Sepsis Defined: The Life-Threatening Response That Demands Immediate Recognition

Sepsis Defined: The Life-Threatening Response That Demands Immediate Recognition

Sepsis is not merely an infection—it is a systemic, life-or-death cascade of inflammatory responses that disrupts normal physiological function across the body. When the immune system overreacts to infection, triggering widespread inflammation, sepsis sets in, threatening organ failure and death within hours if untreated. According to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign, more than 11 million adults in the United States alone suffer from sepsis each year, with nearly 50% of patients requiring intensive care—underscoring its global clinical urgency.

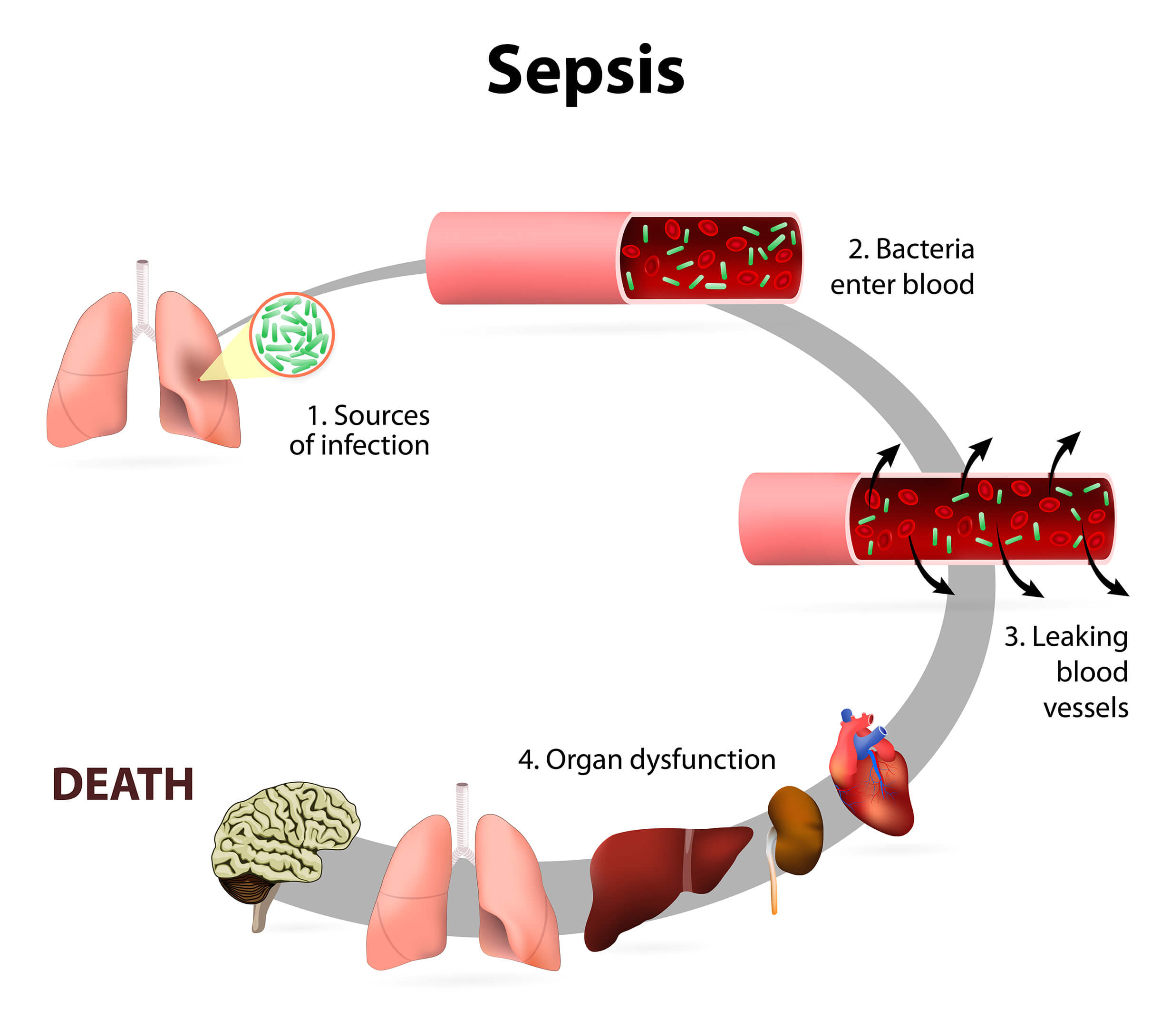

Unlike localized infection, sepsis reconfigures the body’s internal balance, turning defense into destruction. Defined medically as a “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection,” sepsis arises when the body’s attempt to fight pathogens results in collateral damage. The infection—whether bacterial, viral, fungal, or even less common sources—activates an overwhelming immune reaction.

