Competitive vs. Noncompetitive Inhibition: The Molecular Battleground That Shapes Biochemical Control

Competitive vs. Noncompetitive Inhibition: The Molecular Battleground That Shapes Biochemical Control

At the heart of cellular regulation lies a finely tuned biochemical arms race where enzymes confront inhibitors—molecules that disrupt their catalytic power. Two fundamental mechanisms govern this struggle: competitive inhibition, where analogs vie for the enzyme’s active site, and noncompetitive inhibition, in which inhibitors bind elsewhere, reshaping the enzyme’s structure. Understanding these processes reveals not only the elegance of metabolic control but also the foundation of drug design, industrial biocatalysis, and disease pathology.

By distinguishing how inhibitors interact with enzymes—either blocking substrates directly or altering enzyme geometry—scientists unlock strategies to manipulate biological systems with precision.

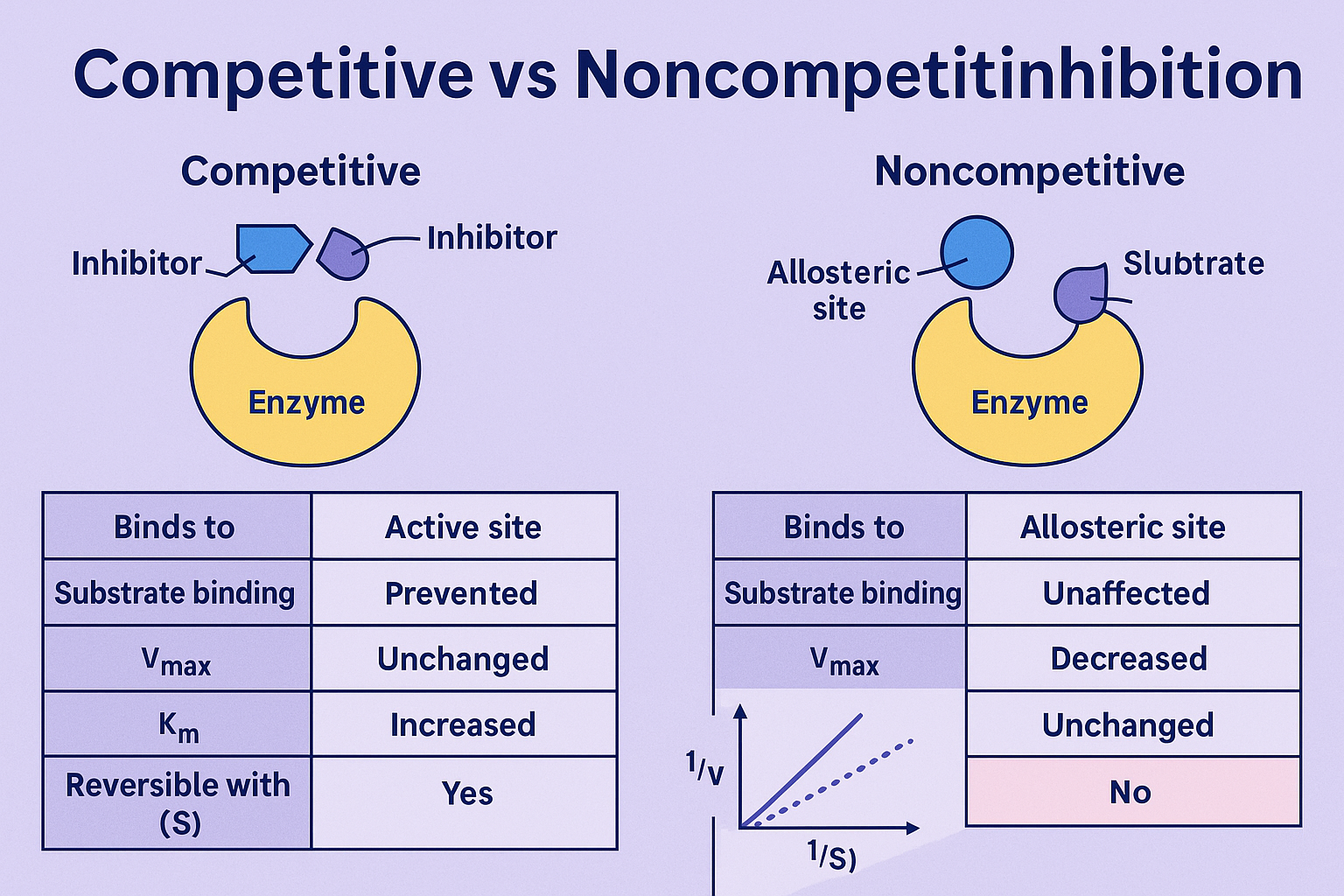

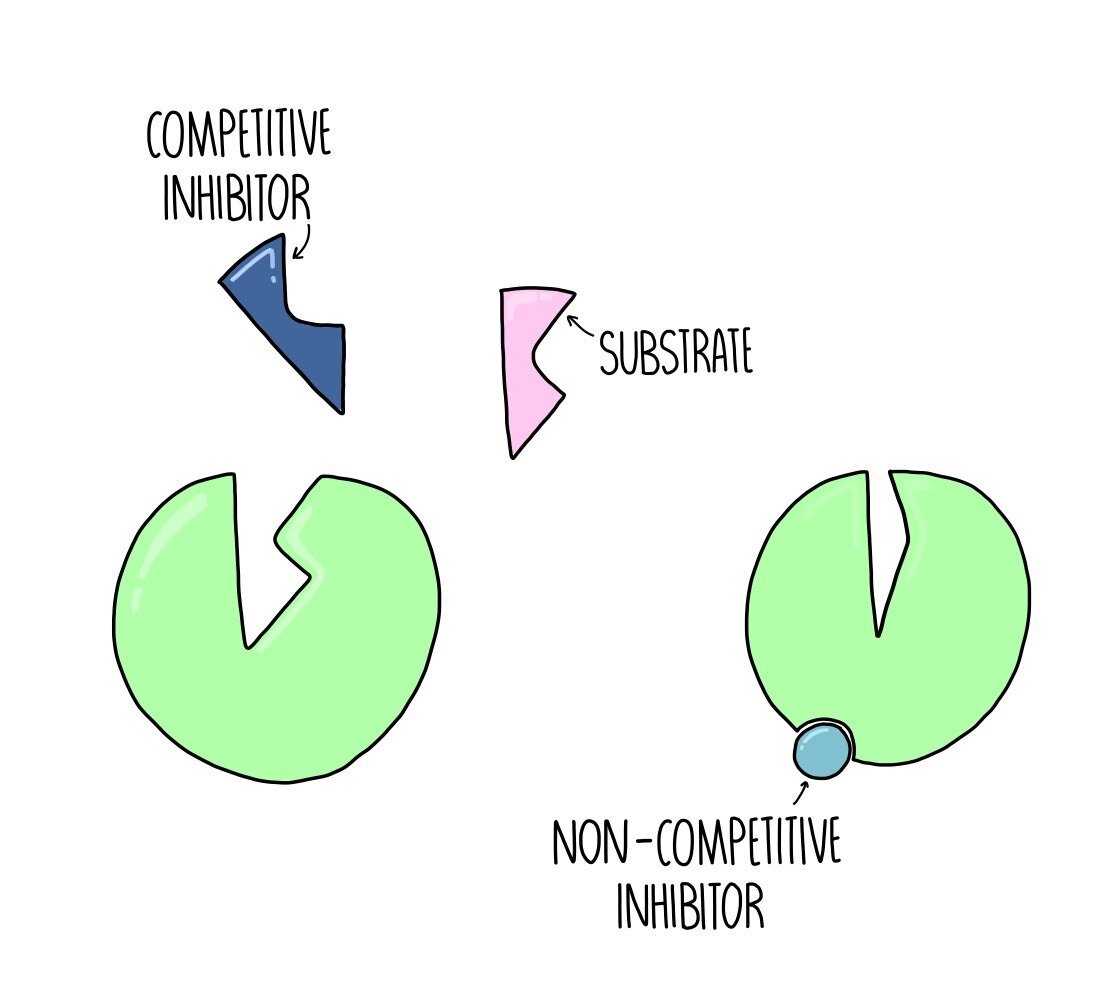

At the molecular level, competitive inhibition manifests when an inhibitor structurally mimics a substrate, binding reversibley to the enzyme’s active site. This mimicry prevents the actual substrate from accessing its binding zone, effectively pausing catalysis until the inhibitor dissociates. “The inhibitor competes with the substrate for access to the catalytic pocket—like two runners contesting the starting line,” explains Dr.

Elena Torres, a biochemist specializing in enzyme kinetics. “Only the stronger bond wins.” This type of inhibition increases the apparent Michaelis constant (Km), meaning higher substrate concentrations are needed to achieve half-maximal reaction velocity, while the maximum velocity (Vmax) remains unchanged. The reversible nature of competitive inhibition makes it a cornerstone in therapeutic strategies, particularly in drug development.

