Are They Really Made In Canada? Decoding the Label on Everyday Products

Are They Really Made In Canada? Decoding the Label on Everyday Products

From groceries to gadgets, consumers worldwide rely on the “Product of Canada” label to guide purchasing decisions—yet the truth behind “Are They Made In Canada?” is more nuanced than the surface suggests. Far more than a patriotic badge, this certification reflects complex manufacturing realities shaped by global supply chains, trade agreements, and evolving definitions of domestic production. While the label inspires trust, how well does it align with actual production practices?

This article explores the criteria, history, impact, and controversies surrounding Canadian-made goods, revealing whether a label can truly reflect a product’s origins in today’s interconnected economy.

The Official Criteria: What Defines “Made in Canada”?

The label “Manufactured in Canada” is not self-declared; it is governed by strict guidelines set by Fisheries and Ocean Canada and Health Canada, and enforced through voluntary certification under the Canadian CCC (Canadian Conformity Certification) system. To earn the designation, a product must meet specific financial and operational thresholds.For manufactured goods, at least 50% of the product’s value—whether labor, materials, or processing—must originate in Canada. Equally important is the requirement that the “substantial transformation” occurs domestically, meaning significant processing, assembly, or manufacturing takes place within Canadian borders. Translation: A maple syrup bottle carried the label only if federal auditors confirmed most of its ingredients, production steps, and final assembly were completed inside Canada.

“Cost is central,” explains Carol Andersen, director of trade policy at the Canadian Trade Commissioner Service. “Full cost includes here, not just final assembly—components sourced elsewhere don’t negate eligibility if processing is done locally.” This technical threshold ensures the label represents genuine Canadian economic contribution, not just branding. Notably, services and digital products face different rules—cybersecurity software, for example, may be “Made in Canada” if development and server infrastructure are fully based here, even if customer support originates abroad.

Still, tangible goods remain the focus, where physical inputs and labor define the score.

Certification Process: From Factory Floor to Label

Acknowledging the label’s significance, manufacturers undergo a rigorous third-party verification process. Companies submit detailed documentation: supplier invoices, payroll records, time-tracking logs, and production workflows.Auditors travel to facilities to observe operations, cross-checking claimed percentages of Canadian value. “An audit might trace a furniture set from maple logs delivered in Ontario, through assembly in a Montreal factory, to final finishing—all before packaging,” notes Kenji Tanaka, a compliance officer with SEMCO Canada, a certification body. “Each stage contributes to the final score.

We validate that 50% or more reflects substantial Canadian economic effort.” Once verified, the certification becomes part of Canada’s Trade Competitiveness Program, assisting exporters in international markets where “Made in Canada” commands premium trust. But flagging a unit as domestic carries reputational weight—breaks in compliance can trigger investigations and de-listing.

Global Supply Chains and the Myth of Domestic Production Modern manufacturing blurs the line between “local” and “global.” Most Canadian-made products rely on an intricate cross-border supply web: raw materials from Australia, machinery from Germany, microchips from South Korea, and components shaped in Mexico.

The question then becomes: where does meaningful transformation occur? Take the iconic Canadian automaker’s vehicle: body panels may come from the U.S., engines from Germany, and electronics co-developed in Japan. Yet assembly in Ontario qualifies as “substantial transformation” under Canadian standards.

“It’s not about 100% origin—it’s about where economic value and labor creation happen,” says Andersen. “We certify that Canadian effort drives the final product’s worth.” Trade agreements further complicate the picture. Under USMCA (formerly NAFTA), goods must meet stringent rules of origin.

For example, a Canadian furniture export to the U.S. requires at least 75% fabric and assembly to qualify as “Made in Canada,” even if lumber comes from U.S. forests.

These rules prevent misrepresentation but don’t eliminate dependency on foreign inputs. Suppliers themselves shape perception. A 2023 survey by Deloitte found that 68% of Canadian consumers view “Made in Canada” as a marker of quality and sustainability, even when products contain imported parts—so long as the narrative emphasizes domestic value creation and oversight.

Sector-Specific Realities: Where Does “Made in Canada” Apply?

