Examples of Physical Changes in Food: From Freeze-Fry to Fermentation

Examples of Physical Changes in Food: From Freeze-Fry to Fermentation

From the sizzle of seared peas to the porous crunch of a well-baked bread, physical changes in food transform ingredients at the molecular and structural level—without altering their chemical identity. These transformations, driven by heat, moisture, pressure, or time, reshape texture, appearance, and functionality, turning raw ingredients into the diverse, sensory-rich meals we enjoy daily. Understanding these changes reveals the precise science between kitchen techniques and culinary mastery.

Food undergoes a spectrum of physical transformations during preparation and processing—changes visible to the eye and measurable by microscope. These alterations often determine the final product’s texture, stability, and mouthfeel, playing crucial roles from home kitchens to industrial food production. The contrast between uncooked and cooked states, for example, extends far beyond simple warming: it involves complex molecular rearrangements that unlock flavor, enhance structure, and affect digestibility.

This article explores key examples of physical changes in food, emphasizing real-world applications and scientific mechanisms behind everyday cooking phenomena.

The Maillard Reaction: Beyond Browning—A Symphony of Flavor and Color

One of the most celebrated physical and chemical transformations in food is the Maillard reaction—a non-enzymatic browning occurring when proteins and reducing sugars react under heat, typically above 140°C (284°F). Unlike caramelization, which involves only sugars, the Maillard reaction triggers a cascade of molecular rearrangements that generate hundreds of new flavor compounds, aromas, and brown pigments. This reaction underpins the rich crusts of seared steak, golden-brown loaves, and perfectly roasted coffee.- The Maillard reaction begins when amino acids in proteins interact with reducing sugars like glucose and fructose, forming intermediate compounds that evolve into melanoidins—brown pigments responsible for that appetizing golden hue.

- Because Maillard reactions occur gradually with controlled heat, they exemplify how gradual temperature management shapes texture and taste. A well-cooked steak develops a crisp exterior without burning, whereas overcooking creates char without desirable flavor development.

- In baking, the Maillard reaction influences crust integrity: bread crusts are not just baked—they are chemically rearranged, creating a firm yet tender structure that enhances texture and shelf life.

Scientists describe this process as fundamental to sensory appeal, with flavor chemist Dr. Nicholas Kurti noting, “The Maillard reaction is the poetry of cooking—where heat and time collaborate to turn simple ingredients into gastronomic masterpieces.”

Moisture Removal: Freeze-Drying and Dehydration in Action

Water content profoundly affects food texture, shelf life, and microbial stability.Removing moisture through drying or freeze-drying induces dramatic physical shifts, concentrating flavors and preserving perishables for months or years. Freeze-drying, or lyophilization, preserves cellular structure by freezing food and sublimating ice under low pressure, avoiding liquid-to-vapor collapse that damages tissue.

- Structural Collapse: As water evaporates, capillary forces shrink cells, altering porosity.

Dehydrated fruits become chewy, not soggy, and can rehydrate partially when needed.

- Texture Transformation: Bread slices become brittle; herbs lose fresh crispness but gain lasting potency as oils concentrate. In meat, jerky develops a leathery, elastic firmness.

- Thermal Stability: With moisture removed, metabolism halts—microbial growth and enzymatic spoilage are inhibited, making preserved foods safer for long-term storage.

Industrial freeze-drying, widely adopted in space food and medical supplies, preserves nutritional content and sensory qualities far better than traditional air drying. NASA relies on this process to deliver rehydratable meals for astronauts, maintaining texture and flavor critical for prolonged missions.

Gelatinization: The Science of Cooked Carbs and Starches

Starch, a polysaccharide found in grains, tubers, and legumes, undergoes a radical physical transformation when heated in water—gelatinization.Unlike chemical digestion, this process involves water penetration into starch granules, causing them to swell and burst, releasing amylose and amylopectin. The result is a thickened, viscous texture critical for sauces, gravies, and baked goods.

The transformation passes through distinct phases: - Initial granule swelling upon heating below 50°C - Applications of shear that rupture structures above 60°C - Complete dissolution and viscosity increase at 70–80°C

Examples: - Cornstarch mixed in boiling water thickens soups through hydrogen bond reorganization and crystalline disruption. - In risotto, gradual starch release during cooking builds body and silkiness, transforming a liquid into a rich, cohesive mass.- Jellies set when agar or gelatin interacts with water, relying on molecular reconfiguration to form three-dimensional networks that trap liquid.

Food scientists emphasize gelatinization as essential—without it, sauces remain runny, and batters lack structure. Precision in temperature and hydration determines culinary success, from perfect risotto to smooth puddings.

Emulsification and Phase Separation: Stability Through Texture

Many condiments—mayonnaise, vinaigrettes, and custards—depend on emulsions: mixtures of oil and water stabilized by emulsifiers like egg yolks or mustard. Physical changes during emulsion formation and breakdown determine texture and shelf-life stability.In commercial kitchens, maintaining emulsion integrity requires careful control—heat, acid, and mechanical action all influence phase behavior. A failed mayonnaise emulsion crumbles, not sets, underscoring how physical change governs sensory quality.

