How the Electron Transport Chain Transforms Energy: The Reactants and Products Powers the Cell Car convergence Heat Recovery.

How the Electron Transport Chain Transforms Energy: The Reactants and Products Powers the Cell Car convergence Heat Recovery.

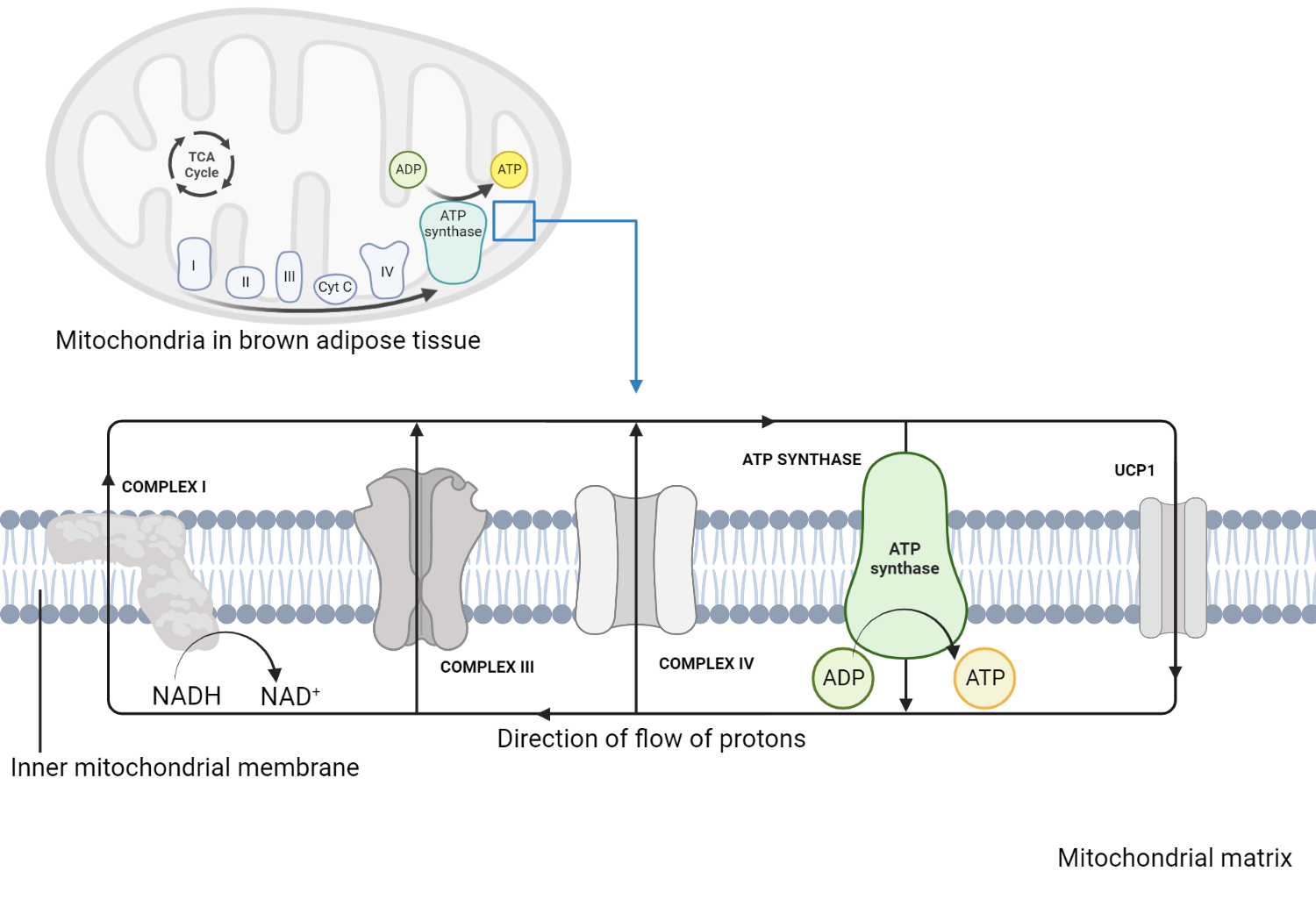

At the heart of cellular energy production lies the electron transport chain (ETC)—a molecular assembly line embedded in mitochondrial inner membranes that converts biochemical energy into usable adenosine triphosphate (ATP) with remarkable efficiency. This intricate system relies on a carefully orchestrated flow of electrons derived from metabolic fuels, ultimately reducing molecular oxygen while generating key high-energy products. Understanding the reactants and products of the ETC reveals not only the mechanics of ATP synthesis but also the elegant economy of energy transformation within living cells.

The primary reactants fueling the electron transport chain are electrons donated by reduced coenzymes—specifically NADH and FADH₂—produced in earlier stages of cellular respiration such as glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, and pyruvate dehydrogenase. NADH carries high-energy electrons normally bound to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD⁺), while FADH₂, derived from FAD (flavin adenine dinucleotide), delivers electrons from succinate dehydrogenase. “Each NADH feeds electrons into complex I, and each FADH₂ into complex II,” explains biochemist Dr.

Elena Vargas, “making FADH₂ a secondary but vital contributor to ATP output.” These electron donors undergo oxidation at the ETC’s starting point, initiating a cascade that releases energy stored in redox bonds. The electron transport chain itself comprises four multi-protein complexes (I to IV) embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane, paired with mobile electron carriers: ubiquinone (coenzyme Q) and cytochrome c. As electrons jump through the complexes—from NADH via complex I, then coenzyme Q, through complex III (cytochrome bc₁), followed by another transfer to cytochrome c, and finally to complex IV—the buildup of electrical potential creates proton gradient energy.

This gradient, often described as a "proton-motive force," drives ATP synthesis not through combustion, but via a precision-engineered proton flux.

