Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy: The Hidden Brain Damage Behind Silent Cognitive Decline

Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy: The Hidden Brain Damage Behind Silent Cognitive Decline

Deep within the brain’s intricate architecture lies a silent but destructive force capable of undermining memory, cognition, and even triggering strokes—Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA). This underestimated neurodegenerative condition involves the abnormal deposition of amyloid-beta protein in the walls of cerebral blood vessels, weakening their structure and increasing susceptibility to hemorrhage. Far from a rare curiosity, CAA now stands at the crossroads of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular pathology, reshaping how clinicians and researchers view brain health.

As scientists with the Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy Uworld initiative continue to unravel its complexities, a clearer, more urgent picture of CAA’s impact emerges—one demanding greater awareness and targeted therapeutic strategies. At the core of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy is the mislocalization of amyloid-beta, a protein normally involved in neural signaling and immune defense. When misplaced in blood vessel walls—particularly in cortical and leptomeningeal arteries—it triggers a cascade of damage.

The amyloid deposits stiffen vessel walls, impairing elasticity and blood flow regulation. Crucially, they compromise the integrity of the blood-brain barrier, allowing harmful molecules and immune cells to infiltrate neural tissue. Over time, weakened vessels are prone to microhemorrhages—tiny, often silent bleeds that accumulate unnoticed.

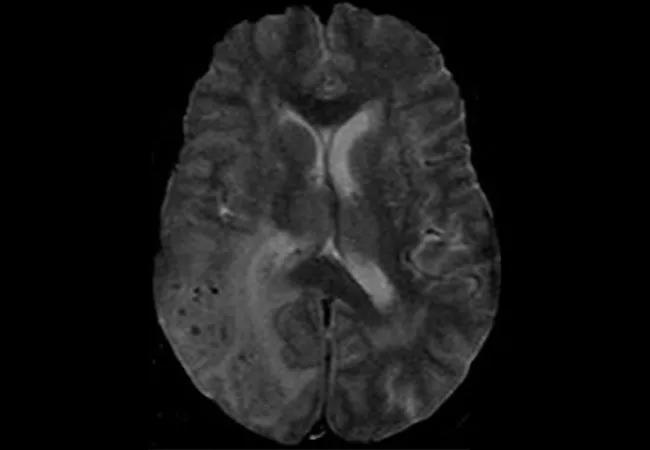

These microbleeds, detectable via advanced neuroimaging, contribute to white matter damage and slow cognitive decline, mimicking but distinct from typical Alzheimer’s patterns.

The clinical presentation of CAA is subtle yet insidious. Unlike acute vascular strokes caused by occluded arteries, CAA-related hemorrhage tends to bleed into the brain’s outer connective layers (leptomeninges) or parenchyma, leading to chronic microbleeding.

Patients may experience subtle memory lapses, cognitive slowing, or even asymptomatic lobar hemorrhages that evade routine stroke evaluation. "Many CAA-related events occur without classic stroke symptoms," notes Dr. Elena Ruiz, a neuropathologist involved in the Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy Uworld research consortium.

"They’re masked by the slow progression of vascular injury, making early diagnosis challenging." Diagnostic advances, powered by Uworld’s collaborative data platforms, now enable clinicians to visualize amyloid burdens through MRI-based techniques like susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) and quantitative T2* mapping. These tools reveal microbleeds and vessel wall abnormalities with unprecedented clarity, shifting diagnostic thresholds and enabling earlier intervention. Yet, standard neurological evaluations often miss CAA, underscoring the critical need for specialized imaging protocols in at-risk populations.

Who is most vulnerable? CAA predominantly affects older adults, with prevalence increasing sharply after age 80. Among these, individuals with Alzheimer’s disease face heightened risk, as amyloid pathology in both neurons and vessels creates a synergistic threat.

However, CAA also manifests independently—so-called "pure" CAA—particularly in non-demented patients. The Uworld database highlights a notable gender bias: women represent approximately 60% of diagnosed CAA cases, a disparity linked to both hormonal influences and vascular risk factors. Hypertension, vascular aging, and genetic factors—such as mutations in the APOE ε4 allele—further amplify susceptibility.

Importantly, CAA is not limited to elderly individuals. Emerging research indicates pathological amyloid deposition in younger patients, suggesting earlier onset and broader population relevance. This challenges long-standing diagnostic paradigms and calls for expanded screening in mid-life cognitive complaints with unexplained vascular features.

