Open vs Closed: How Nature’s Circulatory Systems Shape Life on Earth

Open vs Closed: How Nature’s Circulatory Systems Shape Life on Earth

From the radical efficiency of jungle-dwelling arachnids to the precision-driven réseaux of human biology, the circulatory system remains one of life’s most vital circulatory networks—yet not all are built the same. The fundamental distinction lies between open and closed circulatory systems, where fluid dynamics dictate how oxygen, nutrients, and waste traverse the body. While open systems, seen in arachnids and most invertebrates, rely on a simple, diffuse flow, closed systems—characteristic of vertebrates and some invertebrates—ensure tightly controlled, directional transport.

This article explores the shared principles, striking differences, and evolutionary advantages of both systems, revealing how each has enabled survival across millennia.

At the core, the circulatory system serves as life’s highway—a network that dispatching essential substances while removing cellular waste. In closed systems, blood—or its functional equivalent—flows unimpeded through vessels, enabling rapid, targeted delivery.

In contrast, open systems depend on a pseudocoelom or body cavity where hemolymph moves freely through open spaces, contacting tissues directly. This foundational contrast shapes everything from metabolic efficiency to evolutionary adaptability. As biochemist Dr.

Elena Marquez notes, “The shift from open to closed circulation marked a biological threshold—one that unlocked complexity in larger, more active organisms.”

