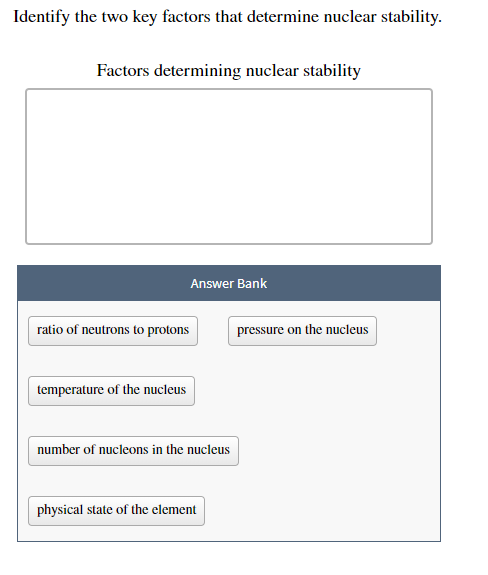

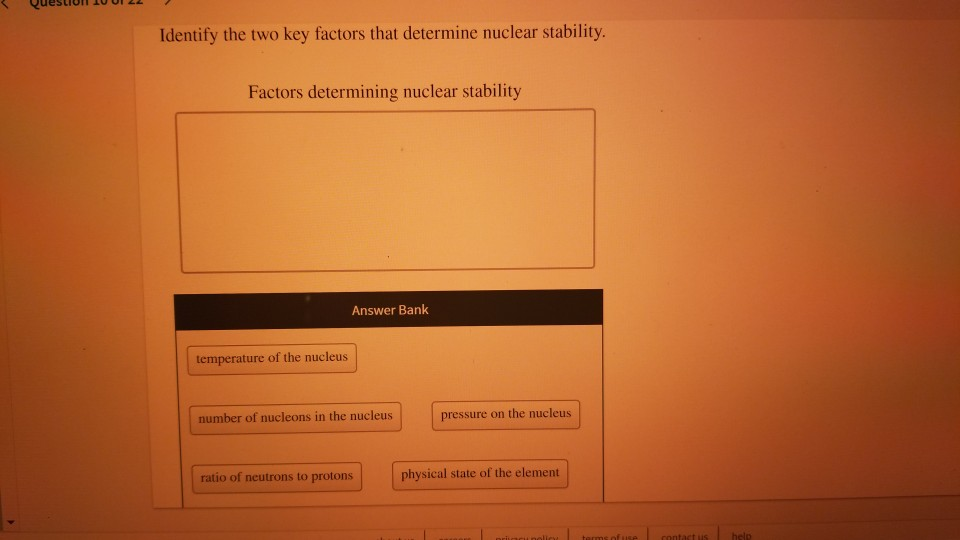

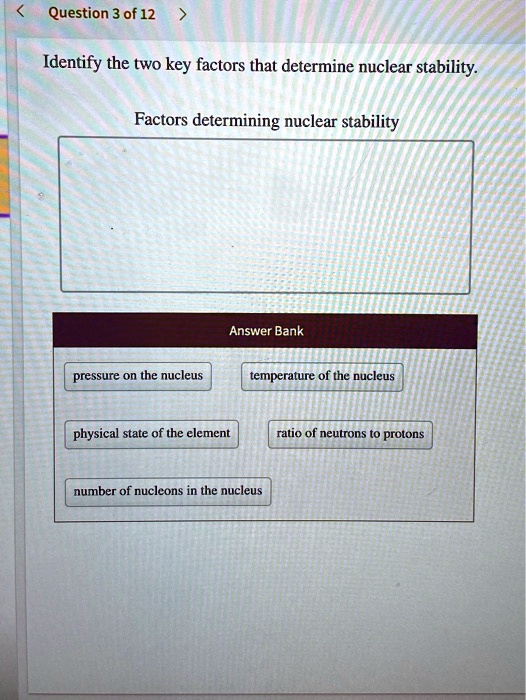

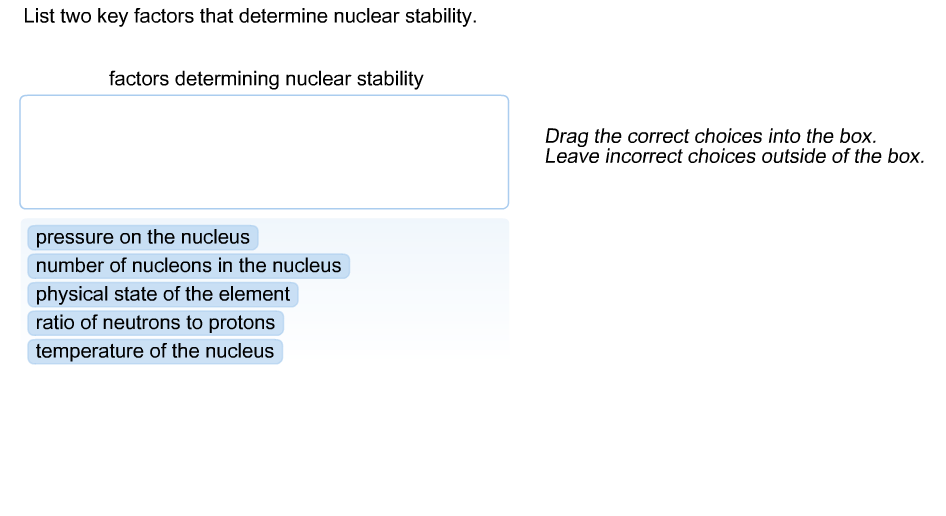

Identify The Two Key Factors That Determine Nuclear Stability

What Truly Makes Atomic Nuclei Stable? Two Unveiled Key Forces Behind Nuclear Strength – Nuclear stability is the silent engine powering stars, enabling medical imaging, and shaping the fusion dreams of tomorrow. While hundreds of nuclear interactions unfold at subatomic scales, only two fundamental factors govern whether a nucleus remains intact or shatters in a split.

These atomic thresholds are not mere scientific curiosities—they are the bedrock upon which nuclear energy, radar technology, and even the life cycle of elements rests. Understanding these forces reveals why some isotopes glow silently in detectors while others explode in devastating fission, and why certain elements in nature endure while others vanish within milliseconds.

The first key determinant is the **balance of nuclear binding energy and the proton-neutron ratio**, governed by the strong nuclear force and quantum mechanics. At the core lies the strong force, the most powerful fundamental interaction, binding protons and neutrons into cohesive nuclei.

Without it, electrostatic repulsion between positively charged protons would tear apart the cluster within nanoseconds. “The strong nuclear force overcomes Coulomb repulsion at short ranges—typically within 1–3 femtometers,” explains Dr. Elena Rostova, a nuclear physicist at CERN.

