Define Domain in Math: The Gateway to Unlocking Function Behavior and Real-World Applications

Define Domain in Math: The Gateway to Unlocking Function Behavior and Real-World Applications

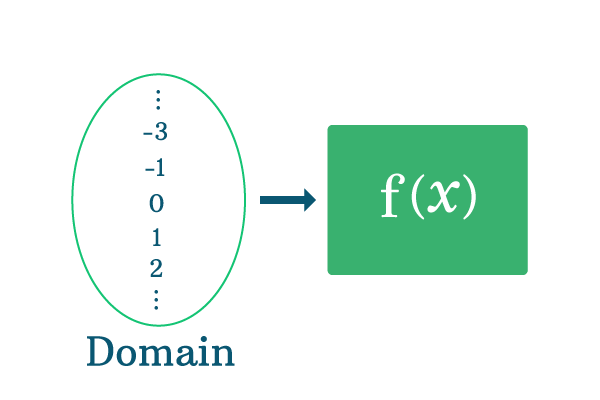

From algebra to calculus, functions shape the language of mathematics—and at the heart of understanding these mathematical mappings stands a foundational concept: the domain. Defining the domain in math means identifying all valid input values for which a function produces meaningful, well-defined outputs. Without a clear domain, even the most elegant function becomes ambiguous, prone to errors, and misinterpreted across scientific and engineering applications.

This precise boundary determines not only mathematical correctness but also the reliability of models used in technology, physics, and economics. Defining the domain goes far beyond listing acceptable numbers; it reflects deeper logical and contextual boundaries that shape how functions behave in reality. Whether analyzing a quadratic model or assessing real-world constraints in data science, understanding the domain ensures mathematical representations align with tangible phenomena.

The Core Definition: What Is a Domain in Mathematical Terms?

In formal mathematics, the domain of a function is the complete set of input values—typically from a specified domain of discourse—along which the function produces real numbers or map-mapped outputs without violating mathematical rules or logical consistency. For a function \( f(x) \), the domain determines the allowable values of \( x \) for which \( f(x) \) remains defined and meaningful. This definition relies on foundational concepts: - The function maps each element of the domain to a unique output in the codomain, usually real numbers.- Domain constraints arise from restrictions such as division by zero, square roots of negative numbers, logarithms of non-positive inputs, or physical laws governing measurable phenomena. - For example, while \( f(x) = \sqrt{x} \) may formally accept all non-negative reals, its practical domain is \( x \geq 0 \)—a critical technical boundary. > “A function is only as reliable as its domain,” observes mathematician Laura Chen.

“Defining the domain precisely is not just a technical habit—it’s the cornerstone of meaningful mathematical modeling.” Defining the domain rigorously prevents undefined behavior and supports consistent analysis across disciplines.

Types of Domain Restrictions and Their Practical Significance

Mathematical domains are shaped by both abstract mathematical rules and real-world constraints. Each type of restriction serves a distinct purpose in preserving validity and relevance: - **Algebraic Restrictions** stem from operations that are undefined for certain inputs: The expression \( \frac{1}{x - 3} \) faces division by zero when \( x = 3 \), so its domain explicitly excludes this value.Similarly, \( \sqrt{x - 5} \) requires \( x \geq 5 \) to keep the radicand non-negative—critical for real number outputs. - **Functional Domain Constraints** come from how functions represent real-world systems. For instance, in physics, velocity is bounded: negative speeds often have physical meaning (e.g., westward motion), but velocity functions model time intervals where input parameters remain valid.

- **Logical and Contextual Boundaries** reflect domain-specific knowledge. A function modeling population density cannot accept negative populations, and temperature models avoid values below absolute zero. These constraints ensure functions behave predictably and produce outputs that interface reliably with measurements, experiments, and technology.

