Keratinized vs Non-Keratinized Stratified Squamous Epithelium: The Critical Differences Shaping Human Organ Function

Keratinized vs Non-Keratinized Stratified Squamous Epithelium: The Critical Differences Shaping Human Organ Function

Nestled within the protective layers of the human body, stratified squamous epithelium stands as a vital barrier, adapting uniquely across tissues through keratinization—a biochemical transformation that fundamentally determines its durability and function. While both keratinized and non-keratinized forms belong to the same epithelial classification, their structural distinctions dictate vastly different roles in protection, moisture retention, and physiological response. Understanding whether an epithelium is keratinized or not is more than a superficial histological detail—it’s a window into the body’s defense strategy and specialization across skin, oral cavity, esophagus, and other mucosal surfaces.

Structural Foundations and Functional Divide: Stratified squamous epithelium consists of multiple rows of cells stacked vertically, with each layer contributing to barrier strength. The key difference lies in the presence or absence of keratin—a tough, insoluble protein that fills the upper layers. Keratinized epithelium, found in the skin’s epidermis and the deeper layers of mucosal linings, develops a thick, protective outer layer via terminal differentiation.

In contrast, non-keratinized epithelium retains nuclei in its surface cells and relies on a moist, gel-like surface, maintaining hydration and flexibility. This structural divergence directly influences permeability, susceptibility to damage, and cellular turnover.

Keratinized Stratified Squamous Epithelium: A Shield Against Harsh Environments

Keratinization is a progressive process beginning at the basal layer, where cells are metabolically active and uniform. As they migrate upward, cells undergo terminal differentiation: nuclei disintegrate, cytoplasm fills with keratin filaments, and the cell membranes harden into a protective cap.This transformation results in a dense, impermeable barrier ideal for fighting abrasion, dryness, and environmental aggressors.

Key Features: - Surface cells are flattened, dead, and packed with keratin—measuring up to 20–30 layers thick. - Resists mechanical stress, fungal invasion, and water loss.

- Exhibits low permeability, preserving tissue hydration at the cellular level. - Predominantly resides in the epidermis and subepithelial zones of oral, esophageal, and genital mucosa. - Clinically significant in conditions like psoriasis, where accelerated keratinization thickens and distorts tissue architecture.

Functional Advantages and Limitations: The keratinized phenotype excels in high-wear environments—think of calloused hands or the esophagus during swallowing—by minimizing friction and degradation.

However, this durability sacrifices elasticity and moisture retention, making it less suitable for dynamic interfaces needing constant hydration, such as the inner mouth or vaginal mucosa. “Keratinization is nature’s compromise between protection and flexibility,” notes Dr. Elena Torres, histopathologist at the Mayo Clinic.

“While it shields against trauma, it limits regeneration speed and sensory feedback in mucosal linings.”

Non-Keratinized Stratified Squamous Epithelium: Preserving Moisture and Flexibility

Unlike its keratinized counterpart, non-keratinized epithelium maintains nuclei in the superficial layers and relies on a moist extracellular matrix. This structure preserves cellular hydration and elasticity, essential for organs requiring constant mechanical adaptability and barrier moisture.Key Features: - No keratin deposition; cells retain living cytoplasm with active hydration.

- Surface is smooth and pliable, enabling dynamic tissue movement. - Thin barrier with high permeability to water, ions, and immune mediators. - Found lining the mouth, esophagus, vagina, and parts of the respiratory tract.

- Rapid turnover supports quick repair of surface micro-abrasions.

Biological Significance in Dynamic Environments: Non-keratinized epithelium thrives in zones subject to constant mechanical stress and environmental fluctuations—such as chewing, swallowing, and sexual interaction—where maintaining moisture and elasticity prevents tearing and infection. “This epithelium functions like a living sponge,” explains Dr. Marcus Lin, schema biologist at Harvard Medical School.

“Its fluid-filled structure and sponge-like texture allow continuous room-temperature communication with underlying tissues while guarding against pathogens.” Notably, this form supports rapid immune surveillance and cellular regeneration, underpinning mucosal immunity.

Clinical and Evolutionary Implications

The divergence between keratinized and non-keratinized epithelia reflects millions of years of adaptation. Evolution has fine-tuned each type to match tissue function: robust keratinization protects exposed, high-traffic surfaces, while non-keratinization supports sensitive, moist linings that must balance protection with mobility. Médical responses to injuries or infections often target these structural traits—topical therapies enhancing keratin renewal aid skin repair, while hydration strategies preserve non-keratinized mucosal health.Clinical conditions often reveal the functional stakes: - Keratinization defects can lead to conditions like ichthyosis, where dry, scaly skin results from failed keratinization. - Loss of non-keratinized tissue integrity increases susceptibility to infections and ulcerations, as seen in xerostomia (dry mouth) or cervical erosions. - Understanding these differences guides tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, where lab-grown epithelia must replicate native keratinization or hydration profiles for optimal integration.

