Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes Revealed: The Unexpected Overlap in the Tree of Life

Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes Revealed: The Unexpected Overlap in the Tree of Life

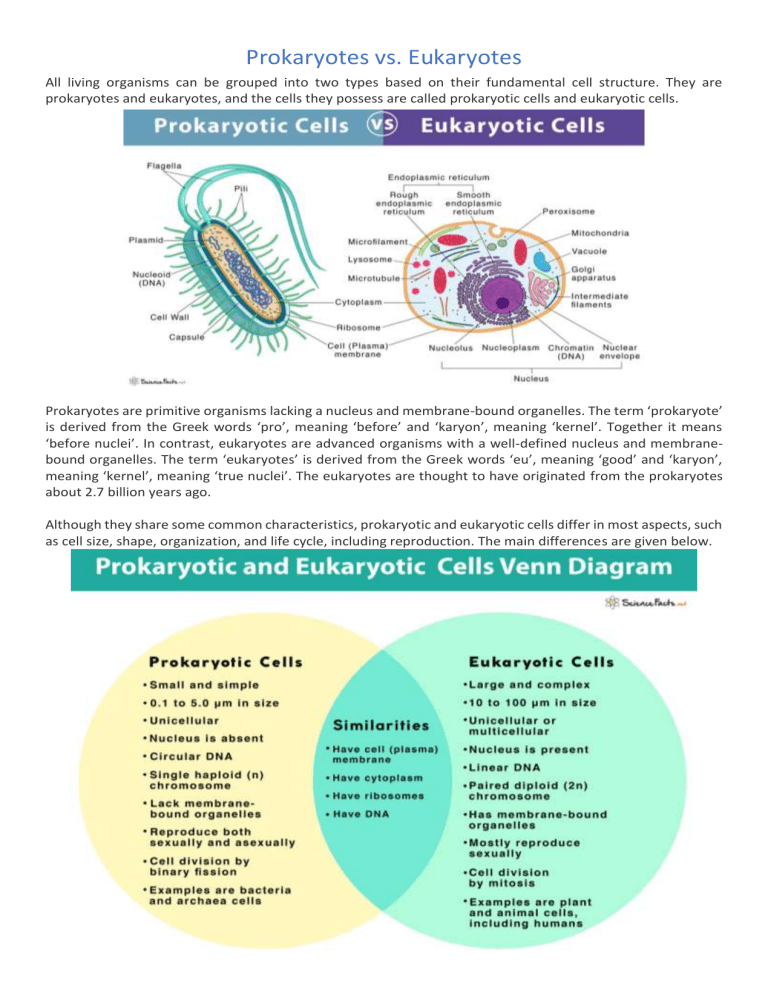

At the heart of biological classification lies a profound truth: life, in all its complexity, is shaped by two fundamental cellular architectures—prokaryotes and eukaryotes—each defined by distinct structural and functional traits. Yet beneath the surface of these categorical boundaries lies a subtle, often overlooked convergence: a shared geometric blueprint captured in the elegant Venn diagram that maps their commonalities and differences. This visual framework illuminates not just distinction, but also the evolutionary dialogue between simplicity and complexity.

The Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes Venn Diagram is more than a passive illustration; it is a dynamic cartography of life’s foundational design, revealing how early cellular life diversified while preserving essential biochemical and genetic principles.

Central to cellular biology is understanding how cells organize their internal architecture—where prokaryotes, with their streamlined, minimally structured cells, coexist with eukaryotes, whose elaborate internal compartments enable advanced functionality. Prokaryotes—dominated by bacteria and archaea—possess no nucleus or membrane-bound organelles, relying instead on a single circular chromosome floating freely in the cytoplasm.

Their cellular economy reflects efficiency: genes are transcribed and translated with rapid coordination, encased in a single, flexible boundary—the plasma membrane. In contrast, eukaryotes, which include plants, animals, fungi, and protists, encapsulate their genetic material within a nuclear envelope, enabling intricate regulation and spatial organization. Organelles such as mitochondria, Golgi apparatus, and endoplasmic reticulum create a compartmentalized environment, allowing for specialized metabolic pathways and developmental complexity.

The Mapping of Shared Foundations

Despite their structural disparities, prokaryotes and eukaryotes share deep biochemical roots that bind them at the molecular level.Both cell types deploy DNA as the carrier of hereditary information, proteins as the primary functional molecules, and ribosomes—though differently shaped—as the sites of translation. “The ribosome, a molecular machine built from ribosomal RNA and proteins, exists in both domains,” explains molecular biologist Dr. Elena Marquez, “and its core structure reflects ancient evolutionary heritage.”

