Intermolecular Forces Ranked: From Unbreakable Bonds to Fleeting Interactions

Intermolecular Forces Ranked: From Unbreakable Bonds to Fleeting Interactions

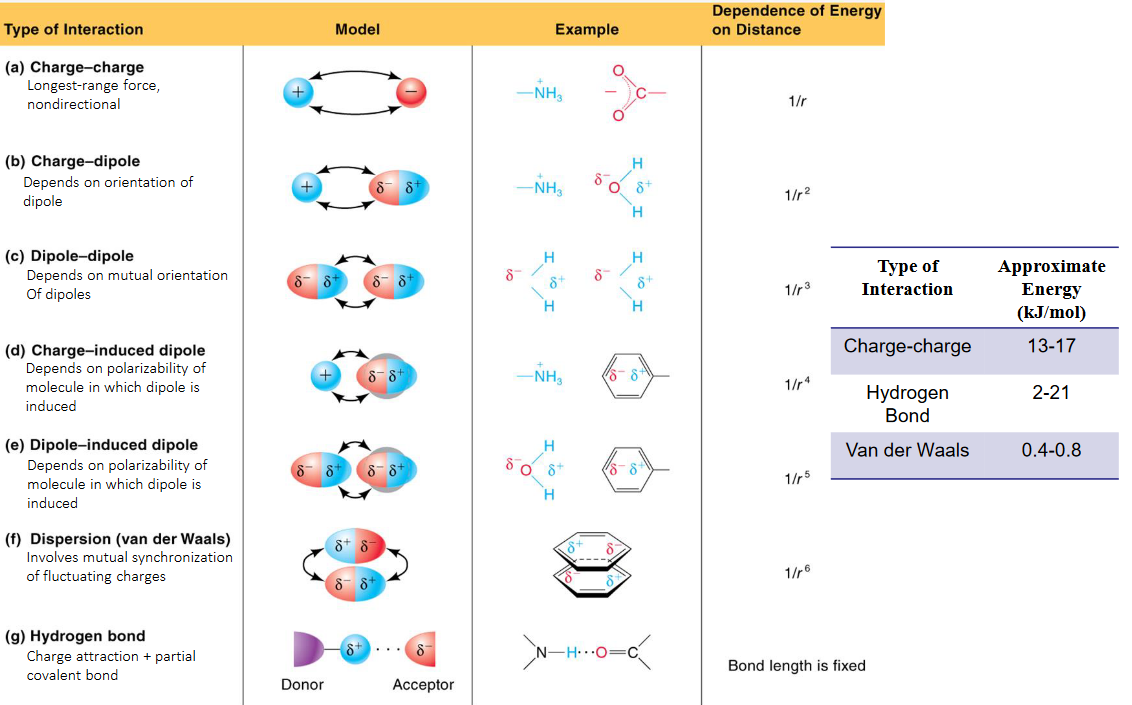

From the molecular grip that keeps water in liquid form at room temperature to the delicate push-pull that lets water evaporate, intermolecular forces govern the physical behavior of matter. These forces—spanning the spectrum from the extraordinarily strong to the nearly invisible—dictate whether a substance boils at room temperature or remains a gas, whether a polymer stays rigid or melts, and how solvents dissolve solutes. Understanding their hierarchy—strongest to weakest—provides essential insight into chemistry’s foundational principles, influencing everything from industrial processes to biological function.

At the top of this force ladder stands hydrogen bonding, a uniquely powerful interaction arising from the strong electrostatic attraction between a hydrogen atom bonded to a highly electronegative atom—such as nitrogen, oxygen, or fluorine—and another electronegative atom nearby. This bond typically ranges from 50 to 300 kilojoules per mole, affording substances remarkable cohesion and structural integrity. Water exemplifies hydrogen bonding’s impact: its high boiling point of 100°C at atmospheric pressure stems directly from these intermolecular attractions, which are far stronger than typical dipole-dipole forces but still outmatched by covalent bonds within molecules.

“Hydrogen bonds are like molecular Velcro—they’re strong enough to hold water together but dynamic enough to allow liquid flow,” explains Dr. Elena Marquez, a physical chemist at Stanford University. In biological systems, hydrogen bonding stabilizes DNA’s double helix and maintains protein folding, underscoring its role as nature’s architectural glue.