Certain industries anchor the label more firmly than others. Maple syrup, progressively certified since the 1970s, remains one of Canada’s most iconic non-mining exports. The Canada Maple Product Association mandates that at least 60% of syrup must be produced and processed in Canada, verified through syrup processing records and sap sourcing compliance.Automotive manufacturing illustrates complexity. Canada’s “Buy-American” policies incentivize domestic content, but final assembly plants often integrate parts from Mexico. Still, the stamp signals Canadian investment—auto assembly lines in Ontario, for instance, support tens of thousands of skilled jobs, qualifying for domestic label status despite global supply routes.

Pharmaceuticals offer another lens. A prescription drug approved and manufactured in Canada qualifies as “Made in Canada,” even if some APIs (active pharmaceutical ingredients) are sourced internationally, provided synthesis and final formulation occur domestically. This meets Health Canada’s safety and accountability standards, reinforcing public trust in pharmaceutical origins.

Electronics reveal tensions. While consumer gadgets often rely on global component sourcing, companies like Bell Canada and BlackBerry emphasize Canadian design, R&D, and manufacturing in labeling decisions—balancing global inputs with domestic innovation credits.

Consumer Perception: The Psychological Power of “Made in Canada”

Beyond codified rules, the label taps into deep-seated consumer values.A 2022 Nielsen report found 74% of Canadian buyers consider “Made in Canada” a top factor in purchasing decisions, citing trust, quality, and national pride. The label signals adherence to strict labor and environmental standards—though not legally mandated, many Canadian producers voluntarily uphold higher benchmarks. “Consumers aren’t just buying a product; they’re buying a story,” observes Tanaka.

“That story includes étmeno local jobs, responsible sourcing, and accountability. When verified, ‘Made in Canada’ becomes a mark of reliability.” Yet skepticism persists. Some consumers question whether certifications are strict enough or suffer from greenwashing.

Experts stress transparency: detailed public documentation and traceable supply chains remain key to

Related Post

Donald Trump in 1998: The Emerging Force Shaping American Ambition and Controversy

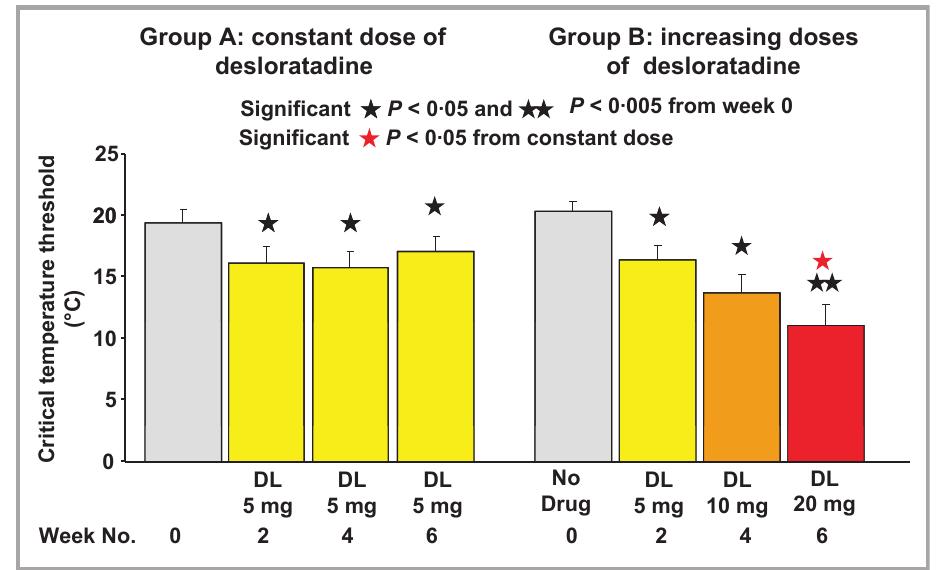

From 37.5°C to 99.5°F: The Science Behind a Critical Temperature Threshold

Freaky Shit To Say: Uncovering The Weirdest Phrases That Will Leave You Stunned

Parker Yeager Age Bio Wiki Height Net Worth Relationship 2023