The Invisible Engine: Unlocking the Inputs and Outputs of Photosynthesis

The Invisible Engine: Unlocking the Inputs and Outputs of Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is the life-sustaining process by which green plants, algae, and some bacteria convert sunlight into chemical energy, forming the foundation of most terrestrial and aquatic food webs. More than a biological curiosity, this intricate biochemical cascade transforms solar energy, carbon dioxide, and water into glucose and oxygen—compounds essential not only for plant growth but also for every aerobic organism on Earth. Understanding the precise inputs and outputs of photosynthesis reveals the elegance of nature’s energy conversion system and its profound global significance.

At its core, photosynthesis relies on three primary inputs: light energy, carbon dioxide (CO₂), and water (H₂O). Each plays a non-redundant role in driving the process. Solar radiation enters through specialized pigments in leaf chloroplasts, primarily chlorophyll a and b, which absorb light most efficiently in the blue and red wavelengths.

“Chlorophyll captures photons, exciting electrons that power the electron transport chain,” explains Dr. Elena Rodriguez, an environmental biochemist at the Global Institute of Bioenergetics. This initial energy capture sets off a chain reaction that generates ATP and NADPH—energy carriers crucial for subsequent stages.

Carbon dioxide’s role is equally vital. Fixed from the atmosphere through microscopic openings called stomata, CO₂ enters leaves and is incorporated into organic molecules during the Calvin cycle. “Plants essentially use CO₂ as the carbon backbone for building sugars,” notes Dr.

James Tran, a plant physiologist at the National Botanical Research Network. Without consistent CO₂ supply, the synthesis of glucose halts, halting growth and energy storage. Water serves a dual purpose: it supplies electrons for the photosynthetic machinery and provides hydrogen ions to form glucose.

When absorbed by roots from soil, water molecules (H₂O) are split during the light-dependent reactions—a process known as photolysis—releasing oxygen as a byproduct. “Water isn’t just a solvent; it’s a direct reactant in generating the reducing power necessary to build nutrients,” explains Dr. Rodriguez.

The oxygen released into the atmosphere accounts for approximately 21% of Earth’s breathing air—making photosynthesis humanity’s most reliable oxygen source. The output of photosynthesis is a balance of organic and inorganic compounds, with glucose (C₆H₁₂O₆) at the center. This six-carbon sugar acts as both an energy source and a building block for larger molecules: starch for storage, cellulose for structural support, and proteins when combined with nitrogen.

Beyond glucose, photosynthesis yields oxygen (O₂), which supports animal respiration, aerobic decomposition, and ozone layer maintenance. A concise summary of the inputs and outputs reveals the fundamental equation:

The inputs—light energy, carbon dioxide, and water—fuel the synthesis of glucose (C₆H₁₂O₆) and oxygen (O₂), with solar radiation driving electron excitation, CO₂ feeding the carbon skeleton, and water providing electrons and hydrogens. This transformation underpins global energy flow and atmospheric chemistry.

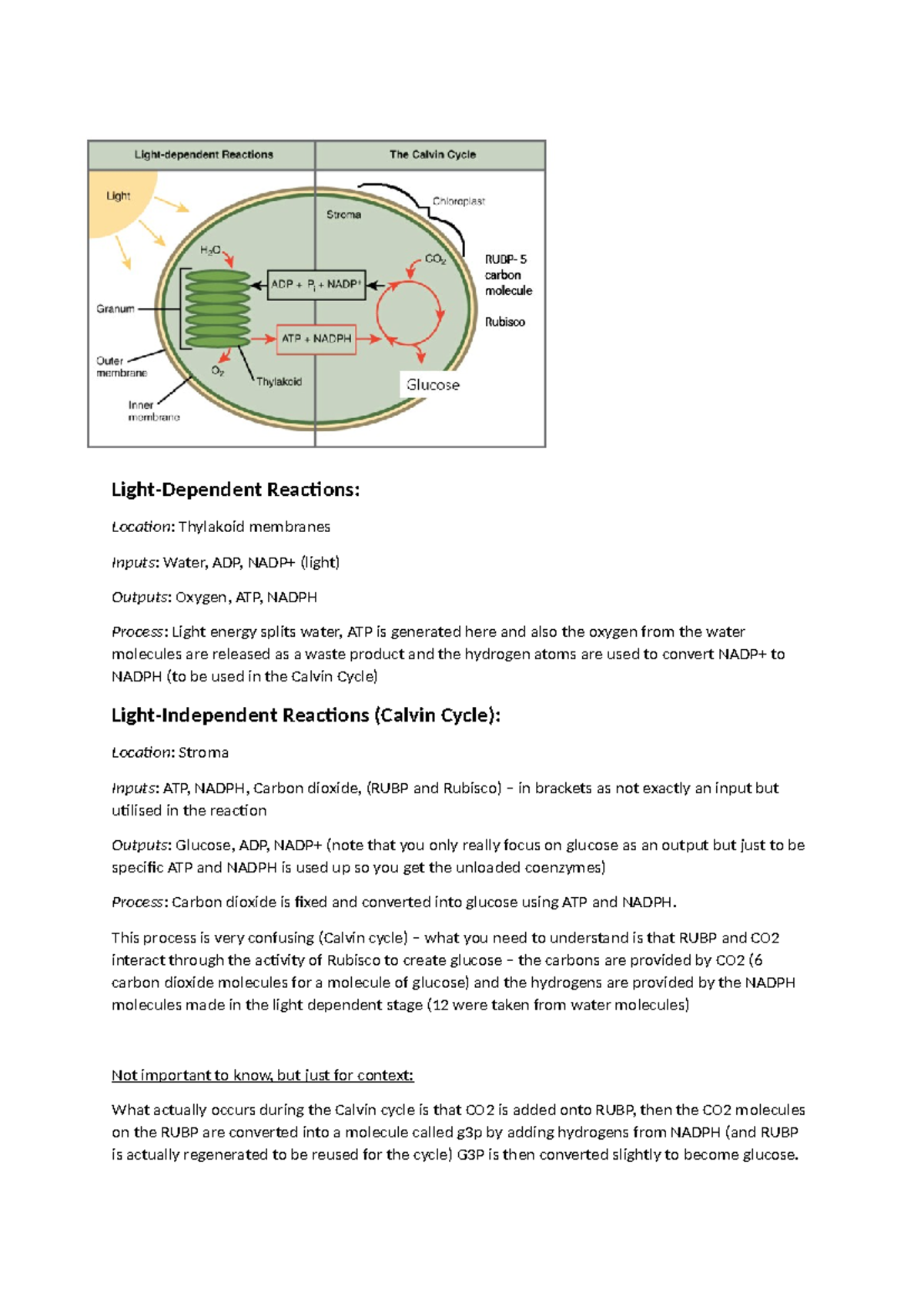

Photosynthesis operates in two interdependent stages—light-dependent reactions and the Calvin cycle (light-independent reactions)—each contributing uniquely to the overall output.The light-dependent reactions capture photon energy to produce ATP and NADPH, energy-rich molecules that power the dark stage. “These molecules are the financial force of photosynthesis,” observes Dr. Tran.

“They transfer energy and electrons needed to reduce CO₂ into sugars.” The Calvin cycle, occurring in the stroma of chloroplasts, then uses ATP and NADPH to fix carbon into glucose. “Though it consumes energy, this stage is the heart of biosynthesis,” explains Dr. Rodriguez.

“Without it, inorganic carbon remains trapped and unusable—photosynthesis loses its purpose.” The process’s efficiency varies across species. C₃ plants, the most common group, fix CO₂ directly via RuBisCO, but suffer from photorespiration under heat and drought. C₄ and CAM plants evolved adaptations to minimize waste, enhancing carbon fixation in challenging environments.

“This evolutionary refinement shows photosynthesis is far from static—it’s a dynamic, adaptive system,” says Dr. Tran, emphasizing that even minor changes in inputs like water availability or CO₂ concentration profoundly affect output quality and quantity. Globally, photosynthesis regulates Earth’s carbon cycle, sequestering gigatons of CO₂ annually and moderating climate.

It produces roughly 140 billion metric tons of organic carbon per year—enough to sustain life across ecosystems. “Every breath you take depends, directly or indirectly, on this underground factory,” notes a climate scientist. Moreover, the oxygen produced sustains aerobic life, enabling complex ecosystems from rainforests to deep oceans.

In urban landscapes and agricultural systems, photosynthesis directly influences food security. Crop yields are limited not just by genetics or irrigation, but by sunlight exposure, CO₂ availability, and water efficiency—all variables that define photosynthetic output. Innovations in crop breeding and controlled-environment agriculture aim to optimize these inputs, boosting productivity while conserving resources.

Beyond agriculture, the study of photosynthesis inspires technology. Scientists mimic its light-harvesting and energy-conversion mechanisms to develop solar fuels, artificial leaves, and sustainable chemical processes. “We’re not just learning from nature—we’re building the next generation of clean energy by reverse-engineering photosynthesis,” says Dr.

Rodriguez. In essence, photosynthesis is the quiet cornerstone of life. Its inputs—sunlight, CO₂, and water—are transformed into glucose and oxygen through a precisely orchestrated sequence, sustaining plants and, by extension, all aerobic organisms.

Understanding this intricate interplay of energy and matter underscores photography’s role not only as a biological process but as the life-support system for the planet.

Inputs: The Essential Raw Materials Powering Photosynthesis

The efficiency and feasibility of photosynthesis depend on three foundational inputs: light energy, carbon dioxide, and water. Each element fulfills a specific biochemical role, enabling plants to convert inorganic molecules into organic nutrients.Without their steady availability, the entire photosynthetic engine stalls, revealing the fragility and dependence of life’s energy cycle. Light Energy: The Driving Force Light serves as the primary energy source, initiating photosynthesis through light absorption by chlorophyll in specialized organelles called chloroplasts. Chlorophyll molecules capture photons, particularly in the blue (400–500 nm) and red (600–700 nm) wavelengths, exciting electrons to higher energy states.

This excitation triggers a chain of electron transfers within photosystems I and II, initiating the flow of energy that powers ATP and NADPH synthesis. “Photon capture is the first spike in the energy cascade,” explains Dr. Elena Rodriguez, a photosynthetic biochemist.

“Without sufficient light intensity or appropriate wavelengths, the electron transport chain cannot function efficiently, drastically reducing ATP and NADPH production—two critical outputs.” Light quality and duration profoundly influence photosynthetic rates; for example, shade-adapted plants evolve pigment variations to absorb scarce green light, while sun-loving species maximize absorption across broad spectra. Environmental factors like cloud cover, day length, and seasonal changes directly modulate the availability of this crucial input, shaping plant growth patterns globally. Carbon Dioxide: The Carbon Backbone CO₂ enters leaves through microscopic pores called stomata, regulated by guard cells responsive to environmental cues such as humidity and light.

Inside the Calvin cycle, this atmospheric CO₂ becomes the structural foundation for glucose synthesis, fulfilling its role as the primary carbon source. Each CO₂ molecule incorporated into the 3-carbon RuBP molecule enables the production of 1,5-carbon sugar (RuBP), ultimately leading to the

Related Post

IGood Insurance in Dubai: Your Complete Guide to Navigating Coverage with Confidence

Chasing Summer: Where the Heat Becomes Magic and Memories

Triple H Nick Khan Link up With Dana White

Michele Rice seven things to know about the daughter of Anne Rice and poet Stan Rice