The key products of the electron transport chain are two of the most essential biological molecules: ATP and water. During electron transfer, the energy released phosphorylates adenosine diphosphate (ADP) into ATP via ATP synthase, a molecular turbine powered by proton flow back into the mitochondrial matrix.

“ATP synthesis isn’t a chemical output but a physical consequence of redox energy conversion,” notes Professor Rajiv Mehta, senior researcher in mitochondrial bioenergetics. For each full turn of ATP synthase, roughly three protons pass through, producing three phosphate bonds—resulting in the rapid regeneration of ATP, the universal energy currency. Water emerges as the final, irreplaceable product at complex IV, where electrons from cytochrome c combine with molecular oxygen (O₂) and protons to form two water molecules.

“Oxygen is the last electron acceptor in this chain—a role so critical that its absence halts respiration,” underscores Mehta. Without the continuous flow of electrons supplied by NADH and FADH₂, oxygen remains unbound, preventing the chain from functioning and effectively choking energy production.

Each turn of the electron transport chain consumes one molecule of NADH and one of FADH₂, producing approximately 2.5 ATP from NADH and 1.5 ATP from FADH₂—though actual yields vary due to shuttle mechanisms and proton leak.

The efficiency of this system derives from the strategic separation of electron acceptors and proton pumping, ensuring energy is not wasted but harnessed. This precision enables cells to maintain high ATP output—up to 32 to 34 molecules per glucose—making the ETC central to aerobic life.

Beyond energy metabolism, the ETC’s design reflects evolutionary optimization.

Reactants and products are precisely balanced to sustain steady-state respiration, minimizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) that could damage cells. “Cells don’t just pass electrons—they manage redox balance,” Vargas clarifies. “The chain’s architecture ensures controlled electron flow, minimizing harmful leakage and maximizing ATP yield.” This balance reveals how electron transport is not merely a chemical process, but a masterful integration of electron chemistry, proton dynamics, and structural function.