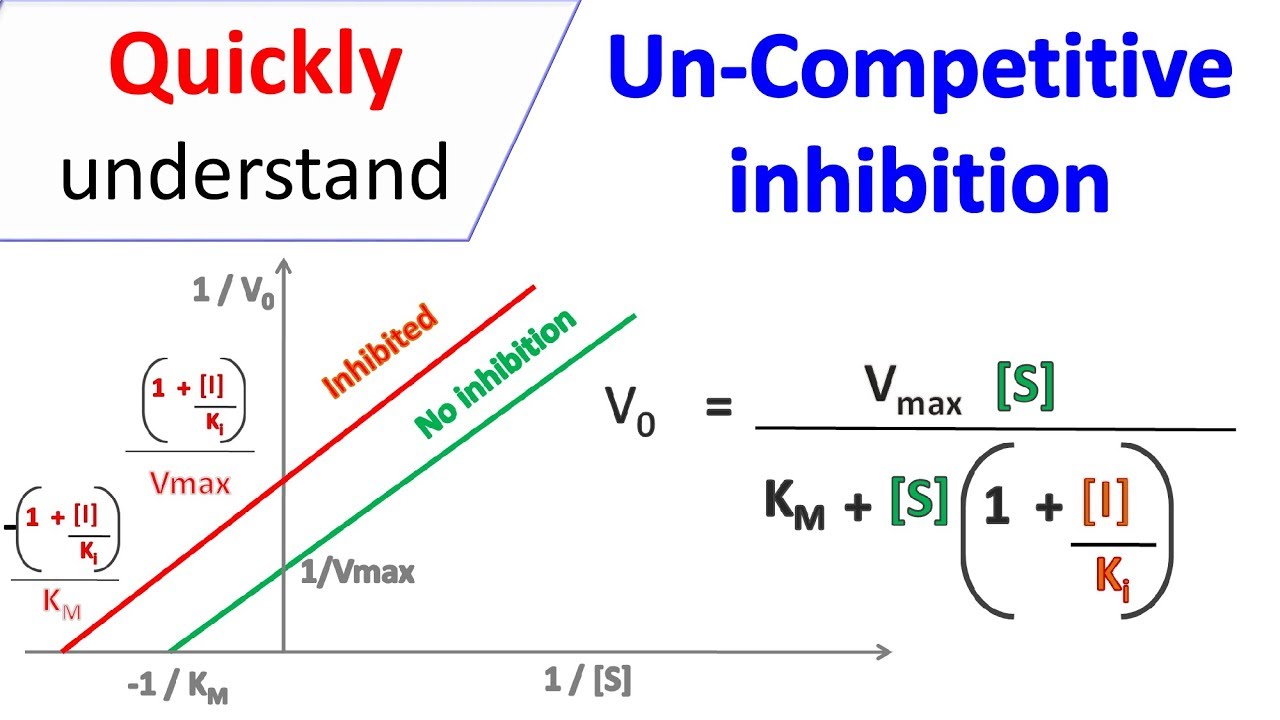

In contrast, noncompetitive inhibition operates through allostery, where the inhibitor binds to a site distant from the active site—often referred to as the regulatory pocket—inducing a conformational shift that reduces catalytic efficiency.

“Noncompetitive inhibitors don’t block the start; they warp the machine,” says Dr. Marco Lin, a structural biologist. “Imagine tightening or loosening gears mid-performance—nobody starts, and when they do, the output weakens.” Unlike competitive inhibition, noncompetitive binding does not alter substrate affinity, meaning Vmax drops while Km stays constant.

This shift reflects a fundamental change in enzyme dynamics, rendering the protein less effective even when substrates are abundant. Such inhibition is critical in regulating metabolic flux and becomes a target in designing allosteric drugs.

The distinction between these inhibition types has profound implications across biology and medicine. Competitive inhibitors are ideal when restoring enzyme function—think statins, which competitively inhibit HMG-CoA reductase, a key enzyme in cholesterol synthesis.

By mimicking the substrate, they lower LDL cholesterol with high specificity. Noncompetitive inhibition, on the other hand, excels in irreversible pathway shutoff—for example, certain antiviral agents bind viral polymerases allosterically, crippling replication permanently. “The choice between blocking availability and crippling performance depends on the goal,” Dr.

Torres notes. “Both mechanisms are essential tools, but their mechanisms dictate their use.”

Understanding the structural and kinetic nuances allows researchers to predict how inhibitors will behave in complex cellular environments. For instance, competitive inhibitors risk reduced efficacy in high substrate conditions; noncompetitive inhibitors remain effective regardless of substrate levels.

This insight shapes dosing regimens and drug combinations, especially in treating diseases rooted in enzyme dysregulation—cancer, metabolic disorders, and neurodegenerative conditions alike. “Enzymes don’t operate in isolation,” explains Dr. Lin.

“The microenvironment—substrate concentration, post-translational modifications, protein partners—morphs the stage for inhibition.” This dynamic interplay underscores why lab findings must be validated in physiologically relevant models.

Real-world applications highlight the power of these concepts. Penicillin, long celebrated for revolutionizing infection treatment, acts as a competitive inhibitor of bacterial transpeptidase, blocking cell wall synthesis. In contrast, heavy metal ions like lead function through noncompetitive inhibition, binding sulfhydryl groups on enzymes and permanently deactivating them—explaining their toxicity.

In biotechnology, mindful inhibition guides the engineering of robust enzymes for industrial catalysis: competitive inhibitors help fine-tune reaction specificity, while noncompetitive modulators stabilize strains under harsh conditions.

Ultimately, competitive and noncompetitive inhibition represent two distinct strategies in nature’s arsenal of biochemical control. One operates at the crossroads of shape and substrate, a lock-and-key duel where access determines victory; the other alters the entire mechanism, reshaping the enzyme’s very nature to undermine function.

Mastery of these pathways empowers scientists not only to decode life’s molecular rhythms but to intervene with surgical precision—whether designing life-saving pharmaceuticals or engineering sustainable industrial processes. The battlefield of inhibition, though microscopic, holds vast potential for discovery and innovation.

Related Post

Lauren Ash Husband: A Visionary Bride in Modern Matrimony

Decoding the Phenomenon: Inside the Kinnporsche Cast and Global Impact