Global and Local Winds: Decoding the Winds of Change Through the Venn Diagram Lens

Global and Local Winds: Decoding the Winds of Change Through the Venn Diagram Lens

From the sweeping Tibet Plateau to the whispering coastal breezes of Maine, wind shapes the planet’s atmosphere in profound and often invisible ways. While winds flow across the globe, driven by vast pressure systems and Earth’s rotation, localized patterns—carved by mountains, oceans, and terrain—create microclimates that influence daily life, agriculture, and ecosystems. Understanding the dynamic relationship between global and local winds reveals not just atmospheric mechanics, but also how climate systems unfold across scales.

This analysis, visualized through a clear Venn diagram, explores the overlapping domains of planetary-scale winds and regional phenomena, exposing both shared forces and unique signatures across Earth’s diverse landscapes.

Global winds—steady, large-scale air currents moving across continents and oceans—are the lungs of Earth’s climate system. Driven primarily by differential solar heating and the Coriolis effect, these winds form predictable bands invisible to the naked eye but powerful enough to steer hurricanes, sustain monsoons, and stabilize temperature extremes.

At opposite ends of the scale, local winds are transient and hyper-reactive, shaped by immediate geography such as valleys, coastlines, and thermal contrasts between land and sea. Though distinct in scope, these two spheres frequently intersect, creating compound wind patterns that defy simple categorization.

The Global Wind Framework: Planetary-Scale Drivers

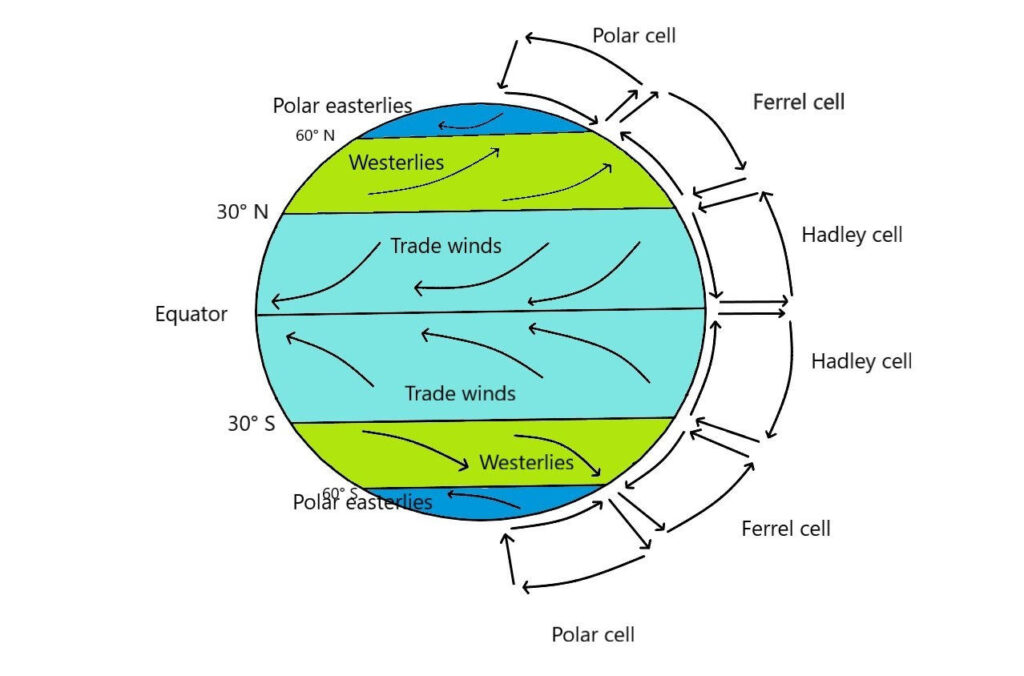

Global winds operate on a grand scale, guided by fundamental atmospheric dynamics and hemispheric physics. These wind systems emerge from three key factors: - **Incoming solar energy**: Equatorial regions absorb more sunlight than polar zones, creating a temperature gradient that initiates air movement from high to low pressure.- **Coriolis effect**: Earth’s rotation deflects air masses, dividing global winds into four primary bands. - **Pressure cell organization**: The Hadley, Ferrel, and Polar cells structure winds into predictable zones: the trade winds near the equator, westerlies at mid-latitudes, and polar easterlies toward the poles. These global currents are not static.

Seasonal shifts—like the migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone—alter their strength and direction, influencing weather patterns from the Amazon to Southeast Asia. As marine meteorologist Dr. Elena Marquez explains: “Global winds are the backbone—they set the stage for large-scale storm tracks and seasonal transitions, but they rarely dictate local gusts.”

Understanding global winds requires recognizing three primary lieutenants: the horse latitudes, the doldrums, and the mid-latitude westerlies.

Together, they create stable corridors that transport heat, moisture, and energy across the planet. The trade winds, blowing consistently northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and southeast in the South, drive ocean gyres and underpin tropical storm formation. Meanwhile, the westerlies dominate weather in temperate zones, steering cyclones and shaping precipitation distribution.

Local Winds: Microclimates Forged by Terrain and Surface

In contrast to the steady rhythm of global winds, local winds arise from rapid, localized interactions between atmosphere and environment.Their formation hinges on surface features that disrupt airflow, generating thermal gradients, pressure differences, or wind funnelled through narrow passes. These winds manifest in familiar forms: sea breezes that cool coastal cities, mountain winds that drive valley climates, and downslope katabatic winds that accelerate with startling speed.