Structural Collapse and Re-Crispiness: The Case of Baked Goods

Baked goods exemplify how heat-induced physical changes transform batter into structured, texturally dynamic foods.The baking process triggers expansion—from yeast fermentation to starch gelatinization and protein denaturation—culminating in golden crusts and airy interiors. Key Transformations: - Moisture evaporation creates gradients, forcing steam to push rising dough layers into acoustic, slightly porous networks. - Proteins coagulate, forming a solid matrix that locks in structure while allowing air pockets to contribute lightness.

- Starch gelatinization reinforces cell walls, setting texture before cooling halts expansion.

- Steam pressure in a traditional oven generates stretch and lift, critical for proper rise in bread and biscuits.

- Cooling allows moisture redistribution—surface evaporation thickens the crust while interior retains softness, enhancing mouthfeel.

- Without these changes, baked goods would be dense, gumlike, or collapsed—lacking complexity and appeal.

Artisan bakers leverage this knowledge intuitively, adjusting hydration, oven temperatures, and proofing times to achieve desired crumb structure—from airy sourdough to flaky croissants.

These physical changes—Maillard reactions, moisture removal, gelatinization, emulsion stability, and structural transformation—represent the invisible architecture behind food transformation. Far from passive, they are the deliberate, measurable forces shaping flavor, texture, and function across culinary traditions.

By understanding these processes, cooks and food developers alike unlock the precision to innovate, preserve, and delight. Each bite, from seared film to crispy crust, tells a story written in molecules—where science breathes life into ingredient, and change becomes flavor.

Until the next careful slice or stir, remember: food transforms not just in heat, but at the microscopic level—crafted by physics, shaped by chemistry, and elevated by human understanding.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/TC_608336-examples-of-physical-changes-5aa986371f4e1300371ebebb.png)

/TC_608336-examples-of-physical-changes-5aa986371f4e1300371ebebb.png)

/physical-and-chemical-changes-examples-608338_FINAL-2-69bf88aa2f774afa8bba8df2ec203e70.png)

Related Post

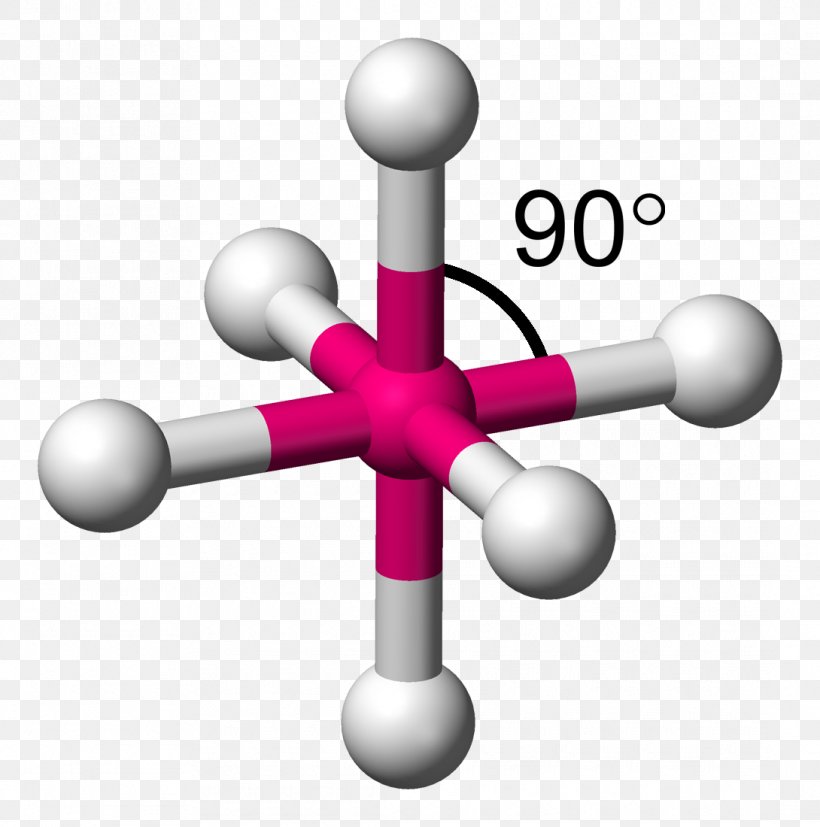

PCl5 Molecular Shape: The Calorie of Chemistry Shaped by Trigonal Bipyramidal Precision

How the Wealthiest Florentine of 1407 Forged a Legacy Built on Trade, Power, and Political Acumen

Surname Explained Everything You Need to Know: Roots, Roots, and the Language Behind Your Last Name

Genesis Trails A Journey Through Daybreak: A Sacred Path Awakens