Fungi: Masters of the Eukaryotic Domain — Unraveling the True Nature of These Complex Organisms

Fungi: Masters of the Eukaryotic Domain — Unraveling the True Nature of These Complex Organisms

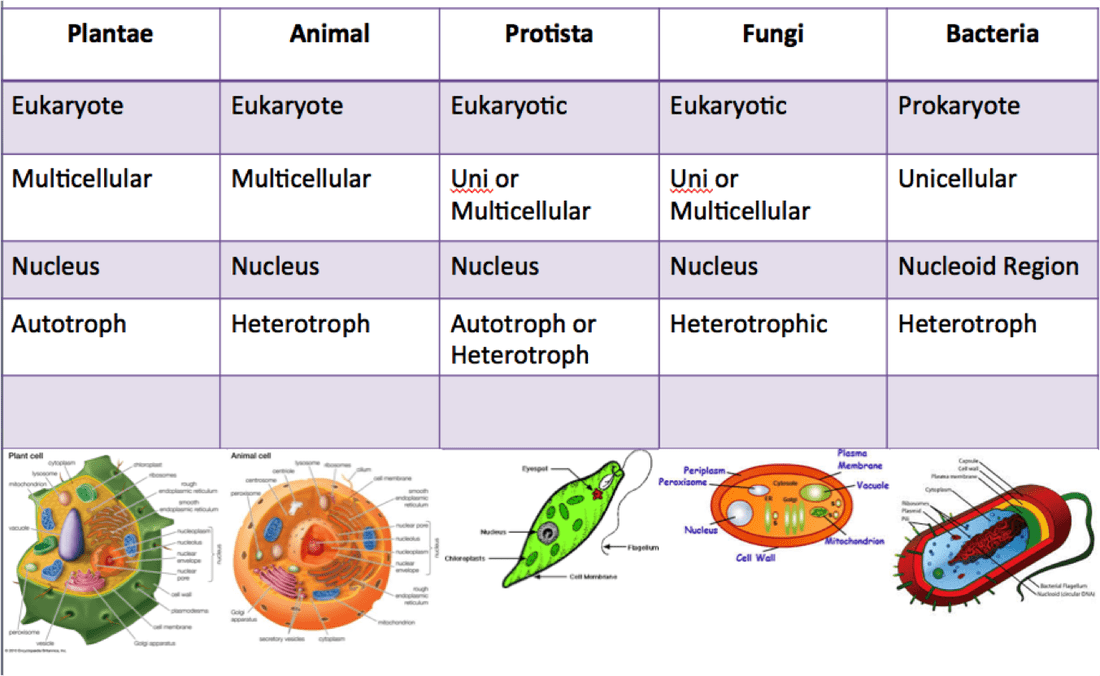

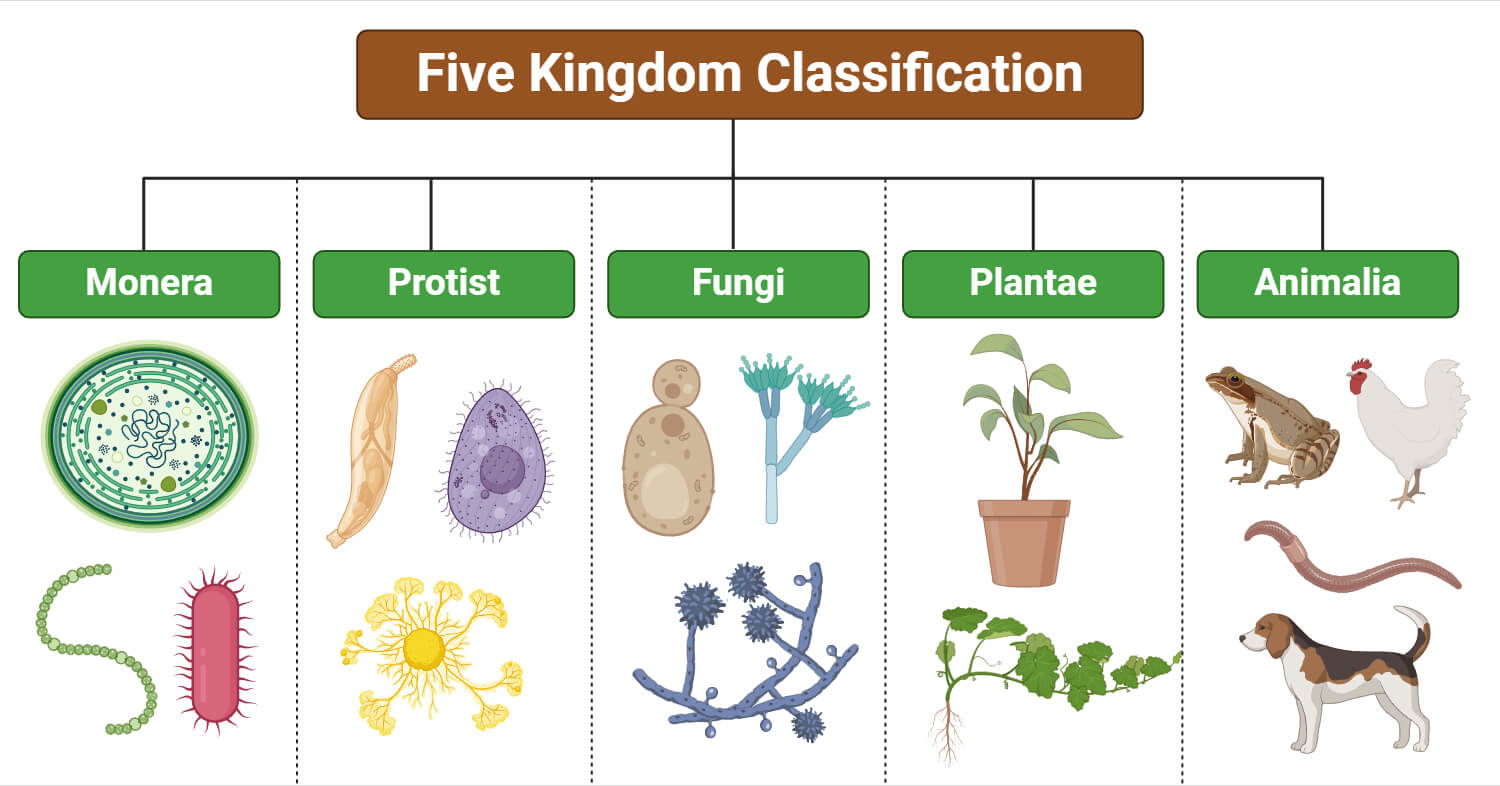

Fungi, distinguishing themselves within the eukaryotic kingdom through intricate cellular structures and diverse biological roles, are among nature’s most sophisticated multicellular life forms. Unlike prokaryotes—simple organisms lacking a defined nucleus—fungi embody the elegance and complexity characteristic of eukaryotic cells, including membrane-bound organelles such as mitochondria and a nucleus housing DNA organized into chromosomes. This cellular sophistication enables fungi to perform critical ecological functions, from decomposing organic matter to forming vital symbiotic relationships.

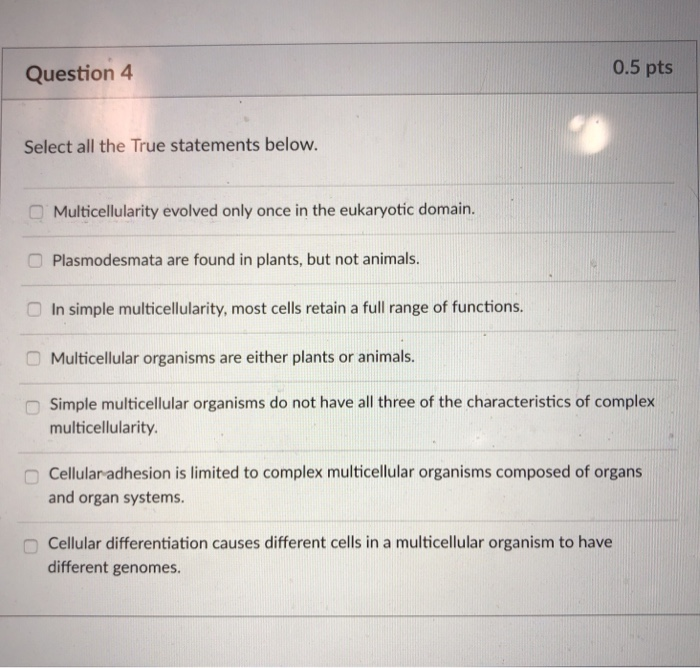

Understanding whether fungi are prokaryotic or eukaryotic is not merely a taxonomic distinction—it reveals profound insights into their biology, evolution, and utility in medicine, industry, and ecology.

The Cellular Architecture of Fungi: Eukaryotic Complexity in Action

Fungi belong unambiguously to the eukaryotic domain, a classification grounded in fundamental cellular architecture. Their cells possess a defined nucleus enclosed by a double membrane, along with well-organized organelles responsible for energy production, nutrient synthesis, and waste management.The mitochondria drive ATP synthesis through aerobic respiration, while the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus facilitate protein and lipid processing and trafficking. Unlike prokaryotic cells, which lack these compartmentalized structures, the presence of such organelles enables fungi to regulate complex biochemical pathways and respond dynamically to environmental cues. A defining eukaryotic feature exhibited by fungi is meiosis—the cell division process producing genetically diverse spores.