Three defining characteristics distinguish local winds: - **Thermal drivers**: Land heats and cools faster than water, creating daily cycles—like onshore breezes during the day and offshore flows at night.

- **Topographic influence**: Mountain ranges and valleys channel, accelerate, or block wind, producing legendary phenomena such as the Santa Ana winds or the Föhn effect. - **Maritime contrasts**: Coastal zones experience pronounced wind shifts due to differing heat capacities between land and sea, moderating extremes and shaping regional weather.

Consider the Pacific Northwest’s Chinook winds: warm, dry air flows eastward from the Rocky Mountains during winter, dramatically raising temperatures in hours. Or the Morning Glory clouds over Australia, where hot, humid air swalshes through low-lying corridors to deliver rare but intense wind bursts.

These examples show how topography and surface heating inject local variability into the global pattern, crafting distinct microclimates.

The Venn Diagram of Global and Local Winds: Where Forces Intersect At the intersection of global and local wind systems lies a dynamic Venn diagram where planetary-scale patterns meet terrain-driven specifics. The overlapping zone is where broad atmospheric forces are filtered through local geography, amplifying or modifying their effects. This convergence creates unique wind regimes that neither global nor local wind alone could produce.

Two critical overlap points define this intersection: 1. **Coastal wind systems**: Global prevailing winds interact with local land-sea temperature contrasts to produce reliable sea and land breezes. Over Charleston, South Carolina, for instance, the onshore breeze of afternoon warms the coast while effectively stabilizing urban heat.

2. **Mountain-valley circulations**: The global Hadley cell drives regional air rising on windward slopes and descending in leeward basins, creating predictable valley winds enriched by local heating and cooling cycles. The Alps’ föhn winds exemplify how this global motion is intensified by terrain, bringing sudden warmth and dryness to alpine valleys.

This synergy transforms global momentum into localized power. Weather historian Dr. Raj Patel notes: “Where global systems meet local towers, winds stop being abstract forces and become lived experiences—shaping harvests, flights, and even architecture.”

Map examples from around the world reinforce this fusion.

Along India’s west coast, the global southwest monsoon interacts with the Western Ghats’ steep terrain to generate torrential rains unique to the region. In the Andes, cold polar winds collide with warm, moist easterlies, triggering fiercely localized downslope winds that influence everything from glacial melt to wildfire risk. These cases underscore how global patterns, when constrained and intensified by local geography, generate distinctive weather phenomena with profound regional impact.

Quantifying the Coexistence: Data and Patterns

Scientific analysis reveals measurable differences—and powerful complementarity—between global and local wind regimes.Satellite observations, anemometer networks, and atmospheric modeling show that while global winds follow consistent general trajectories, local winds exhibit higher variability and stronger dependency on immediate conditions. For instance: - Global winds contribute to long-term climate norms, with averages like the trade winds sustaining 10–15 km/h speeds across ocean basins. - Local winds often peak at 10–30 km/h but fluctuate hourly or seasonally, with extremes exceeding 100 km/h in phenomena like the Chinook or Santa Ynez winds.

- Microclimates shaped by local winds can differ significantly from nearby global averages—sometimes by 5–10°C in temperature or 30% in humidity. This duality highlights the necessity of studying both scales: global winds explain large-scale predictability, while local winds account for the nuanced, on-the-ground realities affecting ecosystems and human activity.

Implications: From Weather Forecasting to Climate Resilience Understanding the Venn intersection of global and local winds is not merely an academic exercise—it directly informs practical applications.

Meteorologists rely on combined models to improve short-term forecasts and long-range climate projections. Urban planners use knowledge of local wind patterns to design ventilation-friendly buildings, mitigate heat island effects, and site renewable energy installations. Agricultural communities depend on accurate wind predictions tied to both global shifts and local microclimates to manage irrigation, planting, and harvest timing.

Climate change further amplifies the importance of this integration. As global warming alters pressure systems and intensifies extreme weather, localized wind disruptions—such as stronger sea breezes or more frequent katabatic surges—emerge as critical adaptation indicators. Recognizing how global trends interact with fragile regional systems enables better preparedness and resilience.

The Winds of Synergy: A Call for Holistic Understanding The global and local wind Venn diagram reveals more than a scientific abstraction—it captures the layered complexity of Earth’s atmospheric dance. From the steady horse latitudes to the fleeting mountain gusts, wind operates across scales, each shaping the planet’s climate tapestry. Without global winds, local patterns lack coherence; without local winds, planetary patterns lose their tangible, lived expression.

Together, they form an intricate, interactive system where large-scale forces meet intimate geography, producing weather as diverse as the world itself. This integrated perspective transforms wind from an invisible element into a powerful lens—illuminating how climate operates not in isolated bursts, but in recursive, interconnected flows. The future of weather science, climate adaptation, and environmental stewardship depends on honoring both the vast and the minute, recognizing that wind, in all its forms, remains one of nature’s most dynamic storytellers.

Related Post

Marlo Hampton Bio Wiki Age Height Husband House Nephews Kids and Net Worth

Whats Lil Yachtys’ Real Name? Unveiling the Human Behind the Iconic Moniker

Are The Yankees Playing Today? Current Game Status and What Fans Need to Know

Fútbol Club Juárez: The Tangible Fire of Ciudad Juárez’s Fußball Soul