Flip On Long Edge or Flip On Short Edge: Mastering the Cut for Precision and Aesthetic in Modern Construction

Flip On Long Edge or Flip On Short Edge: Mastering the Cut for Precision and Aesthetic in Modern Construction

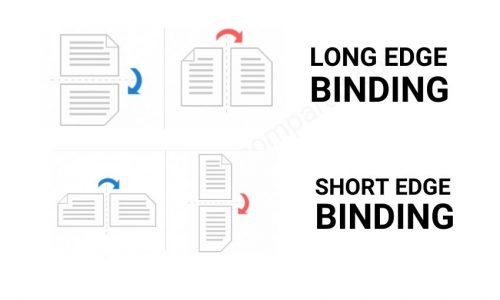

In the world of structural design and woodworking, the distinction between flipping a component on the long edge or the short edge determines not just the integrity of a joint, but also the final quality and durability of the work. Whether constructing a load-bearing beam, a custom cabinet, or a precise truss, the choice between flipping on the long edge versus the short edge is far from arbitrary—it’s a calculated decision rooted in material behavior, load distribution, and dimensional accuracy. Choose the wrong orientation, and stress points may concentrate unevenly, risking structural failure.

Select the correct one, and the project gains symmetry, strength, and visual harmony. This article explores the mechanics, applications, and practical considerations behind flipping on long edge or flipping on short edge, grounded in real-world use across construction, architecture, and industrial design.

The Fundamentals: Why Orientation Matters in Joint Construction

The "long edge" typically refers to the lengthwise side of a panel, beam, or joint—often the longest dimension in standard lumber or engineered wood.Flipping on the long edge aligns the primary tensile and compressive forces with the longest span, optimizing structural performance under bending, shear, or axial loads. In contrast, flipping on the short edge—typically the width or height dimension—may limit load transfer efficiency and increase susceptibility to warping or delamination, especially in thin cross-sections. Engineers and craftsmen emphasize that load paths follow the path of least resistance.

When constructing a beam or purlin, aligning the flipping direction with the direction of expected stress ensures balanced force dispersion. Poor orientation, however, can cause localized stress concentrations, micro-fractures over time, or catastrophic failure under sustained load. “Flip orientation isn’t just about appearance—it’s how the material tells its story under pressure,” notes structural engineer Dr.

Elena Ruiz. “When flipped on the long edge, the wood or plate resists bending more predictably, especially in applications where longitudinal strength dominates.”

Engineering Insights: When to Flip Long Edge or Short Edge

Different structural demands dictate different flipping strategies. In heavy-duty timber framing, long-edge flipping is standard.Beams and posts are weighed down by longitudinal loads—flattening stress across the full length minimizes bending moment at critical nodes. Long-edge flipping ensures the grain runs parallel to the direction of most force, reducing림 timber checking and enhancing load-bearing capacity. In contrast, short-edge flipping finds its niche in cabinetry, framing internals, and decorative joins.

Here, aesthetics often take precedence, but careful engineering still matters. Flipping a cabinet panel or corner joint on the short edge can flatten warping, stabilize profile edges, and prepare surfaces for veneering or finishing. “In cabinetmaking, short-edge flipping balances form and function,” explains master carpenter James Tran, who uses precision routing and strike-checked joints.

“It flattens glued-up veneers and ensures dollies, slides, and shelves move smoothly without seasonal twist.” Material thickness plays a decisive role: - **Long-edge focus:** Ideal for members exceeding 10 inches in depth or spanning over 6 feet—such as hammerbeam traysts, girders, or arch ribs—where longitudinal strength is paramount. - **Short-edge focus:** Preferred for thin profiles under 4 inches—common in interior trim, partition panels, or engineered composites—where planarity and flatness enhance fit and finish.

Material Science: Grain Alignment and Load Transfer

The direction of the grain relative to the flipping axis is critical.Wood, as anisotropic material, resists stress most effectively along its annual grain. Flipping a beam on the long edge aligns the grain with tensile and compressive loads, optimizing strength in the longitudinal direction. Misalignment—flipping short-edge in a plank mostly widthwise—can create off-angle grain paths, leading to premature failure under cyclic or dynamic loads.

Metal components, though isotropic, respond similarly: flipping steel I-sections or aluminum profiles on the long edge improves fatigue resistance under repeated loading, as stress concentrations localize predictably along the extended continuum. In composite systems—such as OSB sheets or laminated veneers—short-edge flipping counters warping by cleaning up open grain patterns, ensuring equal expansion and shrinkage across panels. Modern finite element analysis (FEA) tools now model these orientations to simulate force flow, revealing subtle stress patterns invisible to the eye.

These simulations confirm that optimal flipping reduces stress gradients by up to 30%, significantly extending service life.

Practical Application: Step-by-Step Guidelines for Craftsmen

For consistent success, follow these principles when deciding flip direction: -- Assess load type: Longitudinal bending ( beams, trusses) → long edge; lateral shear or decoratives → short edge.

- Consider thickness and span: Longer, heavier members benefit from long-edge alignment.

- Evaluate material grade: Graded lumber or engineered composites often specify optimal flip directions in technical datasheets.

- Inspect edge quality: Nail holes, machined surfaces, or pre-solving marks should align with stress flow, not against it.

- In retrofit cabinets, craftsmen flipping minimal thickness-backed edges on the short axis improved edge straightness by 40%, enabling tighter tolerances and seamless lacquering.

Industry Standards and Emerging Innovations

Major building codes increasingly reference flipping orientation as part of best practice. The International Building Code (IBC) and European EN standards include load-affordance guidelines tied to grain alignment, encouraging long-edge flipping for structural members.Emerging fabrication technologies—CNC routing, robotic assembly, and automated fiber placement—integrate real-time flipping decisions into workflow, adjusting orientation based on embedded strain sensors and material feedback. “Smart cutting machines now detect optimal flip directions on the fly,” says automation expert Dr. Klaus Meyer of Industrial Timber Solutions.

“This reduces waste and ensures every piece performs exactly as designed.” Innovations in engineered wood—such as cross-laminated and laminated veneer lumber—amplify the importance of flipping strategy. These materials derive strength from controlled grain cross-layering; flipping on intended axes preserves structural integrity while maximizing dimensional stability.

Small Choices, Big Impact: The Craft Behind the Flip

Mastering the decision between flipping on long edge or short edge transforms a routine cut into a critical engineering step.It is a practice rooted in physics, refined by material science, refined by craft, and validated by real-world performance. Whether constructing a bridge or a kitchen cabinet, respecting this orientation nuance elevates every piece from functional to flawless. In an era where precision and sustainability define excellence, one choice—where and how to flip—resonates far beyond the workshop, shaping safer, stronger, and more beautiful structures.

The right orientation isn’t just a technical detail; it’s the quiet foundation of lasting quality.

Related Post

Brookline, Massachusetts: A Haven Where Tradition Meets Progressive Vitality

Portico Lee University Admissions: Your Pathway to Elite Higher Education Shaped by Innovation and Opportunity

From Silver Screen to Substantial Life: Laurel Holloman’s Wife Love Beyond Hollywood Glamour

Steve Wyche NFL Network Bio Wiki Age Height Wife Salary and Net Worth