The Power Behind the Numbers: Understanding the Determinant of a 2x2 Matrix

The Power Behind the Numbers: Understanding the Determinant of a 2x2 Matrix

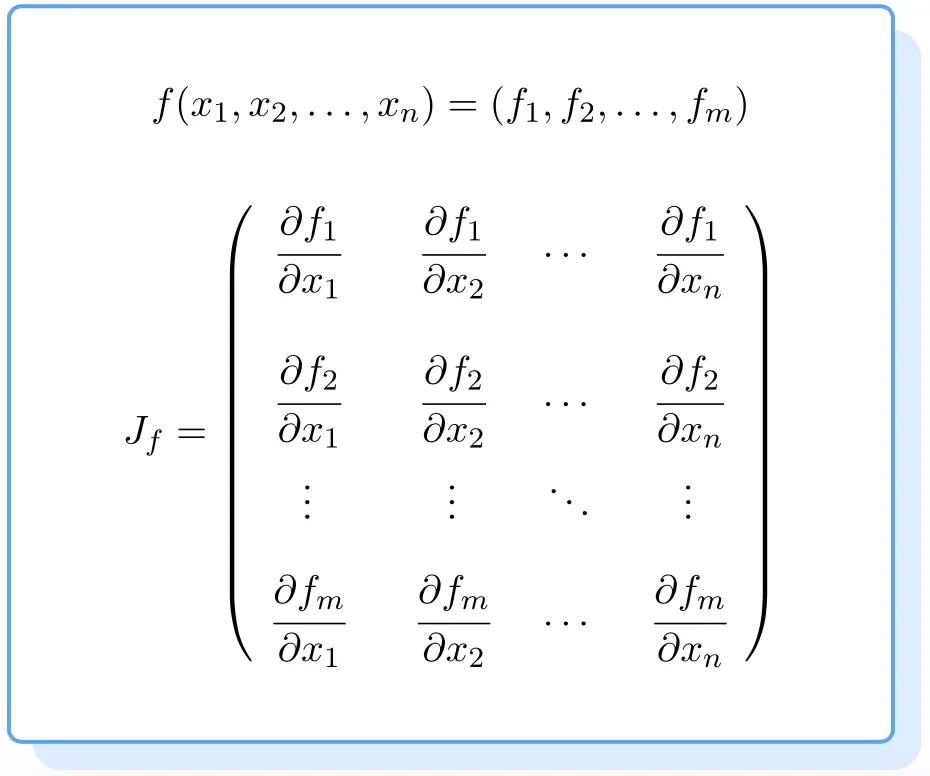

The determinant of a 2x2 matrix is far more than an abstract algebraic concept—it is a powerful, concise value that reveals deep structural properties of linear relationships. Defined simply, the determinant of a matrix [[a, b], [c, d]] is computed as ad – bc. Though its formula is elementary, its implications span geometry, engineering, physics, and data science.

Far from being mere computation, this scalar result encodes critical information about invertibility, area scaling, and system behavior—making it indispensable in both theoretical and applied mathematics.

At its foundation, the determinant serves as a screen for matrix properties. For a 2×2 matrix [[a, b], [c, d]], if det = ad – bc ≠ 0, the matrix is invertible and represents a non-degenerate linear transformation.

This non-zero condition ensures that the transformation preserves dimensionality; there is no collapse into a lower rank. In geometric terms, such a matrix maps the unit square in the plane to a parallelogram with a positive or negative area equal to |det|. The sign indicates orientation—positive if the vertex order preserves clockwise or counterclockwise winding, negative otherwise.

“The determinant tells the story of how space is reshaped,” explains mathematician Dr. Elena Marquez, “a single number capturing transformation integrity.”

When det = 0, the matrix fails to be invertible. The two column vectors become linearly dependent, lying along the same line, and the transformation collapses the plane into a line or a point.

This condition signals a singular system, often indicating redundancy in equations or incompatible constraints. “A zero determinant flags critical problems: no unique solution, impossible scenarios, or degenerate behavior,” notes engineering analyst Raj Patel. In applied contexts, this detection is vital—whether diagnosing circuit design flaws, analyzing data covariance, or simulating structural stability.

Geometric Interpretation: Area, Transformation, and Orientation

The determinant serves as a geometric scale factor for linear mappings.Consider the unit square anchored at (0,0), (1,0), (1,1), and (0,1). When transformed by a matrix [[a, b], [c, d]], this square becomes a parallelogram whose area equals the absolute value of ad – bc. This extends intuition: stretching, rotating, or shearing preserves the shape’s essential geometry, only scaling its area by the determinant’s magnitude.