The Open System: Simplicity at the Cost of Efficiency

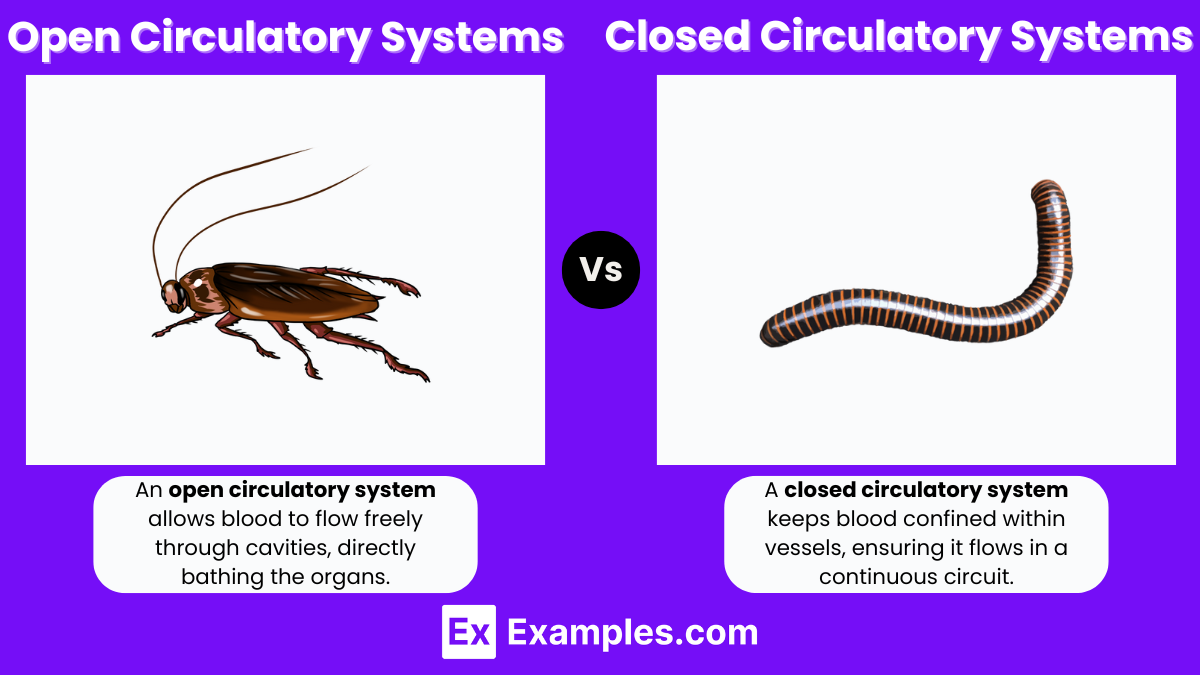

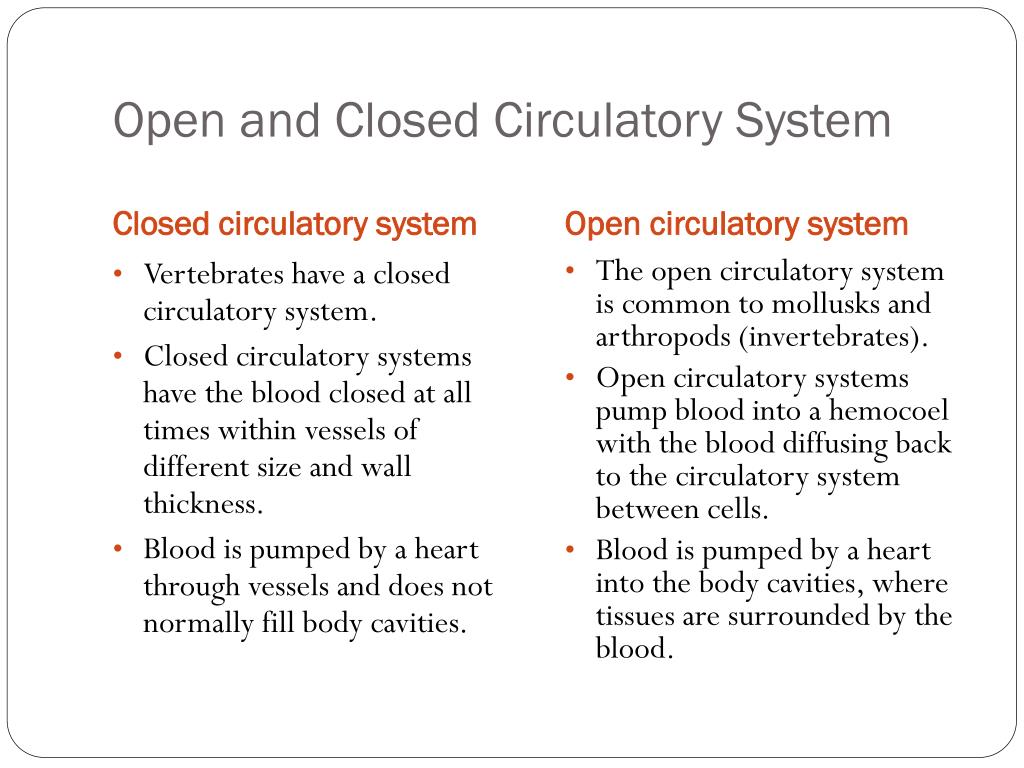

Open circulatory systems are defined by their design: fluid—typically hemolymph—bathes tissues directly within an external body cavity known as a hemocoel. This system dominates in arachnids, insects, crustaceans, and certain mollusks, where budget constraints and evolutionary pathways favored simplicity over complexity.In these organisms, the heart pumps hemolymph into a main vessel called the aorta, which releases fluid into surrounding body compartments through small openings called ostia.

Unlike blood vessels, these passageways lack completeness, allowing hemolymph to flood tissues before returning via passive or minimal muscular pumping. While cost-effective—requiring less energy and fewer specialized components—open systems impose key limitations. Nutrient and oxygen delivery lacks precision; diffusion becomes the primary exchange mechanism, restricting organism size and activity levels.

Insects, for example, thrive in adaptable environments but struggle with sustained high-energy demands below a certain threshold. Take the honeybee, a master of open systems. With a heart compelling hemolymph through its short aortic bulb, it efficiently delivers nutrients to flight muscles—though not at the levels seen in closed systems. Its hemolymph also bathes immune cells directly, supporting defense, albeit less dynamically than the rapid vascular response in vertebrates. Similarly, crabs and spiders use hemolymph not only for transport but also for thermoregulation and calcium transport—critical in their life cycles. Yet energy allocation remains constrained, as inefficient circulation limits rapid adaptation and growth.Open Circulatory System in Action: Ground Robustness Over Speed

The Closed System: Precision Engineered for Complexity

Closed circulatory systems, in contrast, isolate fluid within a continuous network of blood vessels—arteries, veins, and capillaries—ensuring unidirectional, high-velocity delivery.

Primarily found in vertebrates and some cephalopods, this design enables unparalleled control over internal environments, fueling the rise of large, metabolically active bodies.

In mammals, including humans, the heart acts as a powerful pump driving blood through a vast arterial web. Capillaries, with their ultra-thin walls, facilitate rapid exchange—oxygen diffuses into tissues, while carbon dioxide diffuses outward.

This fine-tuned system supports sustained aerobic activity, complex organ development, and thermal regulation. Cephalopods like octopuses exhibit a more advanced closed system with multiple hearts, showcasing evolutionary innovation. Their ability to regulate blood flow to muscles mid-action enables the explosive swimming needed for hunting.

“Closed systems aren’t just about flow—they’re about control,” explains Dr. Rajiv Nair, marine physiologist at the University of Cambridge. “Precision here enables complexity: brains, muscles, organs—all thrive under this regulated supply.”

Structural and Functional Advantages of Closed Systems

Efficiency and Precision - Vessels maintain consistent pressure, minimizing energy loss.- Valves and muscular walls prevent backflow, ensuring forward progress. - Targeted delivery via arterioles and capillaries optimizes cellular supply. - Rapid removal of metabolic waste supports high metabolic rates.

Support for Elevated Activity and Size - Sustains continuous energy supply for large, warm-blooded bodies. - Enables advanced thermoregulation through blood flow modulation. - Facilitates complex organ systems with specialized perfusion needs.

Comparison: Beyond Structure to Biological Impact

The divergence between open and closed systems extends beyond anatomy—it shapes ecological success,

Related Post

The Walking Dead Maggie Rhee and Leah Shaw fight to the death during midseason finale of AMC series

Japan 2023: An Unforgettable Year of Rediscovery and Innovation