Pathophysiologically, CAA’s progression unfolds in stages, each contributing uniquely to neurological harm. The first phase involves amyloid oligomerization within vessel walls, initiating local inflammation. Microglial activation and astrocyte reactivity follow, driving oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction.

By the third stage, stable amyloid plaques form, reinforcing vessel stiffness and increasing perfusion variability. Crucially, the fourth stage—microhemorrhage—marks the acute phase where brain tissue is breached, releasing toxic iron and inflammatory signals that accelerate neurodegeneration. "This sequential destruction turns silent vessel damage into active brain pathology," explains Dr.

Rajiv Mehta, lead investigator in Uworld’s vascular pathology arm. "Understanding these stages informs timing for potential interventions."

Current treatment remains primarily supportive, focusing on mitigating hemorrhage risk and managing symptoms. Anticoagulation therapies, typically used for atrial fibrillation, are contraindicated due to CAA’s bleeding vulnerability.

Instead, blood pressure control via renin-angiotensin system modulators and lifestyle interventions form the cornerstone of prevention. However, the Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy Uworld initiative is accelerating progress toward precision medicine—exploring biomarkers for early detection, vascular-targeted anti-amyloid therapies, and novel imaging endpoints for clinical trials. Yet, challenges persist.

The absence of specific pharmacological agents capable of clearing vessel wall amyloid hinders definitive treatment. Researchers are exploring monoclonal antibodies and small molecules designed to stabilize amyloid deposits, but translation from lab to clinic remains slow. Meanwhile, the wide variability in clinical presentation complicates patient stratification, delaying targeted trials.

Living with CAA demands vigilance. Beyond medical management, individuals at risk benefit from cognitive monitoring, fall prevention (due to unsteadiness), and lifestyle optimization. Emerging data suggest that vascular health—regulated by diet, exercise, and blood pressure control—may directly influence CAA progression.

Patients and clinicians alike are urged to recognize subtle early cues: unexplained falls, sudden memory fog, or unintended speech changes that precede classic dementia signs. CAA’s silent, creeping damage underscores a sobering truth: what breaches the brain’s defenses may lie not just in neurons, but in the very vessels meant to nourish them.

The Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy Uworld consortium is redefining how this condition is understood, diagnosed, and addressed—bridging gaps between neuropathology, radiology, and clinical neurology.

Yet, as the preponderance of CAA grows with an aging global population, so too does the urgency for public health strategies focused on early detection and preventive care. By integrating advanced imaging, molecular biomarkers, and risk modification, the medical community moves closer to turning CAA’s hidden threat into a manageable, if not fully reversible, reality.

Mapping the Risk: Who Faces Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy?

Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy does not affect all brains equally.Several well-documented risk factors elevate susceptibility, shaping who is most likely to develop this insidious pathology. The most significant determinant is advanced age, with CAA prevalence climbing sharply past 80. Beyond senior years, existing neurodegenerative conditions compound risk—especially Alzheimer’s disease, where shared amyloid pathology blurs diagnostic boundaries.

Gender influence is striking: two-thirds of documented cases occur in women, a disparity researchers link to hormonal depletion across menopause and potential vascular fragility. Hypertension, both chronic and early-onset, contributes by accelerating vascular aging and endothelial damage. Diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease further amplify risk through systemic inflammation and microvascular injury.

Genetic profiling reveals additional layers: carriers of the APOE ε4 allele exhibit increased amyloid deposition in brain vessels, though recent findings suggest the APOE ε2 variant may offer protective effects. Familial CAA cases, though rare, confirm hereditary mechanisms involving mutations in genes like APPO and CLU. Together, these patterns paint a nuanced risk landscape, emphasizing the need for personalized screening in high-risk groups.

The Future of Diagnosis and Therapy in CAA

The Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy Uworld initiative is pioneering a new era in detection and treatment. Using advanced MRI techniques, researchers now map amyloid burden with greater precision, enabling earlier identification of at-risk individuals. Blood-based biomarkers—such as plasma amyloid-β42/40 ratios and neurofilament light chains—are emerging as non-invasive tools to complement imaging.Therapeutically, the focus centers on two fronts: stabilization and clearance. Anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies are being tested for their capacity to halt plaque progression without triggering hemorrhage. Concurrently, vessels-targeted antioxidants aim to reduce oxidative stress and restore microvascular integrity.

