Monty Python and the Holy Grail: A Hilarious Journey Through Ridiculous Legends

Monty Python and the Holy Grail: A Hilarious Journey Through Ridiculous Legends

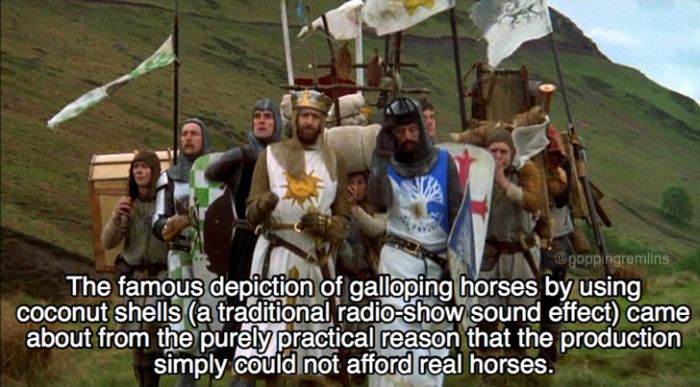

From sword-swinging knights on a quest for a cracker-barrel mythical artifact to absurd dialogue that etched itself into comedy history, Monty Python and the Holy Grail is not merely a film—it is a cultural earthquake wrapped in surreal absurdity. Released in 1975, this landmark of British satire delivers a comedy adventure where logic dissolves faster than King Arthur’s armor on a wet morning, replaced instead by riddles, nonsense, and slapstick that still provoke giggles nearly five decades later. What began as a low-budget fantasy parody evolved into a defining work of anarchic humor, shaping generations of comedians and redefining the boundaries of cinematic absurdity.

The film opens with a critical moment: Arthur (Graham Chapman) assembling his knights—each embodying over-the-top tropes from chivalric clichés to outright comedy stock characters like the preferential Frenchman (Éric Idle) and the chatty Frenchman (John Cleese). Their quest: find the Holy Grail, a personification of divine grace wielded humorously as a mysterious, often frustrating prize. As Sir Bede疾, “Order, beware!

The First Knight is *empty*!”—a rallying cry delivered with just enough earnestness to mock the gravitas of the entire genre. These early scenes establish the film’s unique tone: reverence thrown to the ground beneath a log it turns into. Central to the enduring appeal is the film’s clever subversion of Arthurian legend tropes.

Medieval romance conventions—quests, trials, chivalric codes—are weaponized with double entendres and barrel humor. Consider Sir Lanced’s bellow: “Give antlers to the stag!”—a purported solution to a confusing dilemma that underscores how far the story dipped into surreal wordplay.inees at every twist are not just punchlines but clever commentary on how blind faith and ritualistic behavior often overshadow reason.

The Triumph of Absurdity: Key Moments That Made History

The film’s brilliance lies in its ability to balance machinery of comedy with narrative momentum.One of its most iconic scenes is the infamous “Handle with Care” sequence, in which King Arthur, bless his chivalrous heart, fumbles with a pilgrim’s staff, accidentally setting the journey’s tone—good-natured chaos rather than grim destiny. “She’s *a go-between*, and a *very handy one*!” proclaims the now-forgotten Merlin, blending whimsy with functional storytelling. Each scene stomps the ground beneath epic cliché, proving that even sacred quests are ripe for mockery.

Another standout is the Holy Grail itself—a surprisingly mundane cauldron, humorously understated despite being the film’s central prize. “It’s not *entirely* unreliable,” quipped Robinson, the monk, with broader implications about faith’s dependence on context—a subtle dig disguised as nonsense. The dialogue hums with layered satire: knights debating the Grail’s value, monks in ambiguous proceedings, and a nun offering the only sincere moment amid the banter, “I seek grace, not just glass.” The film also introduces memorable villains whose roles transcend laughter.

