The Trigonal Pyramidal Bond Angle: A Quantum Playground of Electron Repulsion

The Trigonal Pyramidal Bond Angle: A Quantum Playground of Electron Repulsion

The trigonal pyramidal bond angle—narrower than the ideal 109.5° of a perfect tetrahedron—lies at the heart of molecular geometry, dictating the spatial arrangement of atoms in countless key compounds. This precise angular deviation arises fundamentally from VSEPR theory, where electron pair repulsion shapes molecular structure. Beyond textbook definitions, the trigonal pyramidal geometry reveals a dynamic interplay of quantum mechanics, electron symmetry, and environmental influences, forming a cornerstone of molecular-scale interactions.

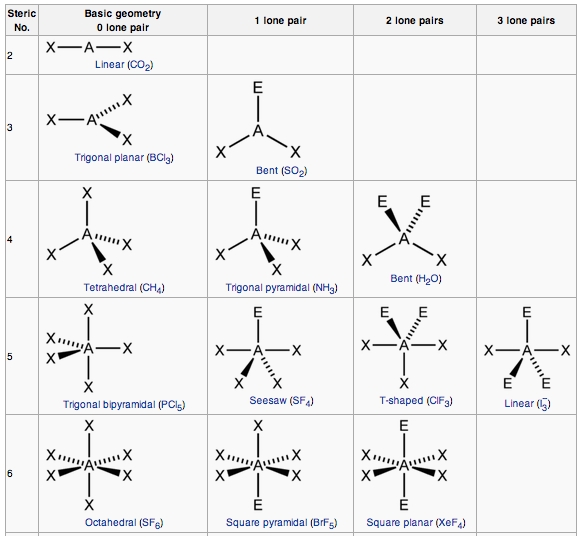

At the core of the trigonal pyramidal configuration is the concept of lone pair-electron pair repulsion. In molecules such as ammonia (NH₃) and water (H₂O), a central atom bonded to three others retains one lone pair, compressing bond angles from tetrahedral symmetry. This distortion follows a predictable order: the lone pair exerts greater repulsive force than bonding electron pairs, collapsing the angle to approximately 107°—a compromise between electronic stability and atomic spacing.

"The reduction in bond angle is not arbitrary," explains Dr. Elena Marquez, a physical chemist at MIT. "It reflects the fundamental battle between Coulombic attraction, kinetic energy minimization, and electron cloud overlap." From a quantum mechanical perspective, the bond angle is deeply tied to orbital hybridization.

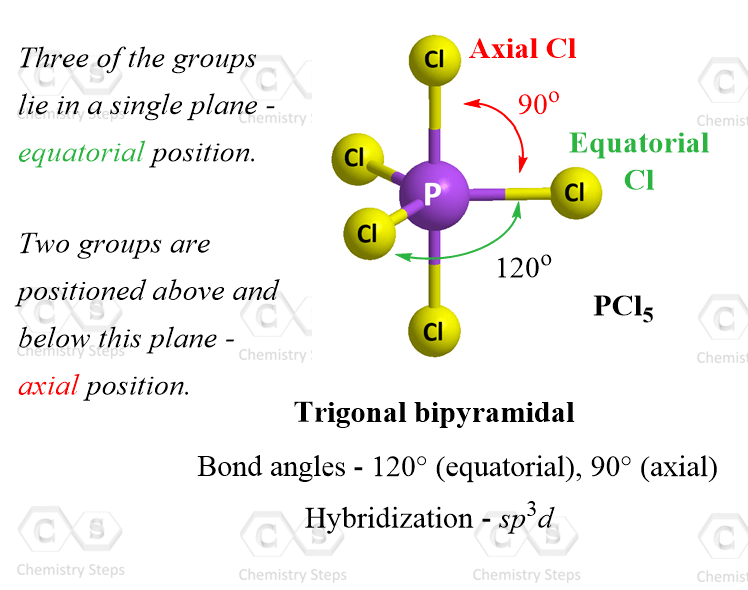

In trigonal pyramidal arrangements, the central atom undergoes sp³ hybridization, forming four orbitals oriented toward the vertices of a tetrahedron. The presence of a lone pair introduces uneven electron density, altering orbital interactions and bonding trajectories. These perturbations manifest in measurable energy shifts, quantified through ab initio calculations and density functional theory (DFT) simulations.

Results confirm that the pyramidal distortion reduces s-character in bonding orbitals, favoring p-like electron distribution—a subtle but critical factor in molecular reactivity. Environmental factors further modulate the effective bond angle, illustrating the sensitivity of molecular structure to external conditions. In polar solvents, dielectric screening alters electrostatic interactions, often slightly expanding the angle due to reduced lone pair compression.

Temperature-induced thermal motion increases atomic vibrational amplitudes, while pressure can force atoms closer, constraining angular flexibility. For instance, ammonia in aqueous solution exhibits a measurable deviation from its ideal gas-phase angle, underscoring the dynamic nature of bonding geometry in real environments. The implications of precise bond angle control extend far beyond theoretical interest.

In catalysis, the trigonal pyramidal geometry of transition metal complexes dictates substrate selectivity and reaction pathways. In biochemistry, hydrogen bonding networks in proteins and nucleic acids depend on the exact orientation of donor-acceptor lone pairs and bond angles—critical for folding, stability, and function. Even in materials science, molecules with tailored pyramidal angles are used in molecular sieves and proton-conducting membranes, where geometric precision enhances performance.

Quantifying deviations from ideal bond angles demands sophisticated experimental techniques. X-ray crystallography offers atomic-resolution snapshots, revealing subtle bond length and angle variations in crystalline solids. In gas-phase molecules, laser diffraction and rotational spectroscopy detect isotopic shifts and vibrational modes sensitive to angular distortion.

Meanwhile, computational chemistry bridges theory and observation, using quantum methods to simulate electron distributions and predict angular changes under varying conditions. Despite decades of study, key challenges persist. Accurately modeling lone pair behavior in electronegative atoms remains computationally intensive, requiring corrections for relativistic effects and spin-orbit coupling.

Moreover, dynamic molecular environments complicate static measurements—real molecules flicker between transient geometries influenced by thermal and solvent fluctuations. “We’re moving toward time-resolved structural characterization,” notes Dr. Amir Patel, a computational chemist at Stanford.

“Understanding bond angle dynamics in real time could unlock new design principles for drugs and catalysts.” Ultimately, the trigonal pyramidal bond angle serves as a microcosm of chemical complexity—where quantum principles meet environmental variables to shape molecular destiny. Its narrow aperture of ~107° reflects a universe governed by compromise: between attraction and repulsion, rigidity and flexibility, theory and reality. This elegant compromise enables the very chemistry essential to life, industry, and innovation.

From ammonia’s lone-laden l encouragement to water’s balanced pyramidal embrace, the trigonal bond angle stands as a silent architect of molecular behavior. Harnessing its subtleties reveals not only the rules of atomic ordering but also pathways to advancing technology, medicine, and materials—one precise angle at a time.

The Quantum Roots of Angular Deviation in Trigonal Pyramidal Molecules

The deviation from ideal tetrahedral angles (~107°) stems from electron pair repulsion governed by VSEPR theory, where lone pairs exert greater repulsion than bonding pairs. This quantum-driven distortion arises as lone pairs occupy hybridized orbitals with asymmetric electron density, altering orbital overlap and bond lengths.Ab initio calculations confirm that even minor perturbations in

Related Post