Ionization Unlocked: How the Boundless Energy of Charged Particles Powers Science and Industry

Ionization Unlocked: How the Boundless Energy of Charged Particles Powers Science and Industry

Ionization—the transformation of atoms into charged particles—lies at the core of countless technological advances and natural phenomena. Though often invisible, this process underpins key functions in materials science, environmental control, medical imaging, and even night sky glows. By stripping electrons from atoms, ionization creates ions—charged molecules capable of electrical conductivity, chemical reactivity, and interaction with electromagnetic fields.

Understanding ionization is not just an academic pursuit; it’s a gateway to harnessing powerful forces that shape modern life.

At its essence, ionization occurs when an atom or molecule gains or loses electrons, usually through energy input such as heat, light, or electrical discharge. When an atom excedes or surrenders electrons, it becomes a positive or negative ion.

Depending on the energy source, ionization can be thermal (heat-induced), photoionization (light energy), or collision-based (particle impacts). Each mechanism offers distinct pathways and applications. “Ionization is not merely a scientific curiosity—it’s the invisible engine behind radiation detection, air purification, and even energy storage,” notes Dr.

Elena Torres, a physicist specializing in plasma dynamics at the National Institute of Advanced Sciences.

One of the most tangible forms of ionization we experience daily is in air discharge phenomena—think thunderstorms sparking trees, or static electricity zapping fingertips. These events release ionized air molecules, creating conductive paths for electric currents.

In controlled environments, ionization powers devices like ionizers used in air purifiers. These devices emit negative ions that attach to airborne particles, neutralizing them and enabling gravitational settling. Manufacturers such as Alfa Bond and Dyson integrate ionization technology to deliver cleaner indoor air, reducing allergens and pollutants without chemicals.

From Industrial Furnaces to Medical Diagnostics: Diverse Applications of Ionization

Ionization extends far beyond atmospheric effects, driving innovation across multiple industries through precision and control.In materials processing, ionization plays a critical role. Plasma, an ionized gas state formed through high-energy ionization, enables cutting-edge manufacturing techniques such as plasma cutting—a method that slices metals with extreme precision. Also, ion implantation in semiconductor fabrication alters the electrical properties of silicon wafers, allowing the creation of microchips that power smartphones, computers, and advanced sensors.

“Ion implantation is the backbone of modern microelectronics,” explains Dr. Raj Patel, an engineer at FlexEnable, a nanotechnology firm. “By precisely injecting ions like boron or phosphorus, we create the p-n junctions fundamental to electronic function.”

Medical technology relies heavily on ionization for both diagnosis and treatment.

X-ray and gamma-ray imaging depend on ionizing radiation interacting with body tissues to produce contrast, revealing internal structures without invasive procedures. Radiation therapy uses ionizing radiation to target and destroy cancer cells by disrupting their DNA. Cognitive therapies such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) leverage ion currents to influence brain activity, treating conditions like depression.

“Ionizing beams deliver targeted energy with remarkable accuracy,” states Dr. Maya Lin, a biomedical physicist at Johns Hopkins Hospital, “minimizing collateral damage while maximizing therapeutic impact.”

Environmental applications of ionization are gaining momentum as sustainability becomes paramount. Ion generators deployed in wastewater treatment break down organic pollutants and neutralize pathogens, creating safer effluent streams.

In air quality management, ionization reduces volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and fine particulates, addressing urban smog and indoor air contamination. These systems work silently in municipal plants, industrial hubs, and even residential HVAC units—quietly revolutionizing clean air initiatives.

Sources of Ionization: The Energy That Transforms Matter

The process of ionization requires energy input strong enough to overcome electron binding forces.Common sources include:

- Thermal Ionization: Found in high-temperature environments like fusion reactors or incandescent flames, where thermal energy liberates electrons through intense heat.

- Photoionization: Caused by high-energy photons—such as ultraviolet or X-ray radiation—capable of forcing electrons free via the photoelectric effect, central to spectroscopy and solar cell operation.

- Collisional Ionization: Particles accelerated by electric fields or heat collide with atoms, transferring sufficient energy to dislodge electrons, fundamental in plasma physics and fluorescent lighting.

