Revolution Redefined: How AP World History Frames Intervention as a Global Catalyst for Change

Revolution Redefined: How AP World History Frames Intervention as a Global Catalyst for Change

When nations intervene—whether through military force, economic pressure, or diplomatic coercion—their actions reverberate far beyond borders, reshaping political systems, economies, and societies for generations. In AP World History, “intervention” is not merely a tactic but a transformative force, deeply embedded in historical analysis as a concept that alters trajectories on local and global scales. Defined through rigorous scholarship, intervention involves external involvement in a state’s internal affairs, often justified by moral, strategic, or economic imperatives.

The AP framework emphasizes how interventions ignite cascading effects—sparking resistance, accelerating reform, or entrenching instability—depending on context, scale, and intent.

Central to understanding intervention in world history is recognizing its multidimensional nature. According to AP Warfare and Intervention standards, interventions manifest across military, political, economic, and ideological domains, leaving tangible and intangible traces.

Military interventions, such as imperial invasions or modern peace enforcement, often trigger immediate upheaval—from regime change to the collapse of traditional governance structures. Meanwhile, economic interventions—ranging from trade sanctions to structural adjustment programs—reshape national economies by altering resource flows, production models, and social inequalities. Perhaps most subtly, ideological interventions—driven by propaganda, religion, or education—can redefine cultural identities and long-term political orientations.

Defining intervention requires examining intent, power dynamics, and historical context.

The AP definition highlights three critical criteria: external agency (involvement by a non-domestic actor), purposeful action (deliberate influence rather than coincidence), and measurable impact (lasting change in political or social systems). For example, during the Spanish-American War (1898), the U.S. intervention in Cuba was framed as a humanitarian effort to end Spanish colonialism, yet its aftermath enabled American economic dominance, fundamentally transforming Cuba’s political economy.

This illustrates the concept that interventions are rarely one-directional—external actors impose influence, but local responses often redirect outcomes in unpredictable ways.

The Evolution of Intervention from Colonial Enclosure to Cold War Geopolitics

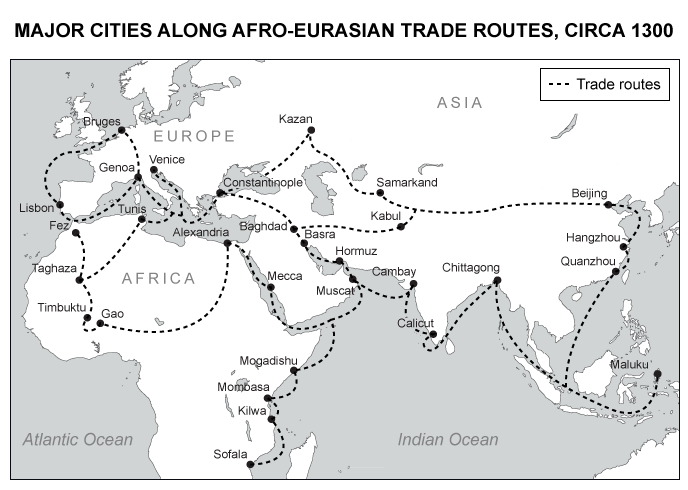

The historical trajectory of intervention reveals a shifting rationale and methodology. In the early modern period, European powers justified territorial intervention under the guise of civilizing missions or economic extraction—what historians now term “salutary imperialism.” Interventions in Africa during the Scramble for Africa (1880s–1914) exemplify this era: territorial annexations were rationalized as Cold War precursors, with forces dismantling indigenous governance and installing extractive regimes designed to serve European industrial needs. The Berlin Conference (1884–85), often studied in AP curricula, formalized this interventionist logic through legal frameworks that carved the continent into controlled zones of influence, disregarding local ethnic and political realities.By the 20th century, intervention evolved amid ideological conflict. The Cold War transformed external involvement into a global contest between capitalist and communist blocs. U.S.