Lady Complete (Connie Booth and Terry Jones) marries romantic misogyny with whimsical exposition, warning, “The Grail’s *abhors* perfectionists!”—a line that skewers both medieval romanticism and modern perfectionism with equal bite. Meanwhile, King Ralph’s excruciatingly poor leadership—“Why wouldn’t I just *ask*?!”—epitomizes bureaucratic absurdity wrapped in slapstick, reinforcing how far farce has come from naturalism.

Behind the Laughter: The Creativity of Monty Python’s Masterstroke

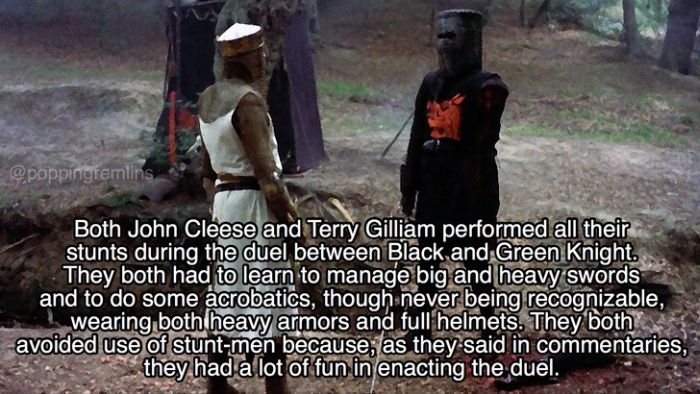

What elevated Monty Python and the Holy Grail from sketch comedy to cinematic legend was its inventive blend of biting satire, physical humor, and genre parody—executed with surgical precision by the ensemble.Python’s writers-turned-actors exploited traditional adventure film tropes not just for laughs, but to dismantle them. The film includes a furious joust, nearly as epic as the quest itself, where armor clatters like a cheap metal orchestra, and sword clashes ring hollow against the absurdity of the mission. Such scenes aren’t random; they’re carefully crafted assaults on audience expectations.

The script draws heavily from medieval romance literature—Sir Thomas Malory’s *Le Morte d’Arthur* becomes a playground of irreverence. With no strict adherence to plot or narrative cohesion, the film instead chooses thematic consistency in rebellion. As Graham Chapman observed, “We weren’t making a movie—we were making *anarchy*, and the audience loved it.” This ethos resonated globally, embedding the film into comedy DNA where “Howard’s End” and “Borat” emerge as distant echoes of this revolutionary approach.

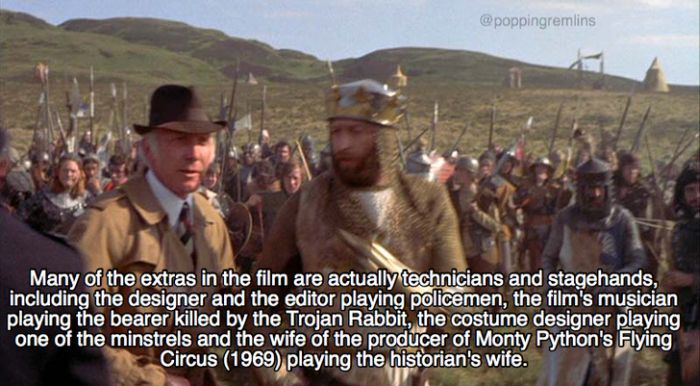

Equally significant is the casting. Equipping the group with actors who embodied hyper-specific archetypes—Idle’s neurotic French knight, Jones’ sly barscribe—created immediate comedic recognition. Their chemistry thrives on escalating absurdity: Hercules, in an avalanche of comedic timing, insists the Grail must be “*the chal

Related Post

Baddiehub.com: Where Bold Aesthetics Blend with Cultural Identity in Middle Eastern Fashion

Gadsden Mugshots, Alabama: What Are They Hiding Behind The Frames In This Town’s Shadows?

Top Rainmeter Skins for Windows 10: Transform Your Desktop with Stylish Functionality

Unraveling the Mystery: Is Jung Kook Gay?