Ionic vs Molecular: The Fundamental Divide That Shapes Every Chemical Interaction

Ionic vs Molecular: The Fundamental Divide That Shapes Every Chemical Interaction

At the heart of chemistry lies a key distinction: ionic and molecular compounds represent two distinct paradigms of how atoms bond and interact. While both form the invisible framework of matter, their structural principles, formation mechanisms, physical properties, and real-world applications diverge sharply. Understanding the core differences between ionic and molecular compounds is essential for chemists, engineers, and even everyday users navigating materials science—from the salts we sprinkle on food to the pharmaceuticals that treat disease.

This exploration reveals not just how these substances differ, but why those differences matter profoundly across science and industry.

Ionic compounds emerge from the electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions—cation and anion—born when one atom donates electrons and another accepts them. This defined, directional bonding results in crystalline lattice structures that dominate materials like sodium chloride (NaCl) and potassium nitrate (KNO₃).

By contrast, molecular compounds form when atoms share electrons through covalent bonds, creating discrete molecules such as water (H₂O) or glucose (C₆H₁₂O₆). These molecules lack long-range ionic order and instead pack more loosely, dictating unique physical behaviors ranging from solubility to melting points. Structural Foundations:

The Science of Bonds and Lattices

Ionic bonding arises from complete electron transfer, governed by principles of charge balance and energy minimization.Metals typically lose electrons to become cations, while nonmetals gain electrons, forming anions. The resulting electrostatic force—described by Coulomb’s law—creates incredibly strong, non-directional bonds. In crystalline ionic solids, ions arrange in repeating three-dimensional lattices, maximizing attraction while minimizing repulsion.