Methods for Defining and Determining Domain in Practice

Mathematicians and scientists employ systematic approaches to identify and formalize a function’s domain. These methods combine analytical reasoning with domain-specific insight. One fundamental step is identifying algebraic limitations.Functions with rational forms require denominators ≠ 0; functions containing logarithms or square roots demand non-negative arguments. For example: For \( f(x) = \frac{\ln(x - 2)}{x + 1} \), the domain intersects two conditions: \( x - 2 > 0 \Rightarrow x > 2 \), and \( x + 1 \neq 0 \Rightarrow x \neq -1 \). Since \( x > 2 \) excludes \( x = -1 \), the domain simplifies to \( x > 2 \).

Visual tools such as graphing software also aid domain determination: asymptotes, discontinuities, and undefined regions become apparent, guiding precise boundary definitions. Contextual knowledge plays a vital role. A function modeling carbon emissions based on temperature must exclude values outside climatic boundaries—such as subzero or vacuum-level temperatures—to reflect physical reality.

This qualitative understanding ensures domains are not purely theoretical, but grounded in observable phenomena. Furthermore, when combining functions—through addition, multiplication, or composition—domain rules intensify: the domain of the composite function is intersections of all component domains. For instance, if \( f(x) = \sqrt{x} \) and \( g(x) = \frac{1}{x} \), their product \( h(x) = f(g(x)) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{x}} \) requires \( \frac{1}{x} \geq 0 \) and \( x \neq 0 \), resulting in domain \( (0, \infty) \).

These techniques transform mathematics from abstract manipulation into precise, actionable design.

