Landscape Analysis in AP Human Geography: Decoding the Shaped World Around Us

Landscape Analysis in AP Human Geography: Decoding the Shaped World Around Us

Landscape Analysis in AP Human Geography offers a powerful lens through which to interpret the intricate relationship between human societies and the physical and built environments they inhabit. Far more than a surface-level description of terrain, climate, or cities, this analytical framework dissects the layers of cultural, economic, and historical influences embedded in landscapes—transforming observable patterns into meaningful narratives about human choice, power, and adaptation.

At its core, landscape analysis integrates spatial patterns with human behavior, identifying how people modify, perceive, and value their surroundings.

Richard Hartshorne’s foundational spatial model—developing concentric circles from urban cores outward—remains relevant, illustrating population density gradients and functional zoning that reveal underlying socio-economic dynamics.

For example, distinguishing between high-density commercial districts, sprawling residential suburbs, and fragmented rural farmland reflects not just geography but decades of policy, migration, and industrial shifts. The Three Pillars of Landscape Analysis

Landscape analysis hinges on three interconnected dimensions: environmental, cultural, and economic. Each shapes and responds to the others in a dynamic feedback loop. Environmental Influences

The physical landscape—mountains, rivers, soil fertility, and climate—acts as both constraint and opportunity.

In the Nile Basin, annual flooding historically dictated agricultural cycles, leading to the rise of centralized Egyptian civilization.

Reliance on predictable water flows enabled surplus food production, which in turn supported urban development, literacy, and bureaucracy. Conversely, arid regions like the Sahara fostered nomadic pastoralism, where mobility replaced sedentary farming as a survival strategy. Environmental limits often determine settlement patterns; steep slopes discourage large construction, while fertile valleys attract dense populations.

Cultural Imprints

Human culture leaves indelible marks on landscapes, turning natural settings into symbolic or functional spaces. Religious, colonial, and national narratives embed themselves into the built environment. Colonial cities across Latin America, such as Lima and Mexico City, exemplify imposed grids superimposed on indigenous settlements—visible in plazas, cathedral placements, and street alignments that reflect both conquest and cultural erasure.Religious landscapes, too, reveal deep-seated values: the Ramayana-inspired temple architecture of South India contrasts with the minimalist Islamic symmetry of Mughal mausoleums, each shaping social behavior and collective identity.

Economic Shaping Forces

Economic systems drive spatial organization, from ancient trade routes to modern megacities. The Silk Road’s network transformed arid Central Asian steppes into commercial corridors, where oasis towns evolved into cultural melting pots. Today, globalized industrial zones and special economic zones—such as China’s Shenzhen—demonstrate how capitalism reshapes landscapes overnight, replacing rural villages with logistics hubs and tech parks within decades.These shifts reflect not just capital flows but also labor migration and environmental trade-offs, like pollution and land degradation.

Case Studies in Landscape Transformation

Multiple landscapes illustrate how human activity redefines geography. In the American Midwest, vast oceans of corn and soybean fields—monocultures enabled by mechanization and subsidies—replace native prairies, altering biodiversity and water cycles.This transformation underscores the tension between agricultural productivity and ecological sustainability.

Urban expansion offers another lens: cities like Lagos, Nigeria, grow at breakneck speed, with informal settlements sprawling across wetlands and floodplains, exposing vulnerability to climate risks and governance gaps. Such landscapes reveal not static environments but contested, evolving spaces shaped by inequality, policy, and human ambition.

Mountain, River, and Margin: Geographical Boundaries and Identities

Mountain ranges and rivers often function as natural borders, but their social significance is actively constructed.The Andes form a formidable physical divide in South America, yet indigenous groups like the Quechua have navigated and redefined these barriers through trade, pilgrimage, and shared language reforms. Similarly, the Rio Grande separates the United States and Mexico, but border towns like El Paso–Ciudad Juárez blend cultures through cross-daily migration, transforming a symbolic line into a lived zone of exchange and tension.