“This force resists deformation, stabilizing nuclei against disintegration, but its effectiveness sharply declines beyond this distance, creating a fragile equilibrium dependent on nuclear composition.” The ratio of neutrons to protons further fine-tunes this stability. For lighter elements like helium (Z=2), a 1:1 ratio suffices, but as mass increases—say in iron (Z=26) at 1:1.05—the extra neutrons provide extra strong-force binding without overloading repulsion. Yet past zinc (Z=52), the neutron excess grows to approximately 1.6:1, as additional neutrons act as “glue” to counteract escalating proton repulsion.

Too many neutrons, however, introduce instability through neutron-rich decay modes, illustrating the delicate dance required for longevity.

The second pivotal factor is the **nucleon separation energy and quantum shell effects**, the quantum mechanical framework that organizes protons and neutrons into discrete energy levels. The separation energy measures how much energy is needed to remove a single nucleon from the nucleus without breaking it apart. Nuclei with high separation energy per nucleon are inherently stable because internal forces resist displacement—like a securely welded frame.

“Think of nucleons as players in a tightly packed cubicle, each influencing and defending their space through quantum rules,” notes Dr. Rostova. “When nucleons fill full energy shells—akin to filled locker rows—the nucleus gains extra stability, much like atoms with noble electron configurations.” This nuclear shell model explains why isotopes of lead (Z=82), near the band of stability, resist decay more than neighbors with unpaired nucleons.

