Negara-Negara Kepulauan Karibia: A Linguistic Tapestry of 27 Nations Across the Tropical Seas

Negara-Negara Kepulauan Karibia: A Linguistic Tapestry of 27 Nations Across the Tropical Seas

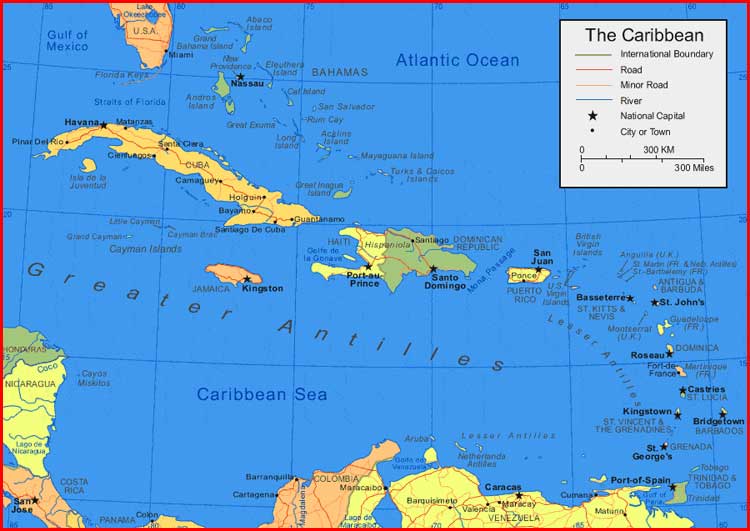

Spread across the azure waters of the Caribbean, the archipelago of Negara-Negara Kepulauan Karibia is far more than a cluster of islands—it is a vibrant mosaic of 27 distinct sovereign states, each shaped by unique histories, cultures, and linguistic heritages. From the large and influential nations like Cuba and Haiti to the smaller, often overlooked atolls and island territories, these countries form a rich linguistic and cultural constellation. Each island nation speaks its own language or dialects, reflecting centuries of colonial legacies, indigenous presence, and post-independence identity formation.

This article serves as a comprehensive guide to understanding the complex, dynamic linguistic landscape of these Caribbean nations—a guide built on deep research and factual clarity to illuminate how language defines community, policy, and connection across the Kepulauan. The Caribbean’s national diversity is staggering, encompassing not only dozens of nation-states but also a spectrum of official languages and dialects shaped by complex historical currents. The region’s languages are not merely tools of communication but markers of identity, sovereignty, and cultural resilience.

Over time, colonial rule introduced European languages—Spanish, English, French, Dutch—as dominant administrative and educational mediums, often suppressing or marginalizing local tongues. Yet, indigenous languages such as Kalinago, Garifuna, and variations of Arawakan persist, often revitalized through grassroots movements and cultural initiatives.

Linguistic Foundations: Colonial Legacies and Post-Independence Realities

The linguistic map of Negara-Negara Kepulauan Karibia bears the imprint of centuries of empire.Spanish and English remain dominant due to prolonged colonial governance, with Cuba (Spanish), Jamaica and Trinidad & Tobago (English), Haiti (French), and Guyana (English) each retaining colonial tongues as official languages. French plurality manifests in Haiti and Martinique, while the Netherlands influences Dutch-speaking populations in Curaçao and Aruba. Yet post-independence, many nations embraced multilingual policies to reflect their multifactorial realities.

In Haiti, Haitian Creole and French coexist as official languages, a deliberate affirmation of cultural pride after decades under French rule. Similarly, in Trinidad & Tobago, English remains the lingua franca of government and business, but creole speech—“Caribbean English Creole”—is deeply embedded in daily life and cultural expression. Even smaller island states often assert linguistic identity: the Dutch-based Papiamentu thrives in Aruba and Bonaire, a creole forged from African, Dutch, and Spanish influences.

These choices reflect a broader trend: language in the Caribbean is not static—it evolves through resistance, revival, and reinvention.

Understanding this linguistic layering requires recognizing the administrative and social roles each language plays. Official languages ensure continuity in governance, law, and education, while indigenous and creole varieties anchor local identity and intergenerational memory.

The tension and cooperation between these linguistic pillars form the backbone of national cultural policy across the archipelago.

Language Policy and Educational Frameworks Across the Kepulauan

Across Negara-Negara Kepulauan Karibia, language policies vary significantly, reflecting each nation’s priorities in education, national unity, and cultural preservation. In Haiti, the government’s commitment to Haitian Creole as the primary vehicle for primary education is groundbreaking—since the 1980s, reforms have steadily elevated the creole’s status, challenging long-standing hierarchies that prioritized French. This shift aims not only at accessibility but also at reclaiming linguistic dignity for Haiti’s majority.In contrast, Jamaica’s educational system maintains English as the medium of instruction, though regional dialects such as Patwa are increasingly acknowledged in cultural studies and creative expression. Meanwhile, in Aruba and Curaçao, Dutch remains central, though both territories offer instruction in Papiamentu and Spanish, depending on regional needs. Trinidad and Tobago exemplify multilingual pragmatism: English serves as the official language, but creole speech dominates informal and artistic domains, with structured efforts to document and standardize regional dialects.