Methodologies and Tools of Modern Landscape Analysis

Contemporary geographers employ diverse tools to interpret landscapes.Geographic Information Systems (GIS) enable the overlaying of demographic, economic, and environmental data, revealing spatial correlations invisible to the naked eye. Remote sensing through satellites tracks deforestation, urban sprawl, and coastal erosion in real time, supporting evidence-based policy. Yet, qualitative methods—ethnographic fieldwork, historical cartography, and oral histories—ground analysis in lived experience, ensuring that numbers reflect human stories, not just statistics.

The Role of Power in Shaping Landscapes

Power structures profoundly influence landscape formation. Colonial legacies persist in the form of segregated neighborhoods, land tenure systems, and resource extraction zones designed to serve external interests. Post-colonial governments often repurpose colonial infrastructure—renaming streets, redeveloping governor’s palaces into museums—to reclaim identity and legitimacy.Even today, decisions about infrastructure, conservation, and urban renewal reflect political priorities, sometimes marginalizing vulnerable populations. Landscape analysis thus becomes a critical tool for exposing inequities and advocating for inclusive development.

Environmental Justice and Landscape Conflict

Landscapes shaped by human intervention increasingly reflect divergent access to resources and environmental risks.Industrial zones and landfills are disproportionately located near low-income communities, exposing residents to pollution and health hazards—a phenomenon central to environmental justice discourse. Conversely, protected areas such as national parks often displace indigenous peoples, raising ethical questions about conservation versus cultural rights. These conflicts underscore the moral dimension of landscape analysis, urging Geographic practitioners—and society at large—to engage with justice in spatial design.

Learning from Past and Shaping Future Landscapes

Landscape analysis is not merely descriptive; it is indispensable for planning resilient futures. Historical patterns illuminate long-term trends—how cities grow, how agriculture expands, how borders harden—while current changes highlight urgent challenges like climate migration and urbanization pressures. By decoding these layers, geographers inform policymakers about sustainable land use, disaster preparedness, and equitable development.The physical land beneath our feet is not passive. It bears the imprints of human decisions, desires, and struggles. What we choose to preserve, transform, or protect defines not only our environment but also the societies we aspire to become.

Through rigorous, empathetic landscape analysis, AP Human Geography empowers us to read our world critically—and act wisely. So next time you pass a highway stretching to the horizon or a city skyline rising through clouds, pause: you’re not just seeing scenery—you’re witnessing human history, culture, and power etched into the very fabric of the Earth.

Related Post

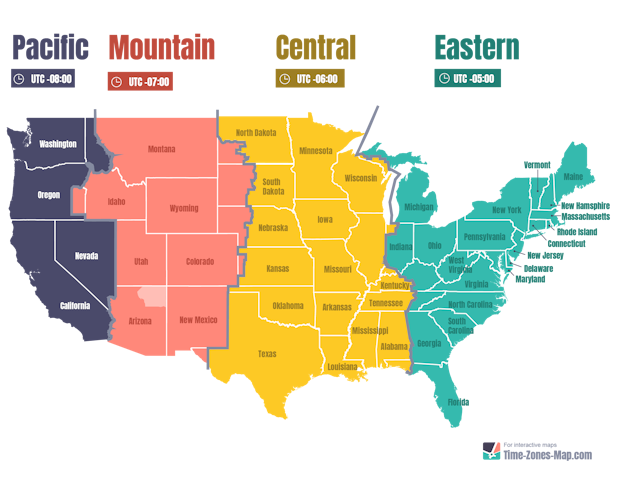

Utah’s Current Time: Where Mountain Clocks Side With Mountain Time Standard

Navigating Portugal Jobs: Lucrative Opportunities For US Citizens in 2024

Scrutinizing the Subtleties of Patimat: A Exhaustive Overview

Log Me In 123: Your One-Stop Portal to Unfitileless Digital Identity Management