When det = 1 or –1, the transformation is area-preserving and orientation-preserving—critical in computer graphics, robotics, and physics simulations requiring fidelity to physical space. Consider the classic shear transformation [[2, 1], [0, 1]]. Applying it to the unit square distorts it into a parallelogram with base doubled and height unchanged.

Its determinant, (2)(1) – (1)(0) = 2, confirms area doubling. The positive sign also means the transformation maintains counterclockwise orientation. Conversely, [[1, 3], [0, 1]] has determinant 1, preserving area and orientation amid vertical stretching.

These geometric insights allow engineers and scientists to verify transformation correctness at a glance.

Orientation, encoded in the determinant’s sign, affects physical interpretations. In thermodynamics, for instance, a heat exchanger transformation must conserve directional relationships—without a positive determinant, physical laws may reverse, leading to unphysical results.

In computer vision, maintaining orientation ensures realistic 3D reconstructions from 2D projections. “The sign is more than a number—it’s a truth value of spatial consistency,” remarks Dr. Marquez.

Thus, the determinant’s sign is as vital as its magnitude in modeling real-world systems.

Applications Across Disciplines: From Einstein to Machine Learning

The determinant’s influence stretches across scientific and technical domains. In physics, matrix determinants underpin electromagnetic field analysis, where Faraday’s and Maxwell’s equations rely on 2D tensor transformations whose invertibility ensures consistent field behaviors.In structural engineering, the stiffness matrix of a truss determines whether a structure is stable—invertible with positive determinant indicating a rigid, predictable system.

In data science, the determinant plays a foundational role in multivariate analysis. The determinant of a covariance matrix quantifies data spread in multiple dimensions.

A larger determinant indicates greater variability, guiding feature selection in machine learning models. Singular matrices—those with zero determinant—signal multicollinearity, where variables redundantly predict outcomes, undermining model reliability. “Removing variables that drive the determinant to zero is often the first step in ensuring model robustness,” observes statistician Dr.

Amara Lin. Beyond linear algebra, determinants extend to higher dimensions and abstract spaces. In quantum mechanics, 2x2 matrices model spin states, and their determinants describe probabilities and measurement outcomes.

In economics, determinant sign tells us whether market pair transformations preserve predictive structure. Every application, though diverse, hinges on the same core idea: a compact scalar revealing whether a transformation is valid, invertible, and geometrically meaningful.

Computing the Determinant: Best Practices and Common Pitfalls

Computing the determinant of a 2x2 matrix is straightforward but requires precision.The formula det = ad – bc is counterintuitive to beginners but unambiguous: multiply diagonal elements, subtract the product of off-diagonals. This simplicity enables rapid validation of matrix properties, yet errors frequently arise from sign mistakes or misindexing.

Common pitfalls include confusion between [[a, b], [c, d]] and [[a, c], [b, d]], which invert determinant signs, and overlooking unit order.

For instance, [[2, 3], [1, 4]] correctly yields det = 8 – 3 = 5, while [[1, 3], [2, 4]] would incorrectly compute 1×4 – 3×2 = –2. Ininverse operations hinge on accurate sign, affecting matrix invertibility: det ≠ 0 means invertible, det = 0 signals dependency. “Always verify the matrix element positions—one typo flips the outcome,” warns Patel.

Using symbolic computation tools can catch errors, but understanding manual calculation remains essential for deeper insight.

The Determinant as a Gateway to Linear Algebra Mastery

Far from a mere computational tool, the determinant of a 2x2 matrix embodies the rich interplay between algebra, geometry, and application. It deciphers invertibility, quantifies area change, and preserves essential orientation—making it a cornerstone of linear algebra.In classrooms, research labs, and industrial write-ups, this value bridges abstract theory and tangible results. “Understanding the determinant is like learning to read a map before traveling,” explains Marquez. “Once you grasp it, every matrix tells a story—of stability, transformation, and truth encoded in numbers.” For modern science and technology, mastering this determinant is not just helpful—it’s indispensable.

Related Post

Matilda Ledger: The Parents Behind The Star That Defined a Generation

Holing the Line: How UIC Zoom Zoom Fails—And How to Protect Your Privacy from a Critical Mistake