Factory Life Defined: Tracing Industrial Evolution Through the Lens of Global Factory History

Factory Life Defined: Tracing Industrial Evolution Through the Lens of Global Factory History

From ancient craft workshops to 21st-century smart factories, the concept of factory life has fundamentally shaped human civilization, economy, and society. The factory, in its simplest definition, is a centralized space organized for efficient mass production—yet its historical development reveals a dynamic interplay of technology, labor, culture, and innovation that transcends mere manufacturing. Examining factory life through a global historical lens uncovers how industrial organization evolved across civilizations, responding to economic pressures, technological breakthroughs, and shifting social structures.

In this article, we explore the evolution of factory life from antiquity to the digital age, revealing how these hubs of production not only transformed economies but also redefined human purpose, community, and progress.

The Ancient Roots of Industrial Organization

Long before steam engines and assembly lines, early industrial clusters functioned as primitive incubators of factory-like life. In Mesopotamia and Egypt, temple complexes coordinated specialized artisans producing goods such as textiles, pottery, and tools—elements familiar to modern factory operations.Though lacking mechanization, these centers operated on principles of centralized labor, standardized output, and hierarchical oversight. As historian Arnold Toynbee noted, “The earliest factories were not buildings but social systems—where division of labor and shared purpose gave rise to collective human productivity.” Similarly, in the Indus Valley Civilization (2600–1900 BCE), urban centers like Mohenjo-Daro featured standardized brick production and organized craft workshops, signaling early forms of industrial efficiency. These formations laid conceptual groundwork: centralized workplaces, role specialization, and systematic coordination—all hallmarks of later factory systems.

The Early Modern Shift to Mechanized Production

The true dawn of the modern factory emerged during Europe’s Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, where mechanization fused with deliberate architectural design. The textile industry led the transformation, with landmark inventions such as the spinning jenny, water frame, and power loom accelerating production beyond manual limits. Factories now harnessed water and eventually steam power, enabling centralized hubs where hundreds of machines operated under unified management.British textile mills, exemplified by Richard Arkwright’s Cromford Mill (1771), became prototypes of industrial life. Workers rotated shifts, labor clocks enforced discipline, and output efficiency became paramount—principles later adopted worldwide. As social historian Ashley South observes, “The factory was not merely a building; it was a new social organism—one that reorganized time, space, and human relationships.” This era marked the birth of regimented industrial schedules and hierarchical supervision, redefining labor as a quantifiable commodity rather than artisanal skill.

Factory Systems Across Continents: Adaptation and Resistance

Industrialization spread unevenly, shaped by local economies, colonial dynamics, and cultural contexts. In Japan, the Meiji Restoration (1868) catalyzed rapid modernization, with state-led initiatives establishing textile and steel factories modeled on Western designs but adapted to communal work ethics. Unlike the exploitative labor models in Europe, Japanese factories emphasized group harmony and long-term worker investment, creating a distinct variant of industrial culture.In colonial India, British-owned textile mills exported raw cotton while suppressing local production, transforming traditional artisans into factory workers under coercive conditions. This duality—progress through industrialization versus exploitation under empire—reveals how factory life’s definition was deeply influenced by power, inequality, and resistance. Meanwhile, in the American South, cotton mills powered by slavery became economic engines, embedding factory production into systems of racial subjugation.

These divergent paths underscore that factory life cannot be abstracted from the socio-political environments that shaped it.

Labor Unions and the Fight for Human Dignity

As factories grew, so did worker discontent. By the late 19th century, recurring strikes and social unrest prompted institutional changes.The formation of unions—such as Britain’s Amalgamated Textile Operatives in 1868 and the U.S. Industrial Workers of the World in 1905—marked workers’ organized pushback against exploitation. These movements redefined factory life by advocating for shorter hours, fair wages, safety standards, and dignity.

Labor historian David Montgomery explains, “Unions transformed the factory from a site of unchecked authority into a arena of negotiation—where human rights began to shape industrial practice.” Legal reforms followed: the Factory Acts in Britain (1833, 1847), limiting child labor and mandating schooling, and later global labor codes establishing minimum protections. These changes reflect a critical evolution: factory life was no longer dictated solely by capital but increasingly constrained by social justice imperatives.

The Global Surge: Factory Industrialization in the 20th Century

The 20th century witnessed a seismic shift as factory production expanded into every continent, driven by wartime demands and postwar development agendas.The U.S. “Arsenal of Democracy” during World War II epitomized mass industrial mobilization, with factories retooled overnight to produce tanks, planes, and munitions. This era cemented the factory as a pillar of national resilience and global economic power.

In the Soviet Union, state-planned Five-Year Plans centralized factory production to fuel rapid industrialization, prioritizing heavy industry over consumer goods—a model that shaped Eastern bloc economies for decades. Meanwhile, Japan’s postwar recovery focused on precision manufacturing and labor discipline, giving rise to globally competitive firms like Toyota, whose real innovation lay in integrating workers into continuous improvement (kaizen). Decolonizing nations during the mid-20th century faced a paradox: adopting factory systems to build economies while avoiding replication of Western exploitative models.