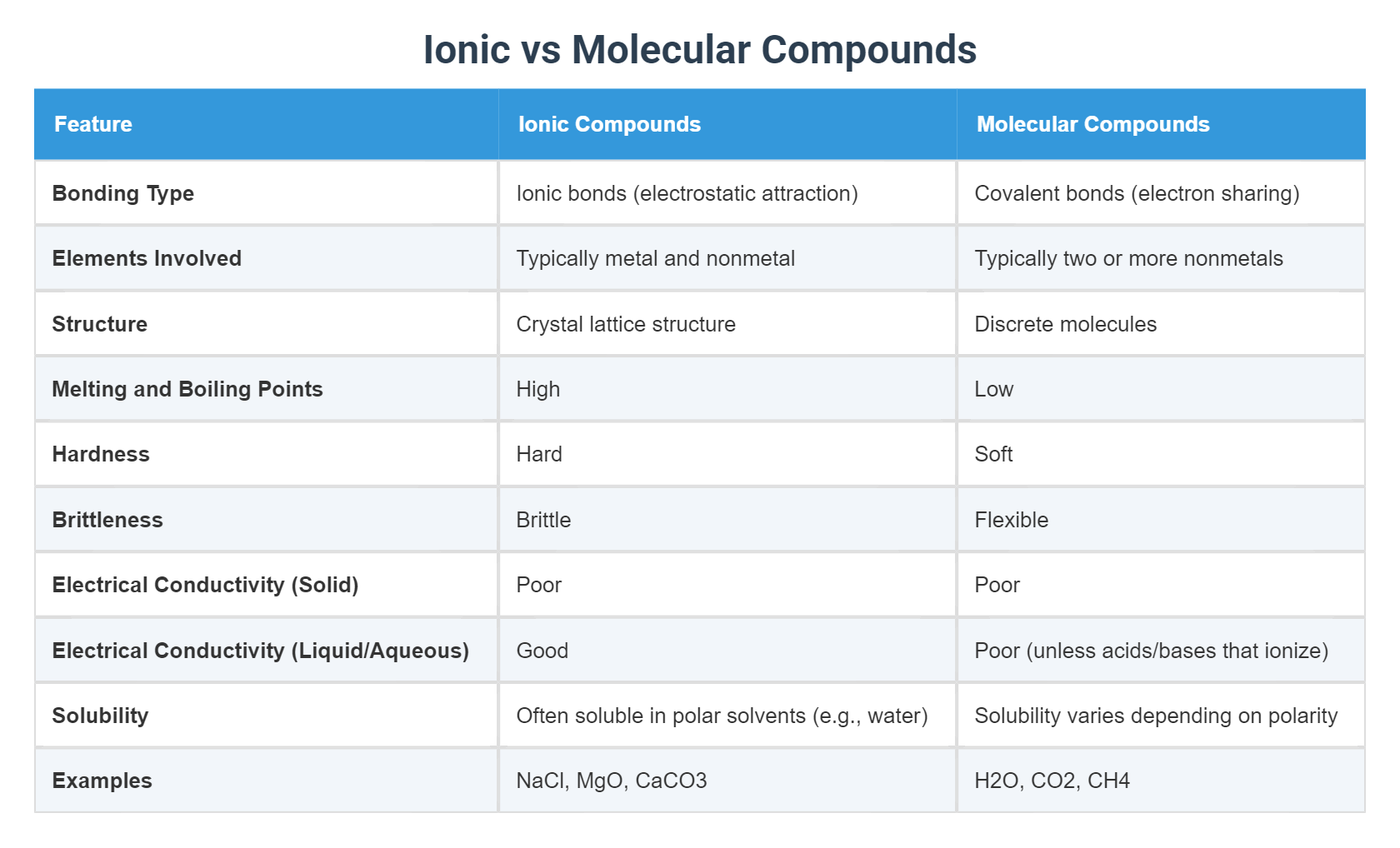

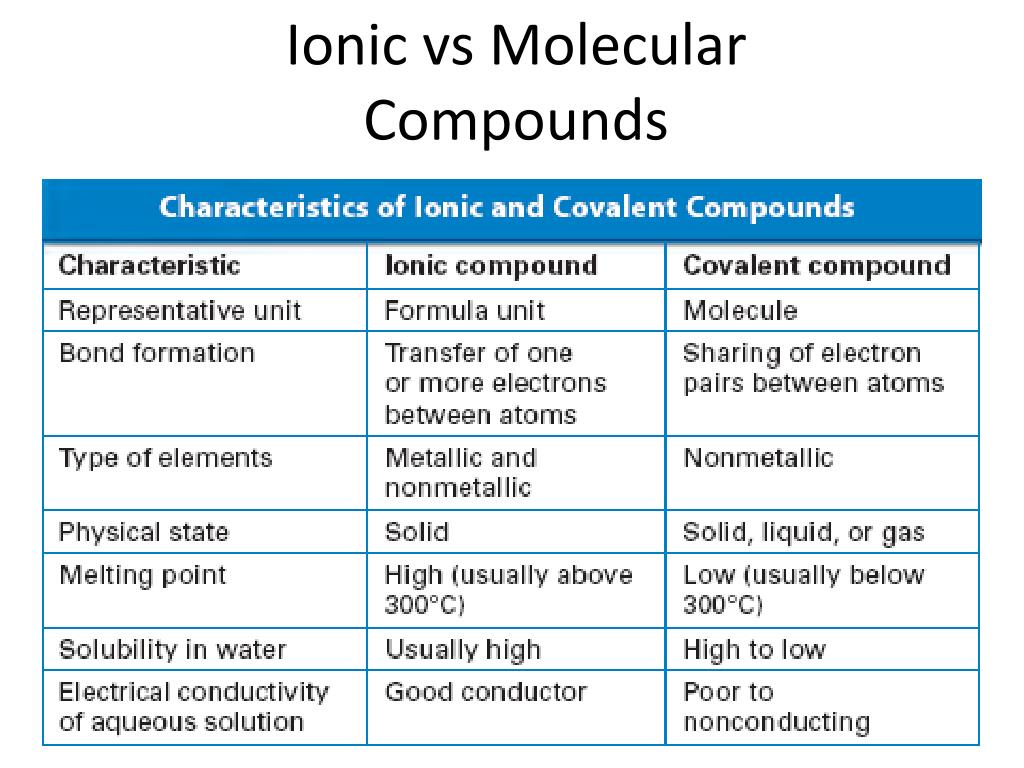

This structure confers rigidity and high melting points; for instance, NaCl melts at around 801°C despite its ionic lattice’s strength. Molecular compounds, by contrast, form through covalent sharing—either polar or nonpolar—yielding discrete structurally bound units. The strength and geometry of these bonds depend on valence electron distribution and molecular shape, as defined by VSEPR theory.