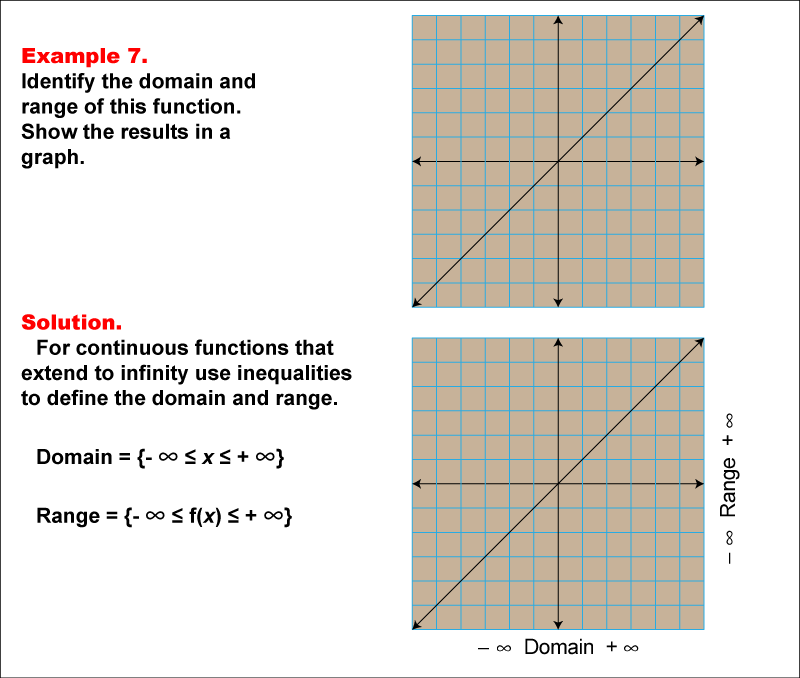

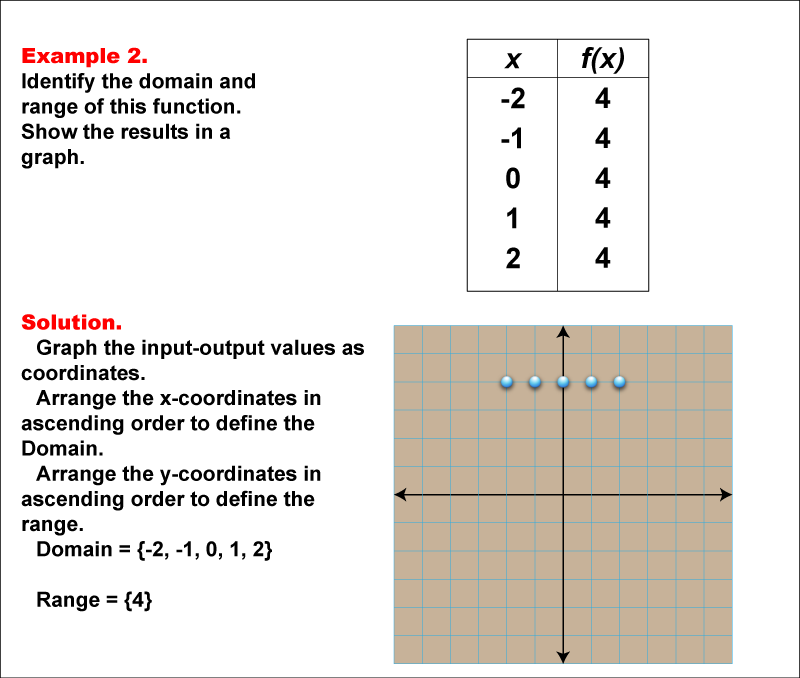

Domain vs. Range: Distinguishing Core Boundaries

Understanding domain as input boundaries clarifies its contrast with range, the set of possible outputs.The domain anchors a function’s identity by defining where it “starts to work,” while the range captures what it “delivers.” For example: - The function \( f(x) = \sqrt{x^2} \) maps inputs \( x \in \mathbb{R} \) to non-negative outputs—so domain is \( \mathbb{R} \), but range is \( [0, \infty) \). - The logarithmic function \( f(x) = \ln(x) \) demands \( x > 0 \) (domain), but yields all real numbers from \( -\infty \) to \( \infty \) (range). Confusing domain and range risks modeling errors—using undefined inputs as outputs or misinterpreting measurable outputs informs flawed decisions in fields such as finance, engineering, and data science.

Experts emphasize this distinction: “Domain is about possibility of input; range is about outputs. Both are essential, but addressing only one compromises function integrity,” notes Dr. Miles Reed, algebraic modeler at the Institute for Applied Mathematics.

This clear separation ensures functions remain logically coherent and functionally transparent across applications.

Real-World Implications and Applications Across Disciplines

Precise domain definition is not confined to theoretical math; its impact ripples across science, engineering, and technology. In environmental modeling, functions tracking pollutant dispersion restrict inputs to physically plausible values—such as wind speeds above zero and distances within a watershed.Ignoring such constraints risks forecasting erroneous outcomes. In machine learning, model features with bounded domains ensure stable training and avoidance of undefined gradients or infinite predictions. In financial risk assessment, functions modeling asset values exclude negative balances or impossible probabilities, sustaining reliable portfolio analysis.

Numerical analysis leverages domain knowledge to refine algorithms—only evaluating within intervals where functions converge. Similarly, control systems depend on domain constraints to prevent unstable inputs that trigger system failures. > “From modeling climate change to deploying autonomous vehicles, the domain shapes trustworthiness,” explains data scientist Elena Font.

“A function valid only under rare conditions fails in practice—domain rigor ensures models hold under use.” These cross-cutting applications underscore domain definition as not merely an academic exercise, but a critical practice underpinning technological reliability and scientific credibility.

Precision in Domain Shapes Accuracy and Trust in Mathematical Systems

Mathematical functions mirror the structures they represent—whether growth, decay, probability, or physical law—and their domains are the boundary stones that define well-defined mappings. Define Domain in Math is more than a technical notation; it is the essential framework ensuring consistency, validity, and meaningful interpretation.By identifying inputs where functions remain stable, predictable, and contextually valid, practitioners build trust across disciplines. From algebra to calculus, from finance to environmental science, domain clarity transforms abstract equations into powerful tools. In an era relying on data and models, the domain stands as both a foundational concept and a safeguard—keeping mathematics precise, relevant, and deeply impactful.

Related Post

Find Tesla Near Me in Minutes: Your Guide to Powering Closer to Home Electric Mobility

Lazio vs. FC Porto: Decoding the Head-to-Head, A Clash of Tactical Giants

Layer Nerv: Slang Edition — What Ssa Slang Urban Dictionary Really Says About Urban Identity

Mia Mover: Revolutionizing Personal Mobility and Sustainable Transportation