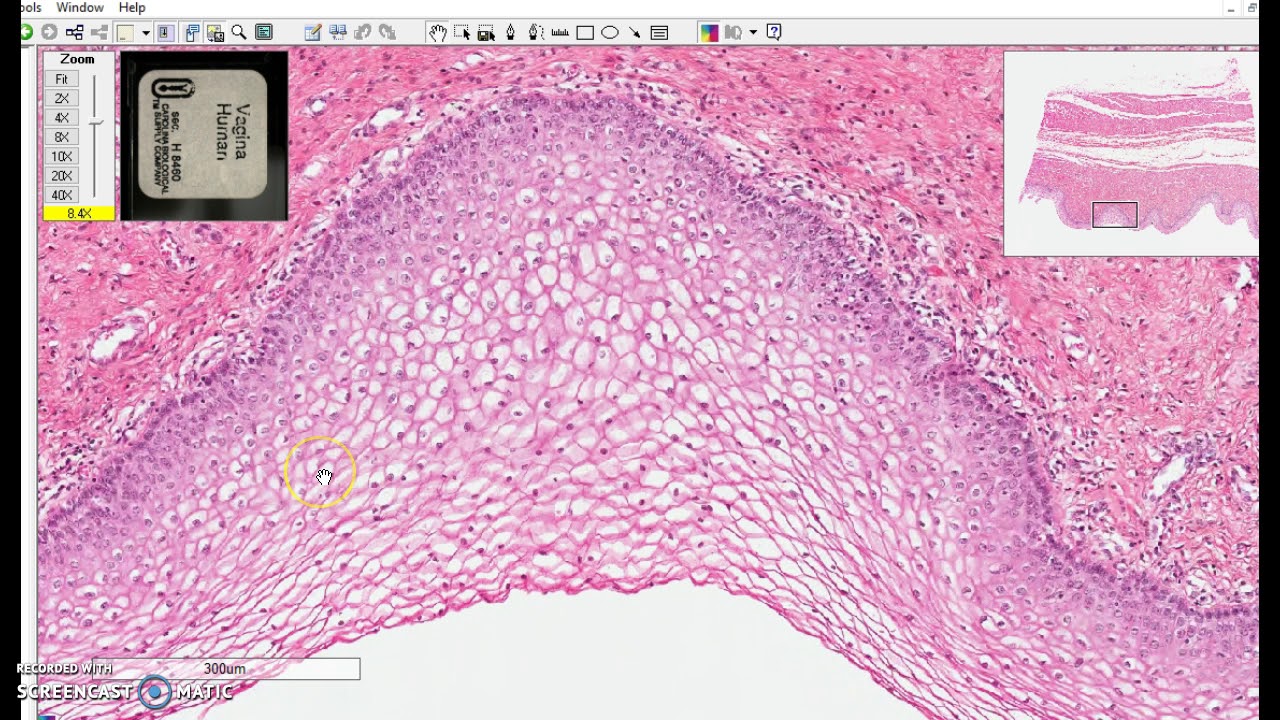

Histological Distinction: Visual Clues in Skin and Mucosal Biopsies

Microscopically, the contrast is striking.In keratinized zones, stains reveal orthogonally oriented keratin filaments, thickened intercellular bridges, and dense corneum layers. In non-keratinized epithelium, stained sections highlight nucleated basal cells in direct contact with basement membrane and a moist, translucent surface. These distinctions are critical for pathologists diagnosing epidermal dysplasia, lichen planus, or HPV-related changes across tissue layers.

Ultimately, stratified squamous epithelium epitomizes biological specialization—keratinized layers fortified for defense and non-keratinized sheets built for function and renewal. Their classification is far from trivial: it reveals how form shapes fate in the body’s defense system, where every cell’s role is calibrated to its environment. From the rugged callus of the palm to the moist lining of the esophagus, this epithelial duality underscores evolution’s precision in equipping the human body to thrive across extremes.

Related Post

David Neymar Jr.: The Rising Star Following in His Father’s Shadow — Everything You Need to Know

Unveiling Hidden Energies: How the Florida Ley Lines Map Shapes Understanding of the Sunshine State’s Subtle Geomantic Currents