Yet, clinical translation lags, hindered by ethical complexities and slow progression of vascular pathology. Harnessing big data from Uworld’s global network accelerates biomarker discovery and trial recruitment, shortening the path from research to real-world application. As neurology moves from reactive diagnosis to proactive intervention, CAA stands at the threshold of a transformation—where early detection could become a powerful shield against silent brain damage.

Related Post

142 Meaning In Chat: What Does It Mean When a Guy Says “142”?

As Melhores Músicas Dos Anos 80 E 90: Uma Viagem Nostálgica Através das Ondas Sonoras que Marcaram uma Era

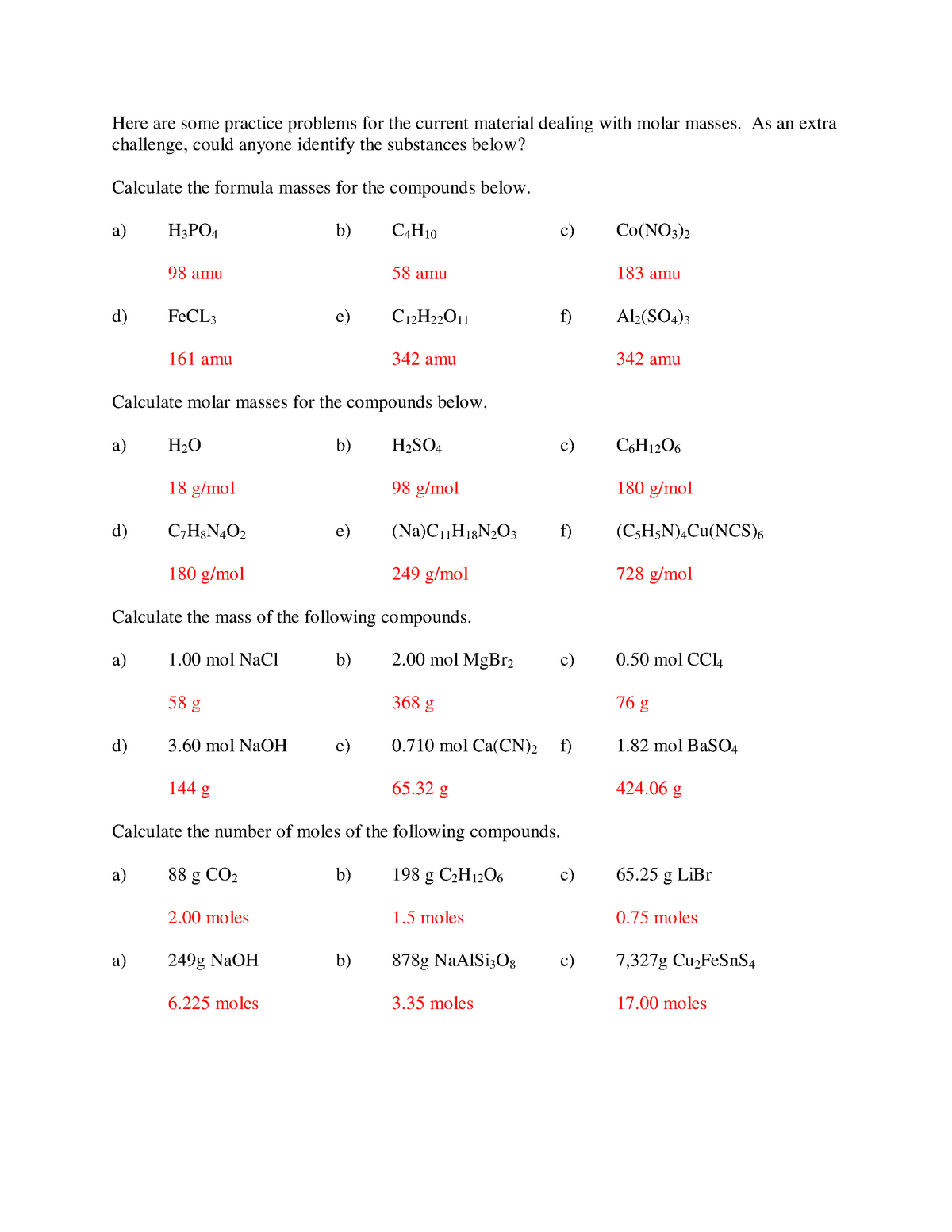

Molar Mass of H₂O: The Cornerstone of Chemistry and Life Itself

The Powerhouse Behind Ryan Cohen: Architect of a Retail Revolution