In smaller states like St. Kitts and Nevis or Dominica, efforts to preserve indigenous expressions—through oral history projects and school curricula—have gained traction, supported by regional bodies like CARICOM’s Language and Heritage Initiative. These policies highlight a critical tension: balancing global integration (via English and French as international business languages) with local authenticity (through creole and indigenous languages).

Countries leading in linguistic inclusivity often report stronger social cohesion and cultural vitality.

Key indicators of language policy success include standardized teaching materials, public media availability in native languages, and government-sponsored literacy campaigns. For instance, Haiti’s recent push to publish textbooks in Haitian Creole and French has boosted educational outcomes, especially in rural areas where English or French comprehension remains limited.

Indigenous and Minority Languages: Voices of Resistance and Survival

Beneath the dominant colonial tongues lie voices of enduring indigenous heritage.The Kalinago people of St. Kitts and Nevis preserve a language once nearly lost, now kept alive through cultural programs and community initiatives. The Garifuna, dispersed across Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and parts of the Dutch Caribbean, maintain a distinct Arawakan language, recognized internationally for its cultural significance.

Arawakan dialects, though often overshadowed, form vital links to pre-colonial Caribbean life. Kalinago, spoken on a narrow strip of land in St. Kitts, stands as a resilient testament to indigenous persistence.

Once endangered, it has seen revitalization through immersion schools and digital archives. According to Dr. Michael Jones, a Caribbean linguist, “These minority languages are not relics—they are living systems of identity and knowledge, holding ecological wisdom and oral traditions vital to understanding the nation’s true heritage.” In Sint Maarten, the critically endangered Sranan Tongo (a creole with West African roots) persists in informal settings, supported by cultural NGOs advocating for recognition.

Digital tools now play a growing role: mobile apps, online dictionaries, and audio recordings are helping document and teach these languages, ensuring younger generations connect with ancestral speech even in urbanized environments.

The survival of such languages depends on community ownership, institutional support, and innovative documentation—efforts that transcend mere preservation to empower marginalized voices in national discourse.

Language, Culture, and Identity in the Caribbean’s Public Sphere

Public life in Negara-Negara Kepulauan Karibia is a vibrant arena where language both unites and distinguishes. National anthems, parliamentary debates, media broadcasts, and educational systems all reflect linguistic choices that shape collective identity.In Jamaica, the global influence of reggae and dancehall music—steeped in Jamaican Patois—projects a powerful cultural identity worldwide, even as English remains the administrative language. Television and radio stations increasingly feature programs in local creoles and indigenous languages, offering representation to communities historically excluded from mainstream media. In Haiti, radio broadcasts in Haitian Creole during crises have proven crucial for rapid, accessible communication—demonstrating how language functions not just symbolically, but practically in times of need.

Urban centers like Kingston, Port-au-Prince, and Willemstad host dynamic linguistic ecosystems where multilingualism is the norm. Street signs, shopfronts, and social media blend English, French, Spanish, and creole, reflecting the fluid, adaptive nature of Caribbean communication. This creative hybridity is not chaos—it is a structured, lived reality that enriches national culture and enhances social belonging.

The influence of language extends beyond daily life into national storytelling. Literature, music, and oral history preserve histories through linguistic expression, affirming that to speak a Caribbean nation’s language is to honor its soul.

Challenges and Opportunities in Preserving Language Diversity

Despite progress, endangered languages in the Kepulauan face persistent threats. Urbanization draws youth away from traditional speech communities, while globalization pressures prioritization of widely spoken languages.UNESCO estimates over 40% of Caribbean languages are at risk of extinction within decades—a crisis deepened by limited funding for linguistic research and education. Yet, opportunities abound. Regional cooperation through CARICOM and partnerships with international organizations like UNESCO and SIL International are pioneering language documentation and revitalization programs.

Digital platforms now offer unprecedented tools: AI-powered transcription, mobile learning apps, interactive dictionaries, and social media communities foster innovation in language education. Educational reforms anchored

Related Post

This Is Becoming Right Now Emmanuel Esparza How This Is Happening Recently

The Future of Geminitay Twitter: Instant Connections, Instant Impact in Digital Communication

Me Too, Unveiled Through Lyrics: How Song Lyrics Amplified a Global Movement