Countries like India experimented with mixed public-private models, while others embraced export-oriented industrial parks, blending global standards with local needs. These varied experiments illustrate how factory life adapted to diverse political and economic visions.

Automation and the Digital Factory Revolution

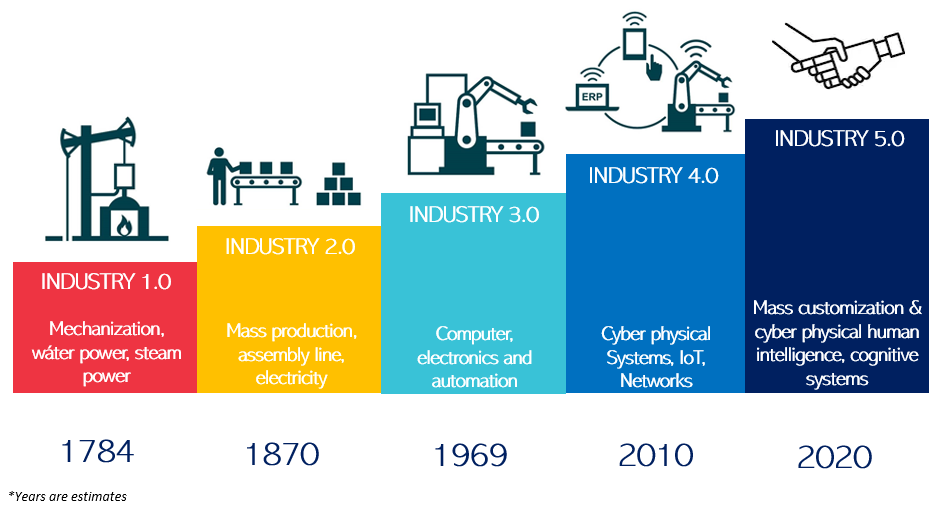

The late 20th and early 21st centuries introduced a transformative shift: digitalization and automation.Robotics, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things (IoT) redefined production floors. Smart factories now self-optimize through real-time data, predictive maintenance, and machine-to-machine communication. Germany’s Industry 4.0 initiative, launched in 2011, exemplifies this trend—focusing on interconnectivity, flexibility, and human-machine collaboration.

Yet automation brings complexity. While productivity surges, the nature of work evolves: skills shift toward programming, data analysis, and creative problem-solving. UNESCO warns that widespread automation risks displacing low-skilled workers without parallel investment in education and reskilling.

Equally, smart factories raise ethical questions about surveillance, data privacy, and algorithmic bias—challenges absent in earlier industrial phases. Despite these tensions, digital tools promise unprecedented efficiency. Tesla’s Gigafactories, for instance, leverage automation not only to scale production but also to ensure quality control and sustainability.

The factory of today, then, is no longer a static assembly line but a dynamic, adaptive ecosystem at the heart of Industry 4.0.

Factory Life Today: Beyond Manufacturing, Toward Sustainable Innovation

Contemporary factory life integrates environmental and social responsibility into core operations. Green factories reduce carbon footprints through renewable energy, closed-loop material cycles, and energy-efficient technologies.Circular economy principles drive factories to reuse, repair, and recycle, minimizing waste. Meanwhile, ethical labor standards—audited by third parties and supported by global certifications—ensure workers’ rights, fair wages, and safe conditions. Consumers increasingly demand transparency: blockchain tracking, for example, allows shoppers to verify a product’s origin and production ethics.

Companies like Patagonia and Fairphone exemplify this shift—using factories not just as production sites but as platforms for social and ecological change. As industrial sociologist Peter Block asserts, “The modern factory must serve not only markets but also the communities it touches—rebuilding trust through accountability.” This broader definition—factories as centers of innovation, sustainability, and ethical engagement—reflects a holistic evolution from past industrial models.

The Future: Human-Centric Factory Ecosystems

Looking ahead, factory life will continue to evolve, shaped by emerging technologies and shifting societal values.Human-robot collaboration, or cobotics, promises to enhance rather than replace human roles—workers becoming supervisors, technicians, and innovators within integrated systems. Decentralized micro-factories, powered by AI and 3D printing, could enable localized, on-demand production, reducing global supply chain vulnerabilities. Society’s growing emphasis on equity will pressure factories to adopt inclusive hiring, living wages, and accessible work environments.

The most resilient factories will balance technological advancement with human dignity—ensuring that progress uplifts both economies and communities. In tracing factory life from ancient workshops to AI-driven hubs, one truth endure: the factory is more than a building. It is a living institution, evolving with each era’s challenges and ideals, forever shaping the story of human civilization.

Related Post

New Examination: Smart Broke Dumb Rich By Zor Veyl Explored

Lyle Trachtenberg Movies Wikipedia Net Worth and Whoopi Goldberg

Serita Jakes Author Bio Wiki Husband Twins and Net Worth

The Controversy Of Coaching & Gambling: When Mentorship Meets Money