Moreover, even lightweight nuclei reveal shell effects: oxygen-16, with a closed shell configuration (8 protons and 8 neutrons), achieves exceptional stability, resisting spontaneous emission far longer than neighboring isotopes.

The interplay between binding energy and quantum shell structure defines the nuclear landscape. Consider uranium-238, a heavy, naturally occurring isotope: its stability hinges on both its neutron-rich, high separation energy profile and the relativistic motion of its densely packed nucleons, which create a resilient, though ultimately decaying, form. In contrast, helium-4—with its tightly bound, filled nuclear shell—remains stable indefinitely under standard conditions, having burned through its fusion potential long ago.

Fissionable elements like plutonium-239 exploit this duality; their neutron-rich shells allow binding energy to dip dangerously close to decay thresholds, enabling catastrophic release when stability is breached.

The two factors—nuclear binding dynamics and quantum shell organization—form the axis of stability, dictating whether a nucleus lives or explodes. These principles underpin practical applications: from uranium enrichment for reactors to isotopic dating that hinges on predictable decay rates. As global interest in advanced nuclear technologies grows, mastering these forces offers more than scientific insight—it guides safer, smarter engineering.

Understanding what holds nuclei together, and when it fails, transforms theoretical physics into life-altering technology, reminding us that even the smallest atomic components carry profound, far-reaching influence.

Binding Energy and the Stural Integrity of Atomic Nuclei

At the heart of nuclear stability lies the binding energy—the immense force holding protons and neutrons together against their mutual repulsion and quantum instability. This energy, measured in millions of electronvolts per nucleon, reflects the net work needed to disassemble a nucleus into free nucleons. A higher binding energy per nucleon signifies a tightly bound, resilient nucleus.Light elements like hydrogen and helium achieve moderate values (~1–7 MeV), ideal for stellar fusion. Heavier nuclei peak near iron (Z=26), with ~8.8 MeV/nucleon, representing the maximum binding efficiency before increasing Coulomb repulsion overwhelms the strong nuclear force. “Binding energy is the nucleus’s structural backbone—it determines whether it resists decay or surrenders to instability,” explained Dr.

Rostova. “The transition from stability to fission often begins when binding energy plateaus or declines, especially beyond atomic numbers Z=82, where relativistic effects alter nuclear behavior.” This principle explains why small, medium, and heavy nuclei exhibit distinct stability profiles and decay mechanisms, forming the foundation of nuclear physics.

Quantum Shell Structure: A Hidden Order in the Subatomic World

Beyond sheer binding energy, the quantum arrangement of nucleons introduces an additional layer of stability rooted in nuclear shell theory. Analogous to electron shells in atoms, nucleons occupy discrete energy levels within the nucleus, with closed shells conferring enhanced stability.Isotopes with fully filled proton or neutron shells—known as “magic numbers”—resist fission or radioactive decay more tenaciously. Oxygen-16, with 8 protons and 8 neutrons forming both the proton and neutron shells, exemplifies this nuclear nobility: it persists with remarkable longevity, a rarity among radioactive species. “Closed shells create a kind of nuclear immunity, where nucleons symmetrically fill energy levels, minimizing excess energy and reducing decay likelihood,” Dr.

Rostova elaborated. This quantum order helps explain why certain isotopes dominate in nature and why others—like technetium-99—exist only fleetingly as synthetic byproducts. Together, binding energy and shell effects create a dual safeguard: the nucleus holds together through force, yet retains a hidden resilience shaped by quantum architecture—two inseparable forces steering every atom’s fate.

Related Post

How Long To Go To Mars: The Unrelenting Clock Behind Human Interplanetary Travel

Crawford Ray Funeral Home in Canton, NC: When Death Didn’t Follow the Script This Town Expected

Sierra Skye Onlyfans Scandal Unfolds: Experts Unravel The Shocking Fallout Behind the Mattress of Controversy

Frank Marzullo Weather Fox19 Bio Wiki Age Height Wife Announcement Salary and Net Worth