This shared reliance on DNA repair enzymes, transcription factors, and energy-producing pathways like glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation underscores a profound continuity.

“These conserved systems are not mere accidents,” notes Michael Chen, a professor of evolutionary genomics. “They represent gene circuits refined over billions of years—some predating the very split between prokaryotic and eukaryotic lineages.”

Further evidence of shared origins lies in the phospholipid bilayer that defines cell membranes in both domains. Although propelled by different evolutionary pressures—prokaryotes optimizing for rapid adaptation, eukaryotes for structural stability—the fundamental architecture remains identical.

This membrane-based boundary, dotted with transport proteins, enables selective permeability and signaling across both cell types. Superficially, prokaryotes might appear primitive, but their membrane systems rival eukaryotic sophistication in efficiency, especially in nutrient uptake and response to environmental shifts.

Structural Minimalism vs.

Molecular Multiplicity The most striking division—and surprising overlap—between prokaryotes and eukaryotes lies in cellular compartmentalization. Prokaryotes strip cells down to essentiality: no nucleus, no specialized organelles, no cytoskeleton beyond occasional ftsZ-based minimal frameworks. Their DNA floats indistinct from cytoplasm, proteins diffuse freely, and metabolism unfolds in a single, fluid environment.

Eukaryotes, by contrast, embrace architectural diversity: a dynamic cytoskeleton governs movement, vesicular trafficking enables spatially segregated processes, and membrane-bound compartments insulate and specialize functions. Yet even here, stealth parallels emerge. For instance, archaeal cells—often misunderstood as “truly prokaryotic”—display eukaryote-like features such as introns and histone-like DNA packaging, blurring traditional boundaries.

Consider the ribosome again: while prokaryotic ribosomes (70S) differ in size and protein composition from eukaryotic ones (80S), their core role remains unchanged—deciphering mRNA into protein. This molecular conservation, despite divergent cellular designs, reflects a unifying principle in biology: form follows function, but function preserves evolutionary echoes. “The Venn diagram captures more than division,” observes Dr.

Lena Torres, a cell evolution specialist. “It highlights functional convergence—how life solves similar problems in radically different forms.”

Evolutionary Crossroads: Where the Path Diverged and Converged The split between prokaryotes and eukaryotes, estimated around 2 to 2.5 billion years ago, marked a pivotal chapter in biosphere history. Prokaryotes, masters of early Earth’s environments, colonized nearly every niche—from hydrothermal vents to polar ice.

Eukaryotes emerged from a prokaryotic ancestor through endosymbiosis: mitochondria and chloroplasts originated as free-living bacteria engulfed by a host cell, a partnership that unlocked energy efficiency and complexity. This merger remains the cornerstone of eukaryotic diversity today.

Yet, the Venn diagram persists beyond origin: even today, prokaryotes interact symbiotically with eukaryotes, from gut microbiota aiding digestion to nitrogen-fixing bacteria sustaining plant life.

“These relationships are not anomalies—they reinforce the diagram’s significance,” says Chen. “Life thrives not just through competition, but through integration.”

Microscopic Architecture, Macroscopic Impact The Venn diagram’s dual nature—delineating difference while revealing shared foundations—resonates across ecological and biomedical domains. In evolutionary biology, it underscores that complexity does not evolve in isolation; rather, it builds on a toolkit coded by ancestral prokaryotic life.

In medicine, understanding this overlap informs antibiotic development, antifungal strategies, and synthetic biology. “When designing drugs targeting bacterial cells,” explains Marquez, “we must respect their fundamental machinery—like the prokaryotic ribosome—without disrupting human eukaryotic cells.”

Moreover, in astrobiology, the Venn diagram serves as a blueprint for detecting extraterrestrial life: systems with DNA, membranes, and metabolic circuits—whether archaeal or eukaryotic—remain the universal signatures of life as we know it.

In every bacterium’s compact core and every eukaryotic organelle’s refined specialization, life’s story unfolds as a symphony of unity and variation.

The Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes Venn Diagram is not a static chart but a living document—evolving with every genomic discovery, every cellular mechanism uncovered. It captures the paradox at nature’s heart: within cellular minutiae, life reveals deep coherence, and in microbial simplicity, the roots of complex walks. This enduring balance between distinction and interconnection ensures that the map of cell biology remains as vital and revealing as the cells it depicts.

Understanding life’s architecture through this lens demands both precision and wonder.

It challenges us to see beyond rigid classifications, embracing a continuum where prokaryotes and eukaryotes stand not as opposites, but as cousins shaped by shared ancestry and adaptive genius. As science probes deeper into cellular design, the Venn diagram remains a powerful guide—illuminating the intricate dance of origin, evolution, and integration that defines life itself.