In summary, the electron transport chain’s reactants—NADH and FADH₂—deliver high-energy electrons, while its products, ATP and water, fuel cellular functions and support aerobic life. With each electron drop, the ETC converts the redox energy of metabolism into life-sustaining power, governed by physical laws and refined by evolution. The chain’s elegance lies not in complexity alone, but in its efficiency: a seamless transformation from molecular fuel to usable energy, underscoring why the transport of electrons remains one of biology’s most critical and sophisticated achievements.

Related Post

Bobby Fish Has Not Signed A Contract With IMPACT Wrestling

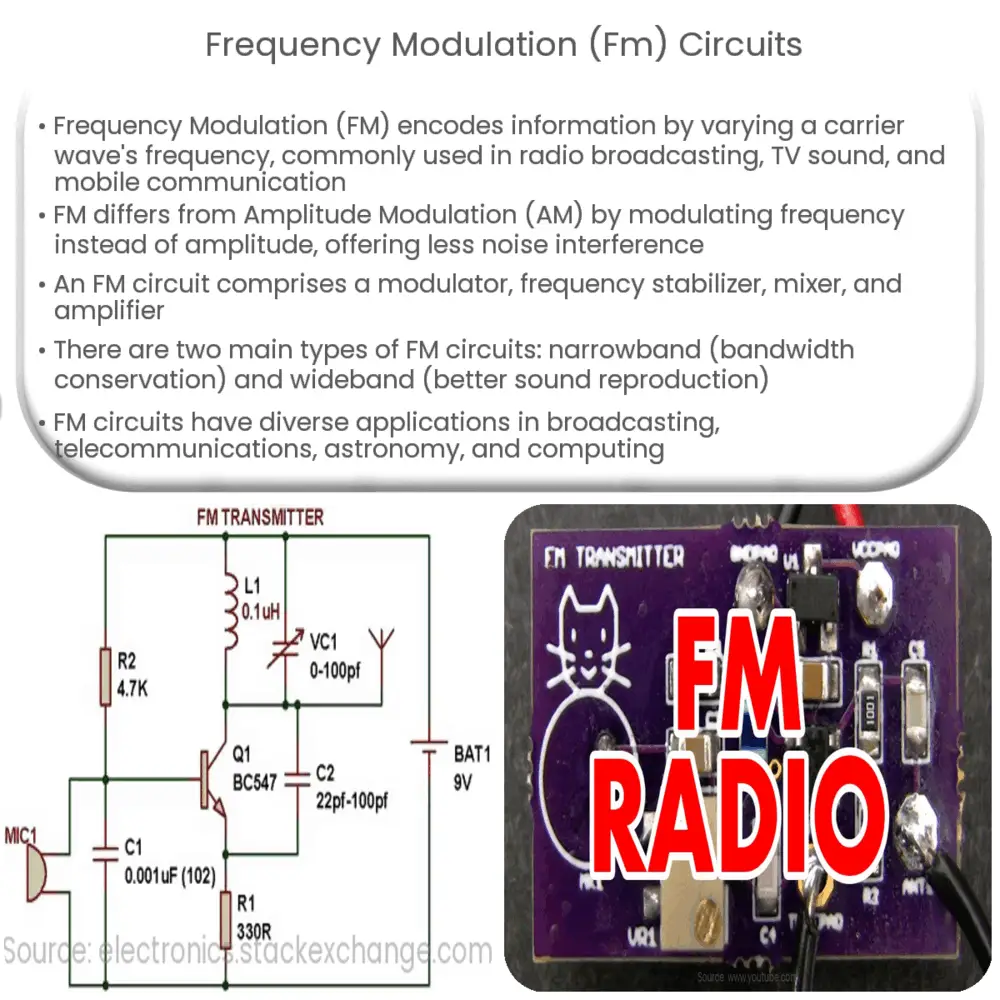

Unlocking FM 5.0: The Next Evolution in Frequency Modulation Technology

<strong>Excel Definition: The Unseen Engine Powering Business Intelligence</strong>

The Transformative Rise of Nii San: From Niche Innovator to Industry Trailblazer