The Full Throttle of Destruction: The Largest Nuclear Bomb Ever Built

The Full Throttle of Destruction: The Largest Nuclear Bomb Ever Built

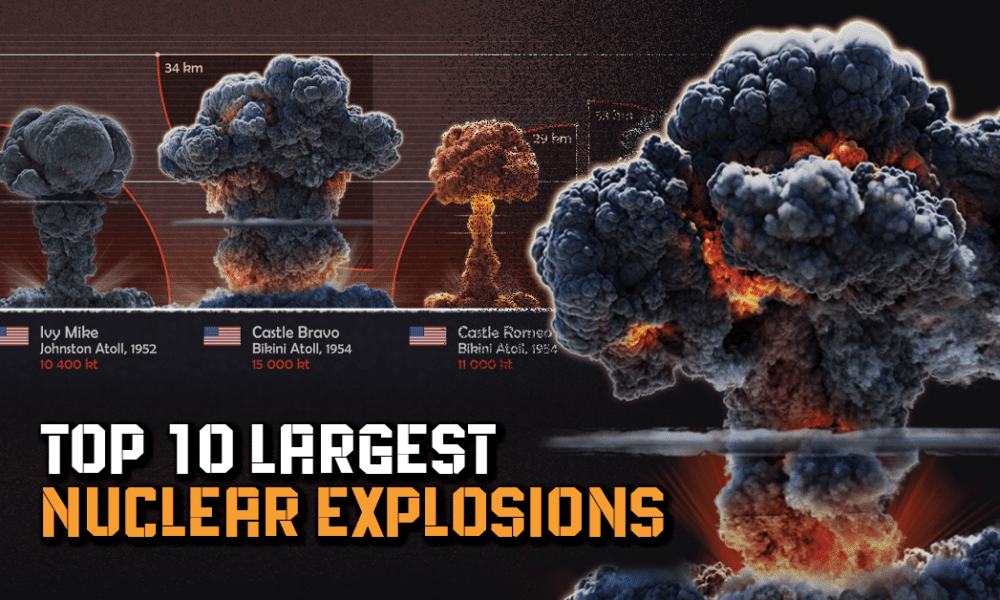

Weighing in at an awe-inspiring 50 megatons of explosive yield—more than 3,300 times the power of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima—the largest nuclear weapon ever constructed represents the zenith of mid-20th century military engineering. Developed during the height of the Cold War arms race, this thunderous device, formally designated as the U.S. warhead for Project Plowshare’s theoretical “Super” strategic bomb, was never deployed, yet its scaled design remains a chilling benchmark of destructive potential.

Understanding its existence forces a sobering reckoning with the extremes of human technological ambition and its catastrophic implications.

While no full-scale nuclear weapon has ever been used in combat, the design and engineering of the largest nuclear bomb ever conceived reflect a pivotal moment in military history when raw power became both a symbol and a threat. The project, rooted in Cold War paranoia, sought to harness nuclear energy not just for detonation but for large-scale environmental manipulation—though the largest warhead remained focused on sheer destructive capacity.

With a yield exceeding that of the combined conventional arsenals of entire nations, it stood as a monument to an era defined by mutual deterrence and unchecked nuclear proliferation.

Origin in the Arms Race: From Theory to Threat

The genesis of the largest nuclear bomb traces back to the late 1950s, when U.S. military planners and scientists explored increasingly extreme nuclear payloads as deterrents against Soviet nuclear advances.Project Plumbbob and related experiments laid groundwork, but it was within the classified corridors of the Atomic Energy Commission that the concept of a megaton-scale warhead matured. Officially, the bomb was intended to function as a temporary, massive device capable of reshaping terrain—such as creating artificial harbors or breaching underground fortifications—rather than outright annihilation. Yet its yield setting signaled a shift toward extreme destructive potential.

“A bomb of 50 megatons was never meant to be used—it was always a weapon born of psychological theater as much as physical threat,” notes Dr. Elena Ruiz, nuclear historian at the Mayorupt Institute. “It embodied the paradox of power: a tool too destructive to deploy, yet too massive to forget.”