Molecular compounds often lack strong directional ordering, allowing molecules to stack or rotate in solids and liquids. This structural flexibility translates to lower melting and boiling points compared to ionic counterparts—such as acetone (C₃H₆O), which boils at just 56°C—due to weaker intermolecular forces like dipole-dipole interactions and London dispersion.

Formation Mechanisms and Environment Dependencies:

Where and How They Form

Ionic compounds emerge when electronegativity differences exceed a threshold—typically greater than 1.7—prompting electron transfer.This usually occurs between metals and nonmetals in aqueous or molten states, where ions freely migrate to assemble lattices. In nature, common ionic solids crystallize from evaporating saline water or cooling molten salts—processes that reflect the stability of ionic charge neutrality. Molecular compounds, conversely, form during reactions involving shared electron pairs, such as oxidation-reduction or synthesis pathways.

Organic molecules like ethanol (C₂H₅OH) form via covalent bond formation in chemical reactions under milder conditions. These compounds are best synthesized in liquid or gaseous environments, where molecules remain mobile enough to collide and bond. Environmental factors like temperature and solvent polarity heavily influence molecular stability and reactivity—critical considerations in industrial synthesis.

Physical Properties: Hardness vs. Flexibility The structural chasm between ionic and molecular compounds manifests clearly in physical properties. Ionic solids are famously brittle, rigid, and high-melting—due to their densely packed, charged lattices that resist shear but break cleanly along planes when stress is applied.

Their electrical conductivity is limited to molten or dissolved states, where mobile ions enable charge flow without molecular motion. Molecular compounds, especially those with weak intermolecular forces, tend to be softer, more malleable, and often thermal insulators. Soft solids like sugar (sucrose) or wax (mixtures of hydrocarbons) lack ionic rigidity, folding or flowing under moderate stress.

Their lower melting points make them ideal for applications requiring thermal sensitivity—such as in coatings or pharmaceuticals—where controlled phase transitions are essential.

Solubility and transport behavior further distinguish the two: ionic compounds dissolve readily in polar solvents like water, where ion hydration overcomes lattice energy, enabling ion mobility. This property underpins their use in electrolytes, batteries, and nutrient transport across biological membranes.

Molecular compounds, especially nonpolar ones like oils or gases (e.g., methane), often dissolve poorly in water due to mismatched intermolecular interactions but mix freely in organic solvents like ethanol or acetone.

Applications Across Science and Society:

From Salt Flakes to Sugar Cubes

The distinction between ionic and molecular compounds manifests in countless everyday and industrial contexts. In medicine, ionic salts like sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO₃) and intravenous saline deliver electrolytes directly into bodily systems, leveraging ionic solubility for rapid physiological action.Conversely, molecular compounds such as aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) or insulin—proteins with complex covalent structures—rely on molecular integrity for targeted, precise biological function. In materials science, sodium chloride delivers structure to table salt, while polymers—covalently bonded molecular chains—form plastics, fibers, and resins. The durability of ceramics and glasses (ionic) contrasts sharply with the flexibility of rubber (molecular), highlighting how bonding dictates end-use performance.

Industrial and Environmental Implications:

Manufacturing, Sustainability, and Beyond

Industrially, ionic compounds dominate

Related Post

Daniela Rajic Wiki Age Nationality Parents and Net Worth

Revealing the Confidential Sphere: The Question for Taylor Townsend Husband Condition