The Science in Action: Key Principles and Mechanisms

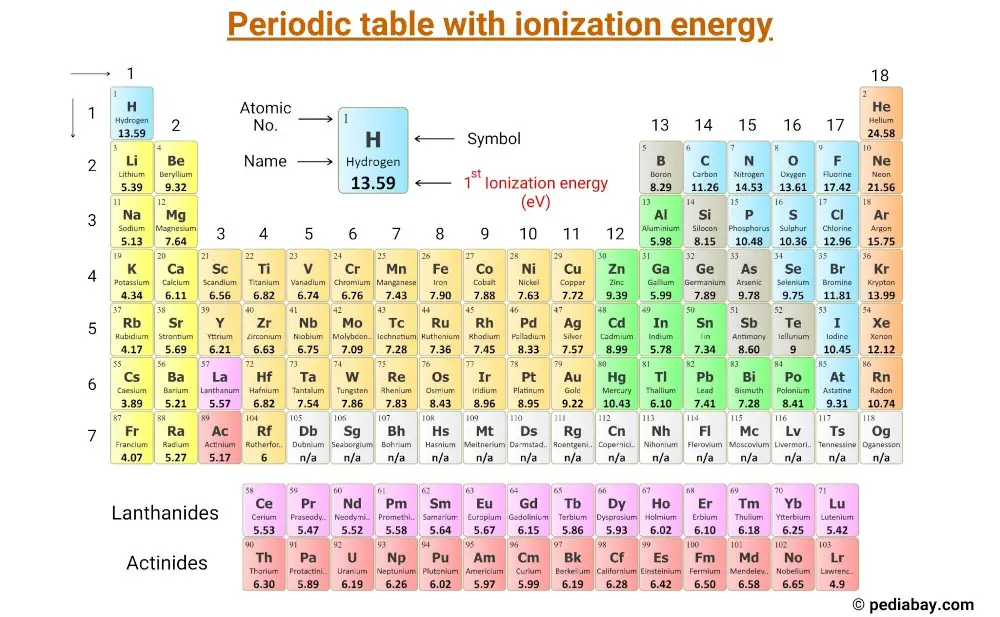

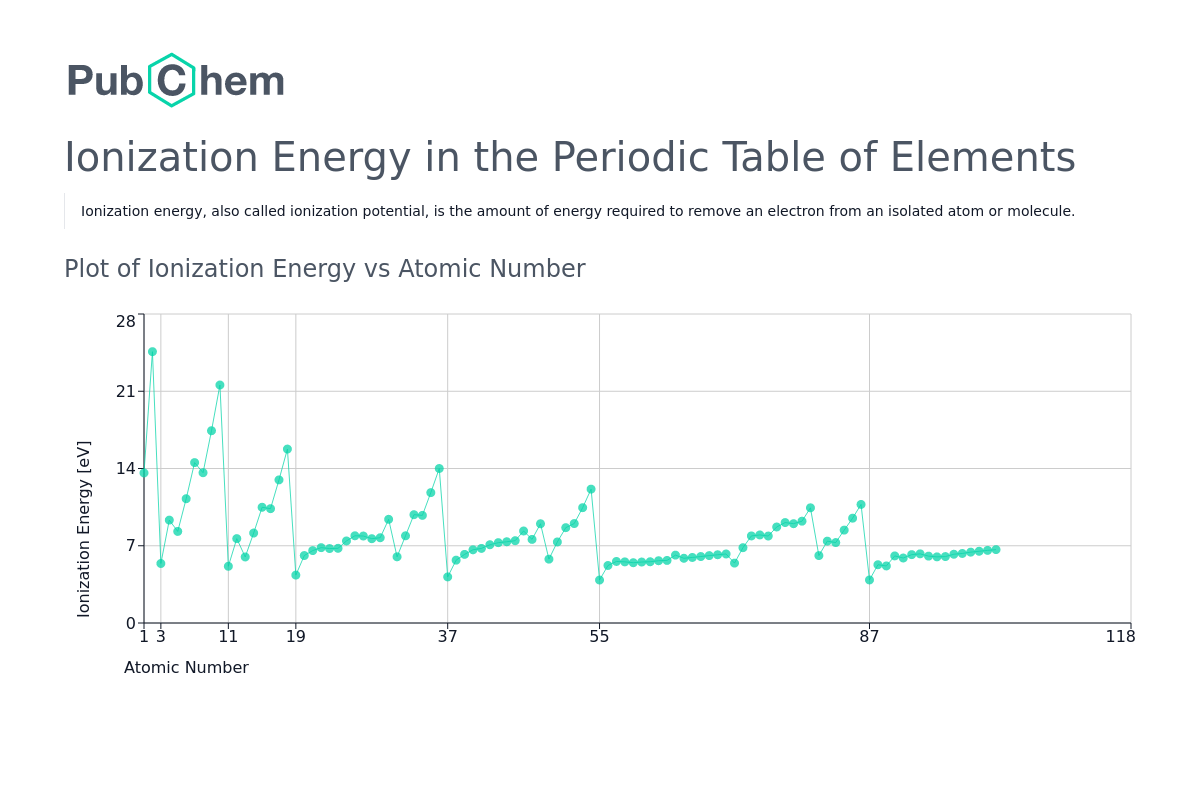

At the atomic level, ionization hinges on quantum mechanics and energy thresholds. Atoms consist of a nucleus surrounded by electrons occupying energy levels. Ionization occurs when energy exceeds the electron’s binding potential—known as the ionization energy.For hydrogen, the first ionization energy is 13.6 electron volts (eV), the energy needed to strip its single electron.

Photoionization exemplifies this principle. When a photon with energy exceeding the binding threshold strikes an atom, it excites the electron beyond escape, liberating it.

This principle enables photovoltaic cells, where sunlight-induced ionization generates electric current. Similarly, in gas discharge lamps, electric current accelerates electrons, colliding with gas atoms to ionize them and produce light. The process distinguishes plasma from neutral gas—a state where matter becomes highly conductive and reactive.

“Ionization transforms matter’s behavior from insulating and stable to dynamic and interactive,” clarifies Dr. Torres, “revealing the power locked in atomic structure.”

Collisional ionization depends on kinetic energy. In plasmas, electrons accelerated by electric fields collide with neutral atoms, transferring momentum and ejecting electrons.

This mechanism sustains ionized gases in stars, neon signs, and semiconductor processing chambers. The ionization rate correlates strongly with temperature and density, forming the basis of plasma diagnostics in fusion research and industrial applications.

Safety and Environmental Considerations

While ionization enables remarkable technological progress, it demands careful handling due to inherent risks.Ionizing radiation—such as X-rays and gamma rays—can damage living tissue, causing cellular harm and increasing cancer risk. Consequently, occupational safety guidelines strictly regulate exposure through shielding, monitoring, and time-dose limitations. In consumer products, ionizers used in air purification must balance effectiveness with safe ion discharge levels rarely posing harm under normal use.

