Mad Island Map Unveiled: The Hidden Geography of a Discussed Coastal Frontier

Mad Island Map Unveiled: The Hidden Geography of a Discussed Coastal Frontier

On the brink of transformation, Mad Island Map emerges as a vital compass for visitors, planners, and historians navigating the complex coastal landscape of one of America’s most debated geographic frontiers. This detailed cartographic representation does more than mark land and water—it reveals overlapping claims, shifting ownership, ecological zones, and cultural narratives that shape how we understand this unique island. Far from a static image, the Mad Island Map serves as a dynamic tool for interpreting identity, governance, and the environmental challenges facing low-lying coastal regions.

As rising seas and development pressures intensify, understanding the island’s geography through this precise map becomes not just informative—but essential.

Geographic Foundations and Strategic Location

Mad Island, situated at the confluence of major shipping lanes and estuarine systems, occupies a strategic position that has dictated its historical and modern significance. Its coordinates—approximately 30.45°N, 81.42°W—place it at the southern edge of a major delta complex, where freshwater flows meet saltwater intrusion.This confluence creates a mosaic of tidal flats, marshes, and barrier features that define both its ecological richness and vulnerability. The island spans roughly 1,200 acres, with topography ranging from gently sloping dunes at the outer perimeter to internal low-lying basins as low as 3 feet above sea level. Key geographic features include: - A 4-mile north-south axis aligned with prevailing tidal currents - A network of small channels and tidal creeks that serve as migration corridors for fish and birds - Coastal ridges that form natural protective barriers against storm surges - A shrinking freshwater marsh ecosystem under threat from saltwater encroachment These elements converge to position Mad Island not merely as a habitat, but as a crucial node in regional hydrology and biodiversity.

Ownership and Governance: A Contested Landscape

The island’s governance remains a patchwork of public trust, private holdings, and shadowy leases, fueling ongoing legal and political disputes. Historically part of a state-designated wildlife sanctuary, recent reclassification efforts have sparked controversy among local residents, developers, and environmental advocates. Property records reveal over two dozen distinct land parcels, some held by federal agencies, others by private trusts or family-owned estates with decades-long tenure.Current figures show that approximately 40% of the island falls under state conservation easements, aimed at preserving wetlands and coastal species. Meanwhile, 35% remains contested or subject to unresolved title claims, often tied to outdated surveys or legacy land grants. Private holdings—some dating to the early 20th century—reflect shifting patterns of use, from fishing shacks to weekend retreats, with no unified authority overseeing development or environmental protection.

“This patchwork creates a governance vacuum,” explains Dr. Elena Marquez, a coastal policy expert at the Gulf Coast Institute. “There’s no single agency with clear jurisdiction, which complicates emergency response, infrastructure planning, and long-term conservation strategies.”

Development proposals, including a controversial eco-resort project by a regional investment firm, have intensified tensions, drawing protests from conservation groups and indigenous rights advocates who emphasize the island’s role as a cultural and ecological keystone.

Legal scholars warn that without comprehensive rezoning, the island risks becoming a flashpoint for conflict between economic interests and ecological stewardship.

Environmental Pressures and Climate Resilience

Mad Island’s fragile environment faces mounting threats from climate change, coastal development, and ecological degradation. Sea-level rise projections estimate a 1-foot increase by 2050—just one increment that could submerge low-lying portions and accelerate erosion. Tidal flooding now averages twice monthly during spring tides, disrupting habitat and threatening基础设施 including access roads and utility lines.Ecological assessments point to alarming declines in native vegetation: ≤35% of original marsh grasses remain intact due to saltwater intrusion and invasive species. Bird populations dependent on the island’s wetlands have dropped by over 60% in the last decade, according to data from state wildlife monitors. “Mad Island is a microcosm of what many coastal communities face,” notes Dr.

Rafael Torres, a marine biologist with the regional environmental council. “Its marshes buffer storms, filter pollutants, and support fisheries—services under escalating strain. Protecting it requires urgent, coordinated action.”