interventions in Latin America—such as the 1954 Guatemalan coup or the 1989 Panama invasion—were framed as anti-communist measures but frequently undermined democratic development, fostering long-term instability. Meanwhile, Soviet interventions—like the 1979 Afghan War—promised liberation but catalyzed decades of resistance and radicalization. As historian Melvyn Leffler notes, “intervention is not just action; it is a catalyst for unintended consequences.” Economic interventions also grew more sophisticated, with structural adjustment programs imposed by institutions like the IMF altering development paths in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America in the 1980s and 1990s, often deepening inequality despite promises of reform.

Notable modern cases reinforce the AP definition’s analytical rigor. In Iraq (2003), the U.S.-led invasion, justified initially by weapons proliferation claims, triggered sectarian violence, state collapse, and the rise of extremist groups—demonstrating how military intervention can unravel complex social fabrics. Conversely, NATO’s 1999 intervention in Kosovo, though controversial, halted ethnic cleansing and contributed to regional stabilization, illustrating intervention’s potential when aligned with humanitarian imperatives.

These examples underscore a recurring theme: intervention’s legacy depends less on initial intent than on implementation, local agency, and long-term commitment. Defining intervention today demands recognizing its dual capacity: as both a tool of power and a transformer of political reality.

Defining Intervention’s Impact: From State Collapse to Reform Movements

AP World History treats intervention as a pivotal variable in world history, shaping state formation, political ideology, and social movements. Its impact unfolds across multiple domains, each revealing different layers of historical consequence.Military interventions often redraw borders and dismantle regimes, but rarely produce stable successors. The 1917 Russian Revolution, catalyzed indirectly by World War I interventions and foreign policy pressures, dismantled the Romanov dynasty and established a new revolutionary state, fundamentally altering global communism. Similarly, U.S.

involvement in Vietnam (1955–75)iened a protracted war that, despite tactical military superiority, resulted in political collapse and regional realignment. These conflicts highlight intervention’s paradox: overwhelming force can fail to secure lasting control, especially against resilient local movements. Economic interventions, particularly structural adjustment programs, reshape national economies by imposing market liberalization, privatization, and fiscal austerity.

From the IMF’s role in 1980s Zambia to World Bank mandates in post-Soviet Russia, such policies often eroded public services and exacerbated poverty, provoking widespread protests and political unrest. Yet, they also stimulated new economic actors and global integration—illustrating intervention’s dual role in both constraining and enabling development. Ideological interventions leave enduring cultural imprints.

The spread of democracy promotion since the Cold War, evident in U.S. and EU foreign policy, exemplifies how external influence can reshape governance norms. Yet indigenous responses—from adaptive reforms to authoritarian resistance—reveal that intervention rarely produces uniform outcomes.

Instead, it interacts dynamically with local contexts, generating unpredicted social, cultural, and political transformations.

Across these varied domains, AP interventions are defined not by intention alone, but by tangible, lasting change—whether coercive, adaptive, or transformative. The recognized necessity of intent, agency, and impact ensures rigorous analysis, enabling historians to assess interventions as historical forces rather than incidental events.

Defining intervention thus requires a balanced lens: one that acknowledges power imbalances while recognizing the capacity for local actors to redefine outcomes.

The Imperative of Contextual Understanding

Intervention remains a cornerstone of global history, a complex and often destabilizing force that presidents, statesmen, and revolutions alike have wielded with profound consequences. The AP World History definition provides a structured way to analyze these actions—not as black-and-white judgments of right or wrong, but as multifaceted interventions embedded in broader historical currents. Whether military, economic, or ideological, each instance demands scrutiny of motives, mechanisms, and outcomes.In understanding intervention, historians illuminate not only the mechanisms of power but also the resilience of societies to shape their own destinies amid external pressures. This lens transforms intervention from a mere historical event into a critical lens for interpreting how global systems evolve—and struggle.