This reproductive strategy contrasts sharply with prokaryotic binary fission, underscoring fungi’s positioning within a lineage that values genetic variability and adaptability. The development of cell walls rich in chitin—a nitrogen-containing polysaccharide—is another unmistakable eukaryotic trait. Chitin reinforces fungal structure, supports hyphal networks, and plays a key role in pathogenicity and interaction with substrates, distinguishing fungi across ecological niches.

No Nucleus, No Boundaries: Redefining Life at the Eukaryotic Level

One of the most fundamental markers of eukaryotic life is the presence of a membrane-bound nucleus, a defining breakthrough in cellular evolution. Fungal cells fully embrace this design, housing linear chromosomes contained within a nuclear envelope. This structural organization allows for advanced gene regulation, enabling fungi to orchestrate complex developmental processes such as sporulation, hyphal growth, and stress responses.In stark contrast, prokaryotes—whether bacteria or archaea—lack this nuclear boundary, housing genetic material in a nucleoid region without protective membranes. This nuclear integrity enables intricate transcriptional control and RNA processing, empowering fungi to rapidly adapt their metabolism under fluctuating conditions. For instance, when encountering nutrient scarcity, many fungi transition from vegetative hyphal growth to spore formation, a process regulated at the nuclear level.

By contrast, prokaryotic adaptation relies heavily on horizontal gene transfer and rapid mutation, mechanisms that, while effective, lack the nuanced regulation enabled by a centralized nucleus.

From Decomposers to Symbionts: The Ecological Prowess of Eukaryotic Fungi

Fungi’s classification as eukaryotes directly informs their ecological versatility and evolutionary success. Their capacity for aerobic respiration fuels efficient energy extraction from complex organic compounds, positioning them as essential decomposers in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.Through enzymatic breakdown of lignin and cellulose, fungi recycle carbon and nutrients, sustaining soil fertility and driving global biogeochemical cycles. Equally remarkable is their ability to form mutualistic relationships, most famously with plant roots in mycorrhizal associations. In these partnerships, fungal hyphae expand the root system’s reach, enhancing water and mineral uptake—particularly phosphorus and nitrogen—while receiving carbohydrates in return.

This symbiosis exemplifies the高度 integrated physiology made possible by eukaryotic complexity. Unlike prokaryotic interactions, which may range from parasitic to benign, fungal symbioses are tightly regulated, co-evolved partnerships sustained through sophisticated communication and nutrient exchange. Other e katholic eukaryotic innovations further clarify fungi’s ecological dominance.

The development of sexual and asexual reproductive cycles—driven by meiosis—allows genetic recombination, promoting resilience in changing environments. Meanwhile, the formation of specialized structures such as chlamydospores and appressoria enables survival under stress and host penetration, respectively. These features highlight a level of biological sophistication absent in prokaryotes, where adaptation tends toward speed rather than structural refinement.

Their genetic economy favors efficiency over complexity. Fungi, by contrast, represent a pinnacle of eukaryotic specialization—larger, structured, and dependent on intricate developmental programs governed by nuclear control. This difference is evident in their metabolic pathways; while prokaryotes often operate through streamlined, generalized processes, fungi deploy a diverse arsenal of enzymes, sonsyllates, and signaling molecules, enabling precise niche exploitation.

Van Freudenwald’s foundational research on fungal evolution emphasizes that eukaryotic complexity evolved incrementally, with mitochondria’s endosymbiotic origin marking a critical threshold. Fungi inherited this mitochondrial machinery, embedding it deeply into their cellular economy. Their eukaryotic blueprint—complete with organelles, a nucleus, and regulated gene expression—allowed them to occupy ecological roles no prokaryote could.

From decomposers to symbionts, fungi leverage engineered biological complexity to shape ecosystems in ways prokaryotes, despite their ubiquity, cannot replicate. In summary, fungi stand unambiguously within the eukaryotic domain, distinguished by a nucleus, organelles, and complex cellular regulation. This classification underscores their capacity for sophisticated adaptation, symbiotic innovation, and ecological centrality—qualities that place them firmly beyond the prokaryotic realm.

Understanding this distinction enriches not only scientific discourse but also practical applications across medicine, agriculture, and environmental science. Fungi exemplify the elegance and power of eukaryotic life—organisms built not just to survive, but to shape the world around them through intricate design, dynamic relationships, and evolutionary ingenuity. Their classification as eukaryotes is not a technicality—it is a testament to the depth, complexity, and enduring influence of life at this level.

Related Post

Expedite Nyt Crossword: Are You Ready To Unlock Your Full Potential?

Unlocking The Earnings Secrets: How Much Does Love After Lockup Cast Make?

Download American Nation: Decoding the Complex Tapestry of U.S. History Through One Defining Lens