Key changes occur at the cellular level: white blood cells release toxic inflammatory mediators, endothelial cells lining blood vessels release cytokines, and microthrombi form in small vessels, reducing oxygen delivery. This cascade impairs vital organs including the lungs, kidneys, liver, and brain. Understanding the Pathophysiology: How Sepsis Hijacks the Body At its core, sepsis disrupts homeostasis through a fragile balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory processes.

Initially, the immune system amplifies inflammation via molecules like tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), aiming to eliminate microbes. However, unchecked, these signals spill into the bloodstream, causing widespread vasodilation, capillary leakage, and blood clot formation. The result is poor perfusion—tissues starved of oxygen and nutrients—leading to cellular starvation and death.

Key physiological consequences include: - **Systemic inflammation**: Triggering fever, tachycardia, and elevated respiratory rate, often misread as flu or pneumonia. - **Microcirculatory failure**: Reduced blood flow to organs despite normal or elevated pressures on large vessels, visible under microscopic analysis. - **Coagulation dysfunction**: Activation of clotting systems promotes microthrombi, obstructing blood flow, while natural anticoagulants fail.

- **Acute organ dysfunction**: Marked by rising lactate levels, altered mental status, oliguria (reduced urine output), and metabolic acidosis. As Dr. Steven Branch, a critical care expert, explains: “Sepsis isn’t just an infection—it’s a storm of biological misfire that, if left unchecked, resets the entire body’s regulatory systems into chaos.” Recognition and the Golden Hour: Time is Critical Early identification of sepsis is paramount and hinges on timely recognition of classic clinical signs.

The quick recognition protocol, widely adopted by emergency and intensive care teams, centers on the “Sepsis Six”: a bundle of initial interventions designed to stabilize the patient and halt progression. These include administering intravenous fluids, initiating antibiotics within the first hour, identifying the source of infection, measuring lactate levels, providing oxygen, and correcting acidosis. The “Surviving Sepsis Campaign” defines severe sepsis as infection with organ dysfunction and sepsis with hypotension—indicated by systolic blood pressure below 100 mmHg or a dangerous drop in mean arterial pressure (MAP).

Without rapid intervention, the risk of multi-organ failure soars: within hours, mitochondrial impairment halts cellular respiration, and cell death accelerates. Studies show that each delayed hour without treatment reduces survival by approximately 7–10%. Recognizing symptoms early is challenging; sepsis presents variably, especially in vulnerable populations such as the elderly, immunocompromised, or those with chronic conditions.

Common but nonspecific signs include fever above 380°F (38.3°C), elevated heart rate, rapid breathing, confusion, and stark changes in urine output. Pediatric sepsis, for example, may manifest as irritability, a bulging soft spot on the head, or a rash—pert contraire to adult patterns. Populations at Higher Risk: Who Faces the Greatest Threat? Certain groups confront an elevated risk of severe sepsis, necessitating vigilant monitoring.

These include: - **Elderly patients**, particularly those over 65, whose immune systems often underreact initially while inflammation overreacts—a phenomenon known as immunosenescence. - **Individuals with chronic conditions** such as diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or malignancy, where baseline organ reserve is diminished. - **Neonates and infants**, whose immune systems are immature and harder to assess clinically.

- **Patients with prolonged hospital stays or invasive devices**, including ventilators or central lines, which increase exposure to pathogens. - **Those recovering from major surgery, trauma, or prolonged ICU stays**, where tissue damage and immunosuppression create fertile ground. Age and underlying health profoundly shape the body’s resilience.

“The older you are, the more fragile your regulatory mechanisms become,” notes Dr. Monica Patel, a hospital epidemiologist. “Even a minor infection can spiral into life-threatening cascades.” Diagnosis: Marching to Lab and Clinical Clues Diagnosing sepsis combines clinical observation with biomarkers and laboratory data, guided by standardized criteria.

The textbook definition—systemic response to infection with organ dysfunction—guides assessment. Current diagnostic tools emphasize early detection through symptom triage and objective measures. The **Sepsis-3 diagnostic criteria**, adopted widely since 2016, expand on earlier definitions by introducing “sequential organ failure assessment” (SOFA) scores to quantify organ dysfunction.

A SOFA score increase of ≥2 in two or more organ systems confirms severe sepsis or septic shock, a more dangerous state where vasopressors are required. Blood cultures remain critical but are often negative at onset—up to 30% of early sepsis cases yield no pathogen detection, stressing the need for clinical judgment and serial reassessment. Lactate levels serve as a vital prognostic marker: levels ≥4 mmol/L typically signal tissue hypoperfusion and correlate with worse outcomes.

Continuous monitoring, including hemodynamic status and urine output tracking, helps detect deterioration before assets fail. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is emerging as a rapid tool, helping assess heart function, detect fluid overload, and guide fluid resuscitation—bridging immediate clinical insight with diagnostic precision. Treatment: A Multidimensional Approach to Rewrite the Outcome Narrative Treating sepsis demands speed, precision, and coordinated care across multiple disciplines—from emergency response to intensive medicine.

The first 6 hours are decisive, demanding integration of pharmacologic, hemodynamic, respiratory, and source-targeted interventions. **Immediate interventions include:** - **Fluid resuscitation**: Initial boluses of crystalloids restore intravascular volume and perfusion. Guidelines recommend up to 30 mL/kg, though overload risk demands cautious titration.

- **Broad-spectrum antibiotics**: Initiated within one hour, tailored later via culture and sensitivity. Timing correlates strongly with survival—delay risks multidrug-resistant infections and worsening organ damage. - **Source control**: Draining abscesses, removing infected devices, or debriding necrotic tissue halts infection spread.

Missing this step, treatment remains palliative. - **Oxygen and ventilation support**: Ensuring adequate tissue oxygenation, sometimes requiring noninvasive or mechanical ventilation. - **Vasopressor therapy**: For persistent hypotension, medications like norepinephrine restore effective circulating volume and stabilize organ perfusion.

- **Renal replacement therapy**: In cases of severe acute kidney injury, dialysis supports metabolic balance. Beyond stabilization, post-acute recovery is often overlooked. Survivors face prolonged immunosuppression, muscle atrophy, cognitive decline, and psychological trauma—collectively termed post-sepsis syndrome.

“Sepsis leaves scars far beyond the initial infection,” cautions Dr. Rajiv Mehta, a critical care specialist. “Rehabilitation must be as rigorous as initial resuscitation.” The Urgency Remains: Why Awareness Drives Survival Sepsis continues to rank among medicine’s greatest silent killers—not due to invisibility, but underestimation.

Its symptoms mimic common illnesses, leading to delayed diagnosis, especially in vulnerable populations. Yet, with proper recognition, timely antibiotics, and proactive supportive care, survival rates improve dramatically. Patients and clinicians alike must remain alert.

Recognizing that “sepsis is not one disease but a dynamic process” empowers better response. A fever spike without clear cause in an elderly person with diabetes may be sepsis. A confusing patient in ICU with elevated lactate needs urgent reassessment, not reassignment.

The fight against sepsis is as much about education as therapy. Public awareness campaigns, provider checklists, and early warning systems are redefining care pathways worldwide. Every hour saved translates not just in longer lives, but in quality of life reclaimed.

In the grand arc of medical advance, sepsis remains a formidable foe—but with precision, urgency, and collective vigilance, it need not remain a silent threat. Understanding its definition, recognizing its signals, and advancing treatment forms the cornerstone of defeating one of the modern era’s most pressing health crises.

Related Post

Sepsis Defined: Unraveling the Critical Illness Every Healthcare Professional Must Know

Unlocking the Mystery: How Kennedy Ulcer Pictures Shaped Medical Awareness

Fly Like An Eagle Lyrics Meaning And Youtube Performances

Top English Universities in Japan: Your Ultimate Guide to Global Education in the Land of Tradition