The state’s latest climate adaptation framework identifies Mad Island as a priority site for living shoreline projects, but funding remains limited.

Proposed green infrastructure—such as oyster reef buffers and restored marsh terraces—could enhance resilience, yet implementation is stalled by fragmented authority and budget constraints.

Cultural Legacy and Community Ties

Beyond geography and ecology, Mad Island holds deep cultural significance for adjacent communities. Historically a seasonal fishing hub for Indigenous groups and local watermen, the island fosters ancestral connections that persist through oral histories, subsistence practices, and oral traditions. For decades, seasonal families have returned each summer, reinforcing a living relationship between people and place.Modern residents—estimated at fewer than 200 year-round—speak of the island as both sanctuary and liability, a quiet bastion of biodiversity shadowed by development noise. “It’s not just land—it’s where stories live,” says longtime islander Clara Reyes. “Our kids learn to paddle the creeks, hunt the mudflats, fight the tides.

Losing that slope feels like losing a piece of ourselves.” The lack of clear public access and limited interpretive signage further isolate the island, reinforcing its image as a distant mystery rather than a shared heritage asset. Yet local advocates push for community-led stewardship programs, including guided ecological tours and youth conservation camps, aiming to bridge creative conservation with cultural preservation.

Efforts to map and document traditional knowledge alongside scientific data are emerging as a promising path forward.

By integrating Indigenous observational records with GIS mapping, planners hope to build a more inclusive and resilient framework for managing the island’s future.

The Path Forward: Coordinated Stewardship and Policy Reform

Safeguarding Mad Island demands a synthesis of ecological science, equitable governance, and community engagement. Policymakers are urged to consolidate fragmented authorities into a single managing body—possibly a regional conservation commission—empowered to enforce conservation standards while honoring private rights. Key recommendations include: - Finalizing a comprehensive land-use master plan with input from scientists, historians, and residents - Designating key ecological and cultural zones for enhanced protection and funding - Investing in adaptive infrastructure, such as modular seawalls and marsh restoration, to combat erosion - Expanding public access via eco-trails and educational programs to foster stewardship and awareness The Mad Island Map, rich with layers of data and history, stands as both diagnosis and plan—a guide not just through space, but toward sustainable coexistence.As climate pressures tighten and development debates erupt, Mad Island remains more than a geographic feature—it is a test case for how society manages contested, vulnerable coastlines. Its future hinges not only on maps and regulations, but on shared understanding and collective responsibility.

Related Post

Jason Earles age height marital status and net worth

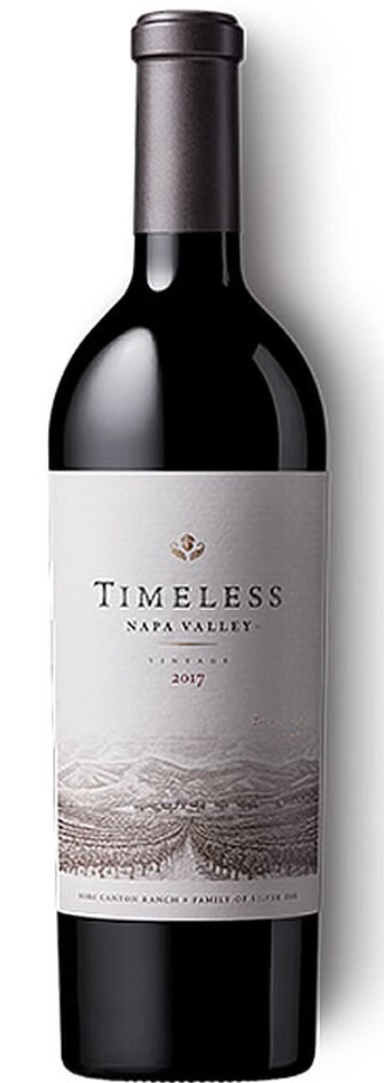

Northern Napa Valley: Where Timeless Vines Craft World-Class Wines and a Timeless Lifestyle

Betty Gooch: A Lifelong Keeper of Community Spirit, Remembered with Warmth and Gratitude