Hydrogen Bonding: Nature’s Most Potent Intermolecular Glue

Those hydrogen bonds form when protium, the simplest isotope of hydrogen, becomes covalently bonded to oxygen, nitrogen, or fluorine. Because these atoms carry a significant partial positive charge, they pull electrons from nearby hydrogen atoms in neighboring molecules, creating a directional, short-range attraction. While single hydrogen bonds deliver measurable effects—such as water’s elevated surfaces tension—dense networks amplify cohesion: ice’s resistance to compression and ethanol’s higher boiling point compared to methane derive from this intermolecular synergy.Dipole-Dipole Interactions: Polar Molecules in Tight Grip

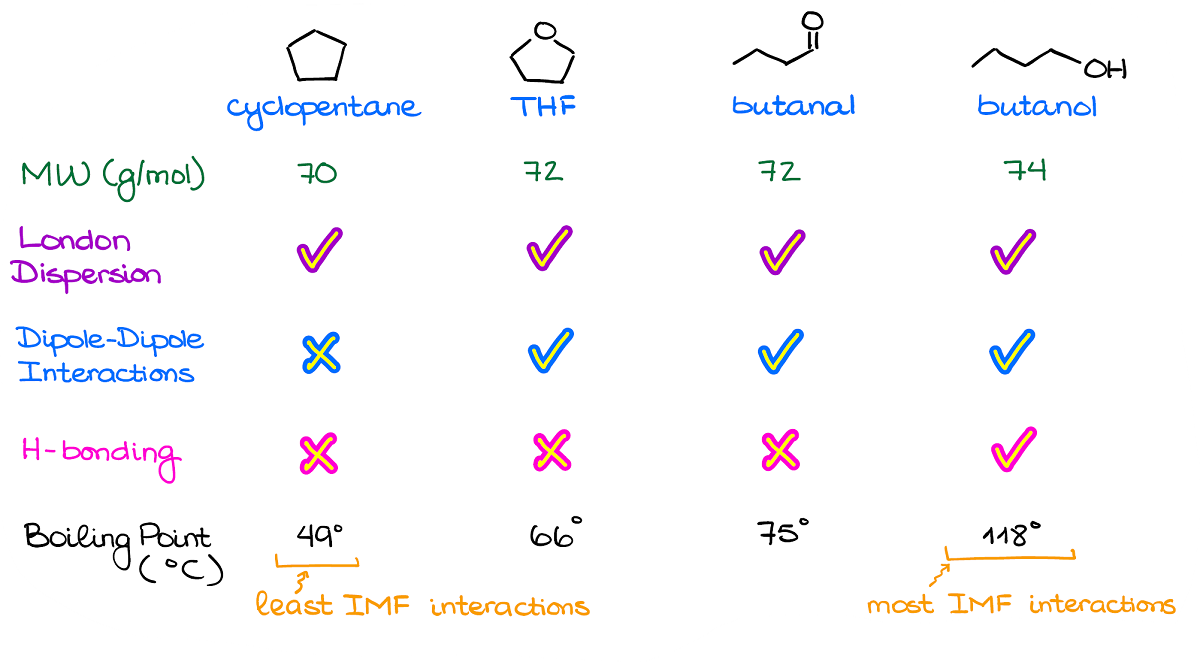

Beneath hydrogen bonds lie dipole-dipole interactions, where permanent molecular asymmetry creates regions of partial positive and negative charge. These forces arise naturally in polar molecules like hydrogen chloride or acetone, where electronegativity differences induce charge separation. Although weaker—averaging 5 to 20 kJ/mol—dipole-dipole attractions significantly influence physical properties: they maintain liquid states in common solvents and regulate solubility by enabling “like dissolves like” behavior.Still, their reach is limited by molecular size and flexibility, explaining why polar liquids often have relatively low boiling points compared to hydrogen-bonded substances. “Dipole interactions are the bridge between electrically neutral and charged worlds,” notes Dr. Rajiv Patel, a molecular physicist.

“They matter a lot, but only within polar systems.”

Scope and Complexity of Dipole-Dipole Attractions

Unlike hydrogen bonding’s specificity, dipole-dipole forces operate broadly among polar molecules, yet remain too weak to sustain liquid cohesion in less polar or large nonpolar substances. Their effectiveness diminishes with increasing molecular complexity, as long carbon chains

Related Post

Beverly Hills Cop 3 Cast: Still Ich bones to the Law, Decades Later

Alton Brown Good Eats Bio Wiki Age Wife Shows and Net Worth

Experience The Excitement Of Methstreams Boxing A Comprehensive Guide Empire, Fitness & Nor Ko in Books

Why Is Deadpool Rated R? Unpacking the Rating and Its Cultural Impact