Periodic Table Ionic Charges: The Atomic Wisdom Behind Bonding and Reactivity

Periodic Table Ionic Charges: The Atomic Wisdom Behind Bonding and Reactivity

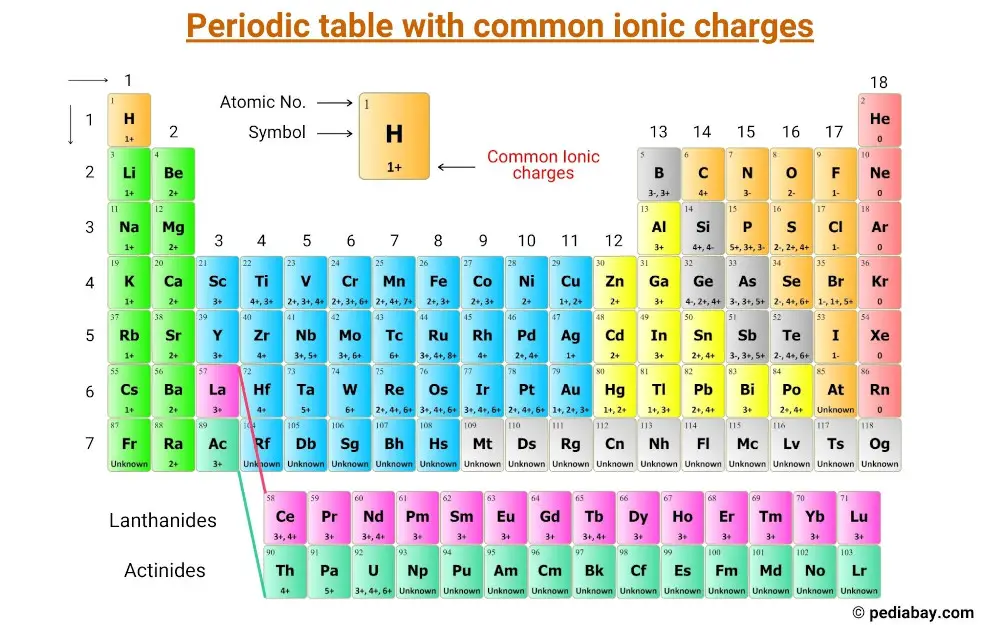

Across the 118 known elements, a silent logic governs the formation of compounds—governed not by randomness, but by the precise ionic charges dictated by their position on the Periodic Table. These charges, rooted in electron configuration and valence stability, serve as the fundamental currency of chemical behavior, dictating how atoms attract, donate, or share electrons. From the explosive reactivity of alkali metals with responsibly charged ions to the measured precision of noble gases, ionic charge patterns enable predictability in chemistry’s most vital transformations.

Understanding this system unlocks the ability to decode molecular architecture, anticipate reactivity, and design materials with targeted properties. The essence of ionic charge lies in the pursuit of electronic stability. Atoms gain or lose electrons to achieve a full outer shell—mimicking the electron configuration of noble gases.

When an atom donates electrons, it becomes positively charged; when it gains electrons, a negative charge emerges. This charge difference forms ionic bonds, the glue holding compounds like sodium chloride together. Yet the progression of charge across the Periodic Table follows a clear trend: ionic charge magnitude intensifies toward the right and top of the table, with main-group metals stabilizing as +1 or +2, and nonmetals achieving near-full electron acceptance through strong negative charges.

The Group Trends: How Position Dictates Charge Behavior

Across each period, charge patterns reveal structural consistency. In Group 1—alkali metals—electrons occupy the simplest configure, making ionization effortless. Lithium, sodium, potassium, rubidium, cesium, and francium all shed a single electron to reach a +1 charge, each stabilizing by attaining a noble gas electron configuration.This +1 charge remains constant, reflecting minimal electron-electron repulsion and low effective nuclear charge. Moving left to the alkaline earth metals in Group 2—beryllium, magnesium, calcium, strontium, barium, and radium—ionization becomes progressively harder, yet the +2 charge remains unbroken. These divalent ions donate two electrons with comparable ease, seeking octet completion.