Environmental ionization, particularly from industrial emissions, raises concerns about air and water quality. Ozone and nitrogen oxides generated by plasma discharges or combustion contribute to smog and acid rain. However, modern ionization technologies increasingly incorporate control mechanisms—like catalyst-assisted ionization or precision beam targeting—to minimize unintended pollution.

Plasma-based wastewater treatment, for instance, breaks down pollutants efficiently without chemical residues, offering a cleaner alternative.

The Future of Ionization: Innovation at the Atomic Frontier

Emerging research continues to push ionization’s boundaries, integrating nanotechnology, quantum control, and environmental sustainability. Nanoionization—localized ion emission at the nanoscale—could revolutionize targeted drug delivery and microscale manufacturing.Quantum ionization techniques explore coherent control of electron dynamics, enabling ultra-precise atomic manipulation for next-gen quantum computing applications.

Beyond labs and factories, ionization promises breakthroughs in energy storage and cooling. Advances in plasma-based batteries exploit ion conduction for faster charge cycles, while quench plasmas offer efficient cooling methods in high-power electronics.

These developments reflect a broader trend: harnessing ionization not merely for conversion, but for control—directing energy at the atomic scale to solve global challenges in medicine, environment, and energy.

Ionization may remain unseen, but its influence is pervasive and profound. From lightning rolling across skies to microchips in our pockets, from healing with radiation to cleansing the air we breathe, ionization is the invisible engine driving progress.

As science deepens understanding and refines technology, the potential to use ionization safely, efficiently, and sustainably expands—illuminating a future where charged particles shape a better world.

Related Post

In-Depth: The Remarkable Chronicle of Chung Ka Yan

<strong>December 12th Mugshots Spot Light Jefferson County: A Snapshot of Justice in the Bluegrass State</strong>

Norah O’Donnell’s Weight Loss Journey: From Studio Lights to Strength and Self-Confidence

Tiffany Green: Redefining Innovation and Strategy in Modern Business