The Glass Menagerie and the Fragility of Memory: Oscar Wingfield’s Haunting World of Fragments and Longings

The Glass Menagerie and the Fragility of Memory: Oscar Wingfield’s Haunting World of Fragments and Longings

In Tennessee Williams’ *The Glass Menagerie*, memory operates not as a steady beacon, but as a fragile, trembling veil—through which the protagonist, Tom Wingfield, peers into a past both tender and tormented. The play unfolds as a layered memoir, bound by the subjective lens of Tom’s retrospection, where reality blends with illusion, and the shards of glass figurines symbolize broken dreams, repressed guilt, and the inescapable weight of time. Using visual metaphors, performative rhythm, and interior soliloquies, Williams crafts a narrative that transcends mere storytelling—transforming memory itself into a living, breathing character.

What emerges is not a linear chronology, but a mosaic of longing, regret, and the desperate attempt to preserve what slips through fingertips like dust.

At the heart of the narrative lies the Wingfield household—a symbol of stasis and stagnation filtered through the lens of emotional withdrawal. Tom, the central narrator, lives in a cramped St.

Louis apartment, laboring in a dead-end role at a typewriter factory while harboring a poetic restlessness. His daily routine—transactional, mechanical—contrasts sharply with the fragile, luminous world of his mother, Amanda, who clings to faded Southern gentility, and his sister Laura, whose world revolves around an obsessive collection of glass animals. Each object, each whispered memory, reconstructs a past that is less historical record than emotional truth.

As Williams writes, “The past is not over. It’s not even past,” capturing the play’s central tension between what was and what endures.

The Glass Menagerie as a Mirror of Inner Fragmentation

Glass as Emotion: Fragility and Protective Shielding

Amanda’s glass menagerie—numbering over a hundred delicate figures—serves as the most potent symbol in the play, a tactile landscape of protection and denial. Each animal, hand-crafted or collected with ritual precision, represents a moment preserved, a fear managed, a vulnerability cushioned by artifice.The glass is mercury-thin; a crack sends ripples outward—much like trauma distorts perception and distorts relationships. Laura, who turns to glass as both refuge and prison, embodies this duality: her figurines shimmer like protective armor, but her muted voice and reclusive nature reveal a soul deeply wounded by shame and abandonment.

Tom’s Dual Identity: Spectator and Participant

Tom’s role as both narrator and workplace worker positions him as a liminal figure—caught between emotional withdrawal and a yearning for escape.His weary plea—“I’ve been a man, all right. A glass man—offstage and unseen”—cuts to the core of the play’s existential dilemma. He desires transformation, yet fears the instability of change.

As critic Harold Bloom observed, “Tom is not just a man trapped in time—he is time itself, suspended between the spectacle of his mother’s performative past and his own fragmented dream of catharsis.” His internal conflict reflects a universal struggle: how to reconcile identity with the forces that pull us apart.

The Architecture of Memory and Illusion

Tom’s narration is marked by deliberate artifice—each memory diligently constructed, embellished, or softened by hindsight. He romanticizes his childhood with a selective nostalgia, painting Amanda as a regal veronese and Laura as her ethereal twin.Such portrayals underscore the unreliability of memory: it is less about factual accuracy than emotional resonance. The play’s setting—a poorly lit apartment with cobweb-laden furniture—further blurs reality and dream. The windows gazed through, the flickering gas lamp, the echoing silence—these create an atmosphere where past and present bleed into one another.

“The menagerie… is not merely my escape—it is my life.” This statement, delivered with quiet resignation, encapsulates the paradox at the play’s core: the glass collection safeguards Laura but also traps her. It mirrors Tom’s own emotional imprisonment: while Laura retreats into her world, Tom stirs with a restless need to reach out, to connect, to transcend the fragile boundaries he seems to have built around himself. The menagerie, then, becomes both sanctuary and self-imposed exile.

Williams masterfully destabilizes temporal boundaries, weaving flashbacks, projections, and theatrical asides into a fluid continuum. This nonlinear structure reflects the mind’s own mechanisms—how memory fractures, loops, and sometimes reorders events in service of emotional survival. The play unfolds not like a film, but like a memory taking shape: impressionistic, nonlinear, and charged with psychological depth.

The Theater of Absence: Space and Silence as Narrative Forces

Staged in a thinly constructed apartment set, *The Glass Menagerie* turns physical space into a psychological landscape.The lack of outward movement emphasizes internal confinement. The gas lamp flickers like failing hope; the curtains—often drawn—conceal the harshness of the outside world. Amanda’s constant recounting of Southern gentility contrasts with the squalor of their reality, creating dramatic irony: the audience witnesses a world built on illusion, while the characters remain tragically unaware of their own disconnection.

“We are not in Kansas

Related Post

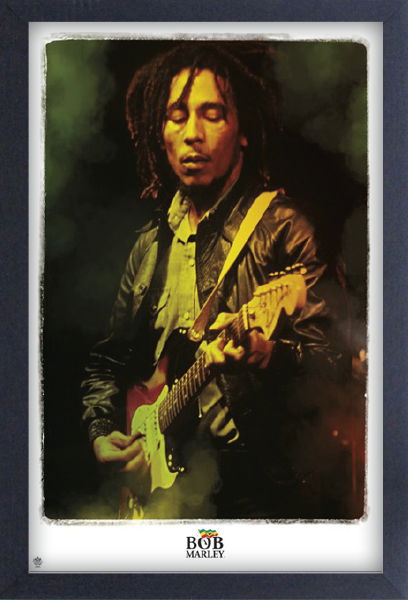

Pat Williams And Bob Marley: A Legendary Connection That Shaped Global Music and Culture

Unveiling the Truth: Is Ryan Paevey Married? Navigating the Actor's Private Life and Public Persona

Clash of Clans & Clash Royale: The Ultimate Crossover Guide for Clash Gamers

Unlock Enterprise-Grade AI Innovation with Freezerova’s Gitlab Powerhouse