Though nuclear charge increases, the addition of electrons in successive shells preserves the +2 charge, underscoring how orbital size and electron shielding play critical roles in charge stability. The p-block introduces complexity. Nonmetals in Groups 15–17 diverge sharply: Group 15 elements like nitrogen and phosphorus gain three electrons to achieve a -3 charge, achieving full valence shells; Group 16 elements (oxygen, sulfur) gain two electrons for a -2 charge.

Groups 17 (halogens) withdraw one electron to drop to a -1 charge. These assigned charges reflect the atoms’ electron affinity and the energetic cost of either gaining or losing electrons. Transition metals, occupying the d-block, exhibit variable charges—+1, +2, often +3, depending on coordination and oxidation state.

This variability stems from loosely held d-electrons, allowing robbery of stability across multiple charge levels. Unlike main-group elements, transition metals do not follow simple, fixed charges, rendering their chemistry both rich and challenging.

Isoelectronic Series and Effective Charge Variations

Even within diverse structures, ionic charge stability emerges through isoelectronic series—atoms or ions sharing the same number of electrons but differing nuclear charges.A classic example is the oxide ion (O²⁻), fluoride (F⁻), and nitrate (NO₃⁻)’s relatives. With ten valence electrons, their charge balances differ based on nuclear charge: O²⁻ carries a -2 charge due to a +8 nucleus pulling two electrons more forcefully than a +7 from F⁻ or a +5 from NO₃⁻. This illustrates how ionic charge reflects not just electron count, but nuclear attractiveness.

The relationship between nuclear charge and ionic stability reveals a key principle: as nuclear charge increases across a period, the ability to stabilize a given electron count strengthens. Group 2 elements transition from +2 to +1 oxidation states (e.g., Mg²⁺ to Mn²⁺) not because of electron instability, but because increased positive charge in heavier ions enhances electron affinity and ion formation efficiency.

Noble Gases: The Exceptions That Define Charge Norms

Within the Periodic Table’s iconic group 18, noble gases stand apart.Chemically inert, they resist electron transfer due to fully filled shells, finding no thermodynamic incentive to form ions. Unlike halogens or alkali metals, noble gases do not exhibit stable ionic charges—chetions are effectively nonexistent in nature. Yet their near-zero ionic charge contrasts sharply with their neighbors, highlighting how electronic closure underpins chemical inactivity.

This absence, however, deepens scientific understanding. It validates that ionic charge arises not from electron count alone, but from the thermodynamic drive toward stability. Noble gases confirm that stability—not reactivity—governs charge assignment.

Applications: From Fertilizer to Fireworks — Charge Behavior in Real-World Chemistry

The predictive power of ionic charges drives countless applications. In agriculture, ammonium (NH₄⁺) and phosphate (PO₄³⁻) ions—charged accurately by nitrogen (+3 or +5, phosphorus -3)—are foundational to fertilizers, enabling efficient nutrient delivery to plants. Similarly, sodium chloride (NaCl) relies on +1 and -1 charges to form a stable lattice critical for both biological fluid balance and industrial durability.In advanced materials, lead(II) oxide (PbO²⁻) with +2 oxygen and heavy lead charge contributes to superconductors and radiation shielding. The charge balance in such compounds ensures atomic packing precision, determining mechanical and electrical properties. In energy storage, lithium-ion batteries exploit Li⁺’s +1 charge for reversible intercalation in graphite anodes—enabling portable power and electric mobility.

Even in combustion chemistry, ionic charges define reactivity. Alkali metal salts ignite more readily due to +1 charge-assisted electron donation, a principle leveraged in pyrotechnics and industrial flame applications. Understanding these forces allows precise control over

/PeriodicTableCharge-WBG-56a12db23df78cf772682c37.png)

Related Post

Behind the Legend: The Parents Who Shaped Vin Diesel

Reddit Ps5: The Ultimate Guide to News, Rumors, and Community Insights

Valle De Xico FC Vs. Club Marina: Deep Dive Match Preview and Tactical Analysis

10 Unexpected Truths Behind Lexxxiii727S: A Digital Enigma Between Genius and Controversy