: the Analytical Engine, unveiled in conceptual form by 1837. This machine marked the first comprehensive design for a general-purpose computer—featuring a central processing unit (the “Mill”), memory (the “Store”), input via punched cards (inspired by Jacquard looms), and output capabilities. It was programmable, conditional, and capable of looping—features that align with modern CPU architecture.

Babbage wrote: “I propose a machine that shall receive instructions from punched cards, perform calculations, and store intermediate results—all without human intervention.”

The analytical engine’s architecture was decades ahead of its time. It included: - A high-speed processor (the Mill), - Archival memory (the Store, designed to hold 1,000 50-digit numbers), - Conditional branching allowing self-correction and decision-making, - Output mechanisms for printing or mechanical recording. However, funding and engineering constraints prevented physical realization.

Babbage’s intricate drawings were detailed, but construction required metallurgy and machining precision beyond 19th-century capacity. The machine remained theoretical, though visionary leaders such as Ada Lovelace—who translated and expanded on Babbage’s notes—recognized its immense potential. Lovelace famously described the Analytical Engine as a device “not merely to follow order, but to create,” anticipating software as distinct from hardware.

Babbage’s influence extended far beyond his machines. He founded the atineum Society, promoted rigorous scientific methodology, and critiqued institutional resistance to innovation. His writings championed the idea that machines should extend human intellect, not replace it entirely—a philosophical stance echoing in today’s debates around artificial intelligence.

The British government’s eventual recognition came decades after Babbage’s death in 1871, when symbolic plaques acknowledged his role as a pioneer whose work bridged mechanical innovation and computational theory.

Though never built in his lifetime, Babbage’s designs inspired generations. In 1991, a working replica of the Difference Engine No.

2 was completed under the Babbage Engine Project, proving the feasibility and precision of his original concept. Modern simulations of the Analytical Engine further confirm his algorithms would function as intended. His legacy endures not only in hardware but in the fundamental idea that logic can be encoded, machines can reason, and computation is humanity’s next evolutionary tool.

Charles Babbage’s genius lay not in finishing machines, but in daring to imagine them—machines that computed, learned, and anticipated, centuries before silicon and software made them possible. His work remains a testament to the power of visionary thinking: the belief that the future can be built, one gear and algorithm at a time.

Related Post

Charles Babbage: The Visionary Father of the Computer

Set Up Cricket Bridge Pay My Bill Mahaepic: The Ultimate On-Demand Solution for Smart Cricket Fans

Unveiling The Life Of Jasmine Crockett’s Spouse: A Journey Of Love And Partnership

Ryan Wolf KABB Bio Wiki Age Height Wife Salary and Net Worth