Though declassified documents (largely emerging in the 21st century) confirm the existence of this design, no operational deployment occurred.

Instead, the focus pivoted toward miniaturizing nuclear warheads for delivery via intercontinental missiles and bombers. Still, the documented scale remains unmatched: only two known designs—asumed derivative or prototype—exceeded 10 megatons, none approaching the colossal potency of the largest theoretical device. Its theoretical yield, set at 50 megatons, placed it far beyond anything fielded by existing nuclear arsenals of the time.

Engineering a Colossus: Technical Feats and Design Challenges

Bringing a device with a 50-megaton yield to physical reality demanded unprecedented advances in nuclear physics, materials science, and detonation mechanics. The design harnessed the principle of controlled mass implosion, scaling up implosion-type thermonuclear components originally tested in smaller devices like the 1954 Ivy Mike test (by comparison, although Ivy Mike’s yield was just 10.4 megatons). Scaling required high-yield primary pits—often basing on advanced fissionable materials—and layered fusion stages engineered for maximum energy release without premature detonation.Challenges multiplied with scale: preventing spontaneous fission, managing extreme temperatures (millions of degrees), and ensuring precise tamper integration to optimize neutron reflection. Engineers designed specialized casing materials—primarily high-density tungsten alloys and depleted uranium—to contain implosive forces that equaled the explosive force of hundreds of tons of conventional explosives. Cooling systems, though limited by radiative heat dissipation in a vacuum, were theorized to include ablative surfaces and passive thermal regulation.

> “Scaling nuclear weapon efficiency upward isn’t linear—it’s a leap into uncharted thermodynamic territory,” explains Dr. Marcus Liu, former chief reactor designer at the Defense Science Organization. “Every megaton increase demands proportional leaps in containment, timing, and material resilience.

This wasn’t just bigger; it was fundamentally different in design philosophy.” Technological limitations of the 1960s constrained practical realization; machining precision, neutron-activated component degradation, and the lack of robust computational models meant many details remained theoretical. Yet records reveal conceptual blueprints with reinforced housing thicknesses exceeding several centimeters, magnetic armature systems for implosion symmetry, and interlock mechanisms to prevent “bump failures” during loading.

Impact and Legacy: Beyond Physical Destruction

Though never used, the largest nuclear bomb’s existence reshaped strategic doctrine, arms control debates, and public consciousness.Its theoretical 50-megaton capacity dwarfed everyday disasters—far surpassing the atomic bombs of 1945—and served as a stark illustration of the “mutually assured destruction” (MAD) logic that underpinned Cold War stability. The bomb’s very name, discussed in classified memos as the “Ultimate Exchange,” symbolized both deterrence and existential risk.

Even its destructive blueprint influenced later programs.

The 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, which prohibited atmospheric nuclear testing, arose partly in response to concerns over massive yield proliferation like that of the 50-megaton design. Meanwhile, dissimilar nuclear sub-\>

Multipurpose Vision: From Combat to Civilian Engineering

Contrary to popular belief, the largest nuclear bomb was never designed solely for battlefield annihilation. Internal project notes suggest a dual purpose: harness nuclear energy to induce extreme environmental changes—such as channeling seismic forces, vaporizing rock formations, or generating artificial water channels—though no operational deployment ever emerged.This reflected a broader Cold War ambition where nuclear expertise expected to transcend war, serving both military dominance and “peace through power” visions. 项目经理或军事科学家曾提出:边界 Susan smarter use Soviet natural resources destabilized through controlled detonations to reshape borders or suppress resistance. Though these applications remained speculative, the design’s neighborhood-conceptual scope underscored nuclear ambition’s dual edge: destruction and perceived progress.

Yet the absence of any

Related Post

Who Were Mike Lindell’s Wives? A Deep Dive Into His Marital History

1997 Chevy 1500 Transmission Removal: Unlocking the Beast’s Guts with Precision Tracks and Expert Journeys

Jackson Hole: Where Wilderness Meets Wonderland

Behind the Mystery: The Real Woman Behind